Who Is Philip Guston? 10 Things to Know

Why do his paintings remain so urgent and relevant today?

Philip Guston is among the most influential artists in modern art. We’ve gathered key facts about the artist to help you understand his life and work.

Philip Guston, Painting, Smoking, Eating, 1973, oil on canvas, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, © The Estate of Philip Guston

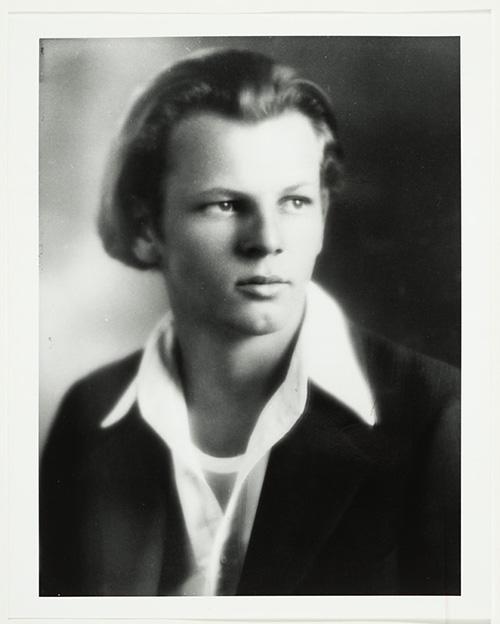

1. He was born Phillip Goldstein.

Guston was born in Montreal, Canada, in 1913. His Jewish parents had fled persecution in Ukraine nearly 10 years earlier. A few months before his ninth birthday, the family moved to Los Angeles, California.

By 1935, he went by Guston instead of Goldstein, possibly because he thought his girlfriend’s parents wouldn’t accept a Jewish boyfriend.

Guston (left), his mother, Rachel Goldstein, his brothers Nat and Irving, and his sister Rose, Los Angeles, c. 1922

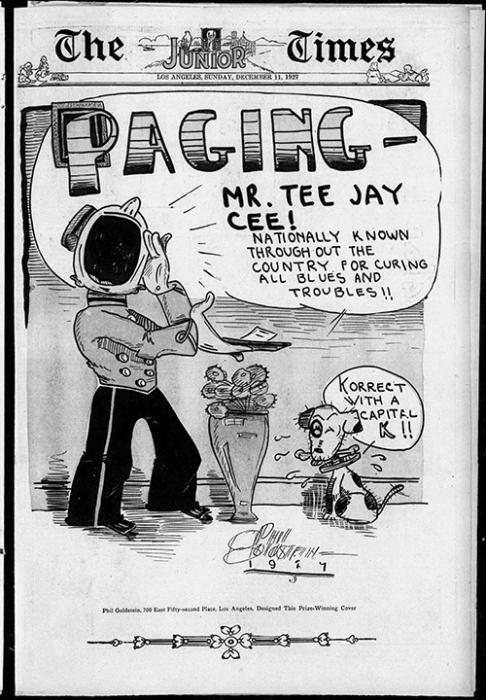

2. He loved comics.

From a young age Guston was interested in art. He started with drawing and was inspired by cartoons like George Herriman’s Krazy Kat and Bud Fisher’s Mutt and Jeff. On his 13th birthday, he had a cartoon published in the kids’ section of the Los Angeles Times. His junior high school yearbook listed him as a “true artist.”

Prize-winning cartoon by Guston on the cover of the “Junior Times,” Los Angeles, December 11, 1927

3. He was friends with Jackson Pollock in high school.

While attending Manual Arts High School in Los Angeles, Guston became friends with Jackson Pollock. The two budding artists remained friends for decades, and Guston moved to New York in 1936 at Pollock’s encouragement.

Soon after Pollock began to make his first “poured” paintings in 1947, Guston embraced abstraction. They became two of the most famous abstract painters working in the 1950s.

