Making Pictures of the Animals We Eat

Food is a basic human need. In our Food for Thought series, James Beard Award–winning journalist, scholar, and writer Cynthia Greenlee hosts a gathering of historians, food journalists, poets, chefs, and farmers and invites them to riff on food-related works of art in our permanent collection.

As a chef, farmer, and hunter, I often find myself in the company of freshly killed animals. On our West Virginia farm, Amy and I raise chickens and between four and several dozen meat rabbits, depending on the breeding schedule. We find joy in witnessing new life emerge, but it can be devastating to watch lives end, especially as the result of our own actions.

For our rabbits, that time comes at 90 days or so, when they weigh about five pounds. Amy, who has cared for them since they were tiny kits, whispers soft condolences. She tries her best to lend comfort as she carries them one at a time to a small, grassy corral. A few minutes later, the rabbits are calm and mostly unsuspecting. I hover above with a .22-caliber rifle, take a deep breath, and say something like, “Thanks, little buddy,” before placing a close-range shot to the back of the skull.

Killing is but one step on a long, emotional journey behind every skillet of fried rabbit and every plate of rabbit liver toast shared at our table. Some tell me you get hardened to killing, but I hope I don’t. I hope my finger always grasps that trigger with at least some discomfort.

For generations, a small herd of Hereford cattle has roamed the meadows of Lost Creek Farm in north-central West Virginia. Photo by Mike Costello

For generations, a small herd of Hereford cattle has roamed the meadows of Lost Creek Farm in north-central West Virginia. Photo by Mike Costello

Stories of Ceremony and Sacrifice, Told through Images

As long as we choose to consume animals, this intimate grapple with the full circle of life feels important. And since words never seem to capture the harsh, complex realities of putting meat on the table, I capture images as often as I can. Images tell stories; they inspire us to remember what’s important.

I’ve stood by, camera in hand, during unforgettable, gut-wrenching moments as friends and neighbors killed for food: when Seth drained the blood of a young bull, so John’s family could make traditional Spanish blood sausage; when Mehmet prayed over the final breaths of a lamb; when Jonathan ran his fingers through the fur of the first deer he ever harvested, saying, “Thank you for your life. We’re going to do right by it. I can promise you that.”

I mostly keep these images to myself—at least the most graphic ones—because sharing them hasn’t always gone over well. Despite our lust for meat in the United States (which routinely tops the world in meat consumed per person), most folks would rather ignore what it takes to get animal parts to their kitchens. It only takes a few minutes for pictures of compassionate farmers holding severed hindquarters to be flagged for violating content standards on social media.

That’s a shame because, beyond the spattered blood and open carcasses, my images capture respect for culture, heritage, ceremony, and sacrifice. They contrast pride in self-sufficiency and the mourning of lives taken so we can eat well.

Willem van Aelst: Dead Game as Trophies

Still Life with Dead Game seemed familiar, even relatable, when I first saw it. “What was his experience?” I wonder about Dutch painter Willem van Aelst. I speculate that he was a hunter and wanted to convey a deeply personal relationship between himself, the predator, and these animals, his prey. I make these assumptions because similar pictures help me translate my experiences—and those of others. But Van Aelst’s painting lacks graphic detail and does not show the human actor who killed these creatures. Did he consider the same themes: ceremony, sacrifice, grief?

When I notice the description of the animals as “trophies” on display, I’m reminded of stark differences between killing for survival and killing for sport. According to the painting’s accompanying text, Still Life with Dead Game was part of a genre that “appealed to the aristocratic aspirations” that were common “at a time when Dutch society grew wealthier and more refined.” Of course. The rich love showing off collections of dead things to contrast conquerors against the conquered. This reminds us who’s in charge and who has the money, the access to land, and the leisure time to kill simply for fun.

Hunting for Sport Versus Sustenance

The hunters I grew up with killed for sustenance, but also mostly enjoyed hunting as a pastime. So at the time, I didn’t notice the conflict between survival and sport.

A younger me would have wondered why those who commissioned a work by Van Aelst didn’t prefer to see the animals painted in their liveliest state. But as I grew up, I heard stories that made heroes out of those who felled the tallest old-growth trees, shot the most wolves, or killed the last buffalo in West Virginia. Settlers were respected for collecting impressive dead things—trophies—in the name of taming the Appalachian frontier. I eventually understood that there’s little room for living, breathing bodies in tales of colonialist settlers conquering the natural world.

