A Poem of Exile on Dante Day

Learn how Dante’s Divine Comedy reflected his desperate desire to return home to Florence, Italy.

March 25 is Dante Day, celebrated as Dantedì in Italy, to honor the timeless achievements of writer/poet Dante Alighieri (1265–1321).

He is considered the father of the modern Italian language because of his famed manuscripts, such as The Divine Comedy (Commedia in Italian), one of the greatest works of European literature. Established in 2020, the celebration falls on March 25, the day Dante begins his fictional journey in The Divine Comedy.

Dante was also a soldier in his early years and always ambitious in the politics of Florence, his birthplace. Tragically, his views landed him on the losing side. His party, the White Guelphs, supported freedom from papal interference in Florentine affairs. The opposing Black Guelphs supported the pope in Rome. After much intrigue and changes of government, the Black Guelphs triumphed.

Accused of corruption and financial wrongdoing, Dante was first exiled from Florence for two years in 1302 after he refused to pay a fine. Shortly thereafter he was banned for life and threatened with execution at the stake or beheading if he returned. Dante refused any pardon that required him to admit guilt against the city he so loved.

For the next 20 years, the poet endured a roving existence, travelling from place to place in Tuscany and other locales at the invitation of friends or fulfilling diplomatic missions at the behest of others. His final years were spent in the city of Ravenna on the Adriatic coast, where he died of malaria in 1321.

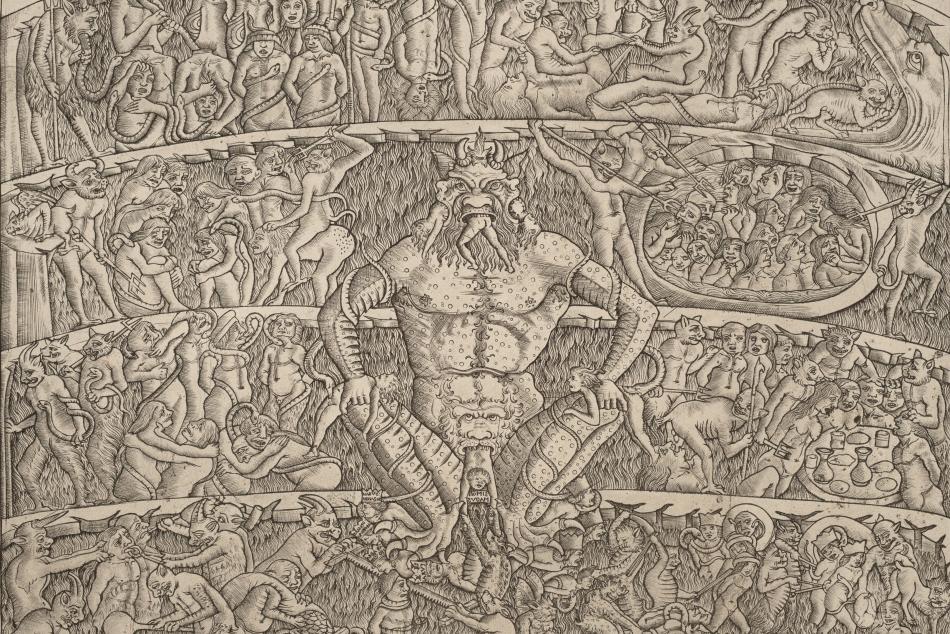

Dante wrote the Divine Comedy in the vernacular, or common language, of his day, which he called Italian. (Most writing at the time was done in Latin, which only the most educated could read.) Part prose and part poetry, the Divine Comedy describes Dante’s journey through Hell (Inferno), Purgatory (Purgatorio), and Paradise (Paradiso), guided first by the ancient Roman poet Virgil and then by his beloved Beatrice.

The National Gallery’s Allegorical Portrait of Dante depicts the poet sitting on a rock, his distinctive profile leaving no doubt as to his identity. He turns to look across the water at small figures walking along the elevated circles of Purgatory, where souls await purification before admission to Paradise. His right hand hovers in a protective or resolute gesture over the bell tower and cathedral (Duomo) of Florence, illuminated from below by flickering flames, perhaps of Hell itself.

In his left hand is a large manuscript copy of his masterpiece opened to the 25th Canto of Paradise. Legible lines focus on Dante’s desperate hope and longing to return to the place of his birth after so many years in exile. A few of the translated lines read:

If it should happen . . . If this sacred poem—

this work so shared by heaven and by earth

that it has made me lean through these long years—

can ever overcome the cruelty

that bars me from the fair fold where I slept,

a lamb opposed to wolves that war on it,

by then with other voice, with other fleece,

I shall return as poet and put on,

at my baptismal font, the laurel crown.

Dante writes of the wolves and the lambs of war, the cruelty of the strong over the weak. Seven hundred years after his death such evocations have relevance again, as they often have had throughout history.

You may also like

Article: Going through Hell? See Dante’s “The Divine Comedy” in Art

Travel with artists through Dante’s Nine Circles of Hell.

Article: How Herb and Dorothy Vogel Built One of the Greatest Modern Art Collections—and Then Gave It All Away

These unassuming art collectors fit more than 4,000 works in their tiny New York City apartment, all while working as a librarian and postal clerk.