4. He studied Renaissance painting.

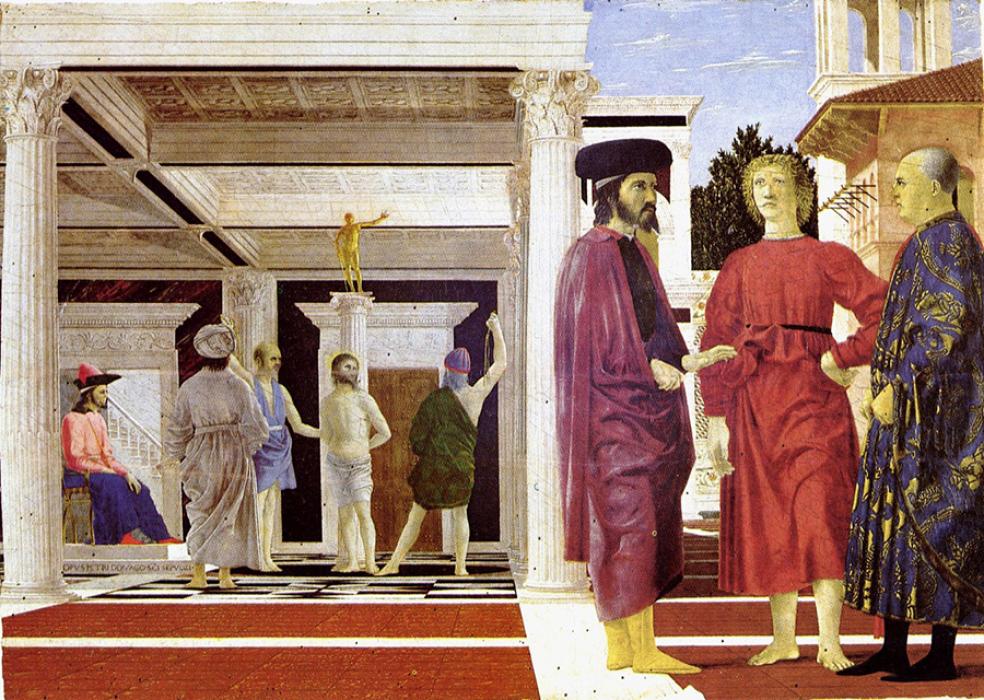

Studying those who came before him was an important part of Guston’s development as an artist. His works may look modern, but Italian Renaissance painters, especially Piero della Francesca, inspired him.

Guston wrote admiringly about the 15th-century artist and hung two reproductions of Piero’s paintings in his studio.

Piero della Francesca, The Flagellation of Christ, 1460, oil and tempera on panel, Galleria Nazionale delle Marche

5. He started out making murals.

As a young artist, Guston made several murals. Living in Los Angeles, he knew the work of some of the most famous muralists at the time—Mexican artists José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros. He may have even helped Siquieros paint one mural.

In 1932 Guston painted a mural of a Black man being whipped by a Ku Klux Klansman as part of a larger series on racism in America, which he was making with friends in the John Reed Club, a local outpost of a network of Communist clubs. Several months later, the Los Angeles Police Department’s Red Squad, a unit that went after Communists, destroyed the murals. Some Los Angeles police officers were known to be members of the Ku Klux Klan.

Several of Guston’s murals still exist today. One of the largest was made as part of the Federal Art Project for the Wilbur C. Cohen Federal Building in Washington, DC, just blocks from the National Gallery. If you visit Philip Guston Now on April 27, you can see the mural that evening during a special program.

Philip Guston, Reconstruction and the Wellbeing of the Family, 1943, oil on canvas adhered to wood, Commissioned through the Section of Fine Arts, 1934–1943, Fine Arts Collection, U.S. General Services Administration, Photo: David L. Olin, Fellow AIC, Olin Conservation, Inc.

6. He changed his style from figuration to abstraction and back again.

Guston didn’t make art in one style that he refined over time. He experimented with surrealism, an avant-garde movement, practiced by artists like Salvador Dalí, that began in Europe and took inspiration from dreams and the unconscious. Later, he found success with abstraction before returning again to figuration (in which the artist depicts things we recognize).

He often dropped subjects and styles and then revisited them. He constantly pushed himself in new directions and rarely did what was expected of him.