When dead animals are put on display, so are class and economic status. Viewers may interpret images of hunting and farming—especially the bloody, gritty details of the kill—as criticism of those they consider poor enough to have to kill to survive. But the same viewers may use sanitized displays of dead carcasses—whether taxidermied mounts or 17th-century paintings—to celebrate those who are well-off enough get to kill for sport. This was all on my mind again in autumn as deer season arrived in West Virginia and my Instagram feed became its own version of Still Life with Dead Game, just as it does every year.

Each fall, I see hundreds of pictures of dead deer, often accompanied by proud accounts of canning stew meat, curing venison bologna, and freezing deer burgers for the year ahead—the same stories I look forward to sharing myself. But I also hear from rather wealthy folks who—after investing in trendy new hunting clothes, high-tech game cameras, and months’ worth of a growth-enhancing deer feed called something like “AntlerMax”—show off their 12-point bucks and complain about the taste of venison.

Sport and sustenance aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive, but there’s some tension between impressive trophies and quality food. Big bucks come with big antlers, but these large, older male animals can be full of testosterone and don’t always produce pleasantly flavored and textured meat. They can still yield delicious meals, but that takes skillful butchery, culinary know-how, and enough patience to properly rest the carcass while intense hormones mellow. You learn all of this when hunting is understood as an act of nourishment, not as an aspirational flex. Spending thousands to showcase trophies doesn’t help anyone stomach gamey burgers and chewy backstraps.

Hunting and farming are time-honored traditions I’m proud to carry forward, and I do so with an eye for images that tell powerful stories. I’ll always look for hunting-season or slaughter-day pictures that remind me of conflicted emotions and show animals as more than just trophies. That’s what I first saw in Still Life with Dead Game—at least it’s what I hope Van Aelst’s painting can represent.

You may also like

Article: Introducing the Food for Thought Series

In this series, chefs, farmers, historians, scholars, and other thinkers share their takes on food, consumption, cooking, and eating.

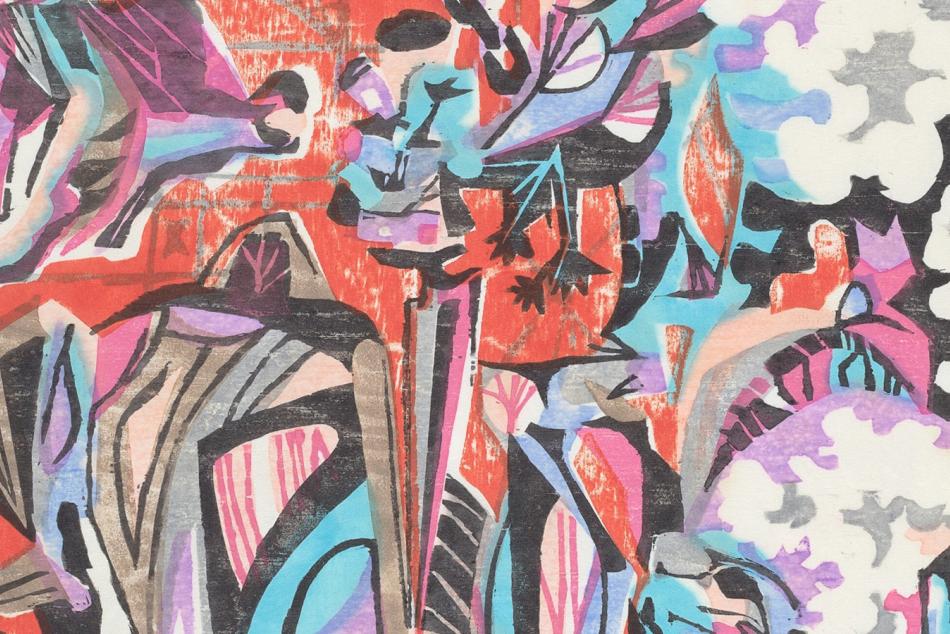

Article: Eldzier Cortor Takes Us Inside the Slaughterhouse

Through his surrealist woodcut, Cortor considers the relationship between humans and animals and tells the stories of Black bodies.