Philip Guston, Passage, 1957-1958, oil on canvas, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Bequest of Caroline Wiess Law, 2004.20, © The Estate of Philip Guston, courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

7. He only sold one work from one of his most important exhibitions.

Speaking of the unexpected, in 1970 Guston presented a new group of paintings in an exhibition at the Marlborough Gallery in New York City. Today, those works are considered some of his most significant contributions to modern art. But when he first showed them, most critics hated them. He even lost some friends over them. Some artists considered him a traitor for leaving behind the New York School style of abstract painting, which Guston had made popular along with artists including Jackson Pollock, Robert Motherwell, and Joan Mitchell.

Why were the works so shocking? Guston’s new paintings were large horizontal canvases reminiscent of movie screens or billboards and filled with objects like books, bricks, and shoes painted in a flat and simplified way. They were completely different from the abstract canvases he had been exhibiting until then.

In some paintings, he revisited a subject from his earlier murals and drawings—the Ku Klux Klan. Painted as bulbous white, hooded figures with two vertical strokes to suggest eye slits, they appear riding in cars, smoking cigars, and even painting at the easel.

Guston considered them self-portraits of a sort, and sometimes depicted the Klansman in the act of painting or looking at paintings. With the upheavals of the 1960s all around him, Guston felt the need to interrogate bigotry and violence in his paintings. He asked, “What would it be like to be evil?”

Philip Guston, Blackboard, 1969, oil on canvas, Private Collection. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth Collection Services, © The Estate of Philip Guston; Digital Image (C) The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

8. He made art in response to the Vietnam War and Holocaust.

From the beginning of his career, Guston made art that spoke to what was happening in the world around him. He created one of his earlier paintings, Bombardment, in response to the April 1937 Fascist bombing of the Spanish town of Guernica.

Art allowed Guston to process the seemingly endless series of cruelties and tragedies he witnessed. After seeing photographs of Nazi concentration camps, he painted haunted faces, body parts, and piles of legs.

In the late 1960s, the Vietnam War compelled Guston to return to a more representational style of painting. He reflected on this shift: “The war, what was happening to America, the brutality of the world. What kind of man am I, sitting at home, reading magazines, going into a frustrated fury about everything—and then going into my studio to adjust a red to a blue? I thought there must be some way I could do something about it.”

9. He made a book of satires of President Richard Nixon.

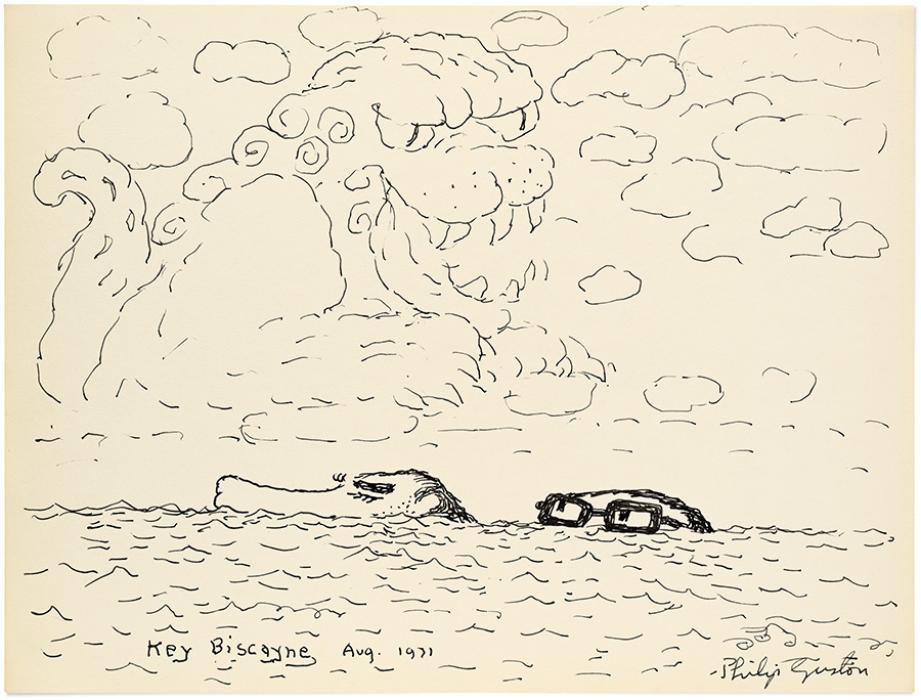

In 1971 Guston read the manuscript of Philip Roth’s novel Our Gang, a satire of President Richard Nixon’s administration. Shortly after, he started a series of caricatures tracing Nixon’s life from youth to presidency.

In total, Guston made 73 drawings of Nixon, Vice President Spiro Agnew, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, and Attorney General John Mitchell for a book. He even designed a title page and named it Poor Richard. But they were not published during his lifetime. The Poor Richard drawings were first shown to the public in 2001.

After the Watergate scandal and Nixon’s resignation, Guston made his only painting of the subject—San Clemente. You can see all these works in our exhibition Philip Guston Now.

Philip Guston, Poor Richard (no. 37), 1971, 1971, ink on paper, framed: 32.39 x 40.96 cm (12 3/4 x 16 1/8 in.), The Guston Foundation, Promised gift to the National Gallery of Art, Washington, © The Estate of Philip Guston, courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

10. He has inspired generations of artists.

Just as Piero della Francesca and Pablo Picasso influenced him, Guston has influenced many of today’s artists. In addition to being done with skill and style, his innovative and provocative paintings remain relevant because of their imaginative freedom and fearless address of social issues. Hear from artists Cecily Brown and Glenn Ligon, along with Guston’s daughter Musa Mayer, about why his paintings stand the test of time.

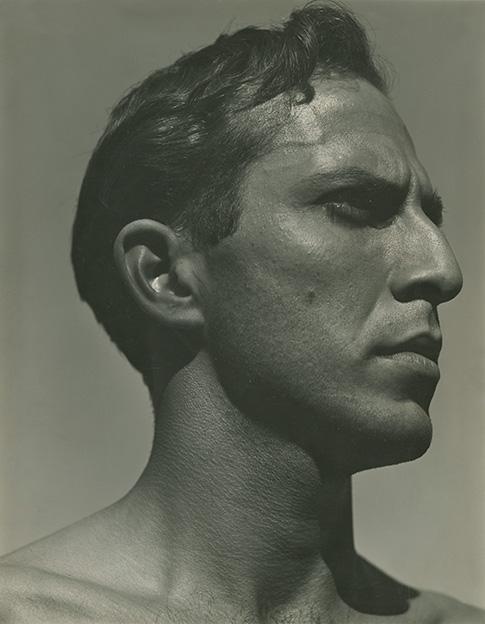

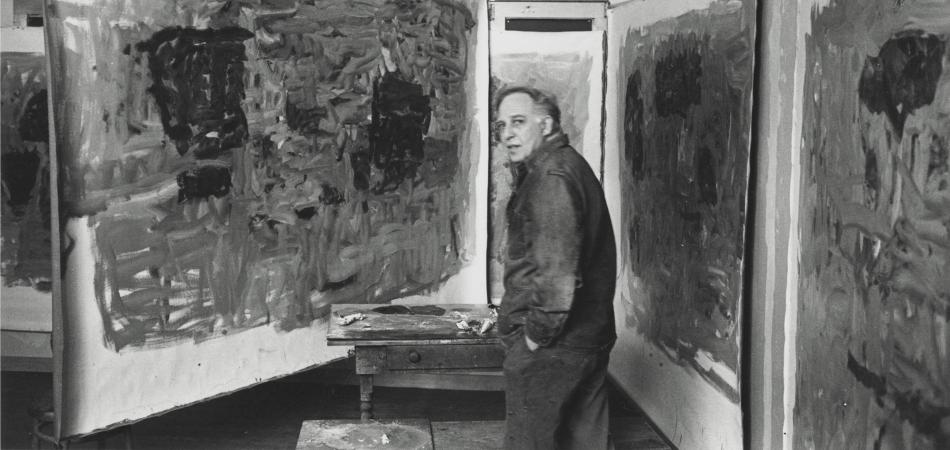

Credit: Guston in his Woodstock studio, surrounded by his gray paintings, 1964, © Dan Budnik, all rights reserved, courtesy of The Guston Foundation

You may also like

Article: George Morrison Gets His Due

The Minnesota painter merged abstract expressionism with traditional Ojibwe values.

Article: Your Tour of Latinx Artists at the National Gallery

Use our guide to explore works by Latinx artists on view in our galleries.