Quilts That Embody the Legacy of Black America

About an hour southeast of Selma, on a horseshoe bend of the Alabama River, sits Gee’s Bend, a town of roughly 200 people whose homemade quilts hang in museums and galleries worldwide.

A 14-mile trail of wooden billboards reveals the legacy of the town and its quilting matriarchs. A red-and-black checkerboard inside an orange-and-gold medallion honors Patti Ann Williams. Multicolored strips imitating Arlonzia Pettway’s abstract designs look remarkably like Ghanaian kente cloth. And the minimalist geometric patterns of sky blue, white, and indigo pay tribute to Loretta Pettway Bennett, who can probably be found at the community center just off the main road.

The 61-year-old teaches quilting to anyone who stops by. There are no scheduled hours, but someone will be around to help with hand stitching or laying out fabric. Nearly everyone in Gee’s Bend is cousin and kin to one another. Nearly everyone quilts, men and women. And the quilting is continuous, just like their history.

How Gee’s Bend Got Its Name

Gee’s Bend is named for Joseph Gee, a North Carolina entrepreneur who bought land in Alabama for its fertile plains and built a cotton plantation in 1816. The plantation housed 17 enslaved people who planted cotton seed in the spring and pulled and ginned cotton into the fall and winter. Gee died in 1845, and his nephews, having inherited the plantation, sold the land and slaves to another relative, Mark Pettway. Pettway was a cruel man who made his slaves walk from North Carolina to Alabama. Now Pettway’s property, some of the Gee’s slaves were forced to adopt his last name—a name many Gee’s Bend residents still carry five generations on.

The Black residents of Gee’s Bend stayed on the land throughout the Civil War and after Emancipation in 1863. But when cotton cashed out in the 1920s, white merchants revoked their credit, forcing them into poverty.

The federal government eventually bought the Gee’s plantation, parceling out the land to the formerly enslaved Pettways. Gee’s Bend became an isolated community of Black landowners. But the Depression started the first exodus. “There used to be a lot of people here,” says Mary Margaret Pettway, Loretta’s cousin.

Still, many of the Pettways knew the value of land and held onto it. Mary Margaret says that’s when her Aunt Lucy—Loretta’s mother—and other women in Gee’s Bend began making quilts to financially support their families and farms.

Quilting in Gee’s Bend

Some of the Pettways still talk about the original quilter, Dinah Miller: kidnapped from an unknown land in Africa, sold for a dime, and brought to Alabama in 1859 to work Pettway’s plantation. They say she planted the seeds that made quilting blossom and germinate among the enslaved Pettways. Teaching quilting both increased their value to their owners and kept them warm in their chilly cabins.

Unlike the organized, precise patterns that many white quilters made from Dutch and English designs, African American quilts were often raw and vibrant. They were stitched by hand with imagination and resourcefulness; old cotton dresses, frayed ribbon, and cotton seed bags offered unusual color palettes and textures. Enslaved people weren’t allowed an education, so quilting lessons were passed down from family member to family member.

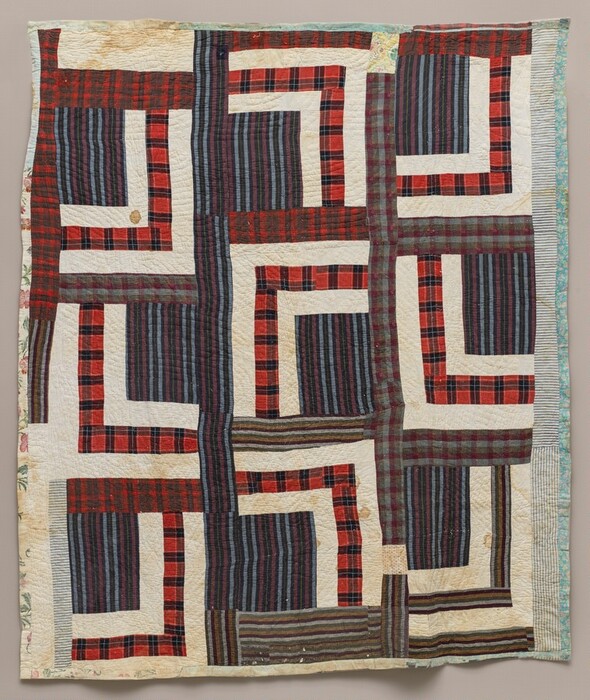

Mary L. Bennett’s “Lazy Gal” Variation (2003) is on the left in this view from the exhibition Called to Create: Black Artists of the American South.

The Quilts Become Popular

Lucy Pettway was one of the second-generation quilters who discovered the gifts that worn scraps and century-old patterns would bring to a decaying town on the river’s horseshoe bend. She and other family members made geometric workwear quilts named “Lazy Gal” or the “Nine Patch.” Made from corduroy, tattered aprons and ripped denim overalls, the quilts reflected the isolated town’s struggle sharecropping cotton and working sweet potato and corn fields with no money, running water, or electricity.

The quilts were a blessing for the town: bold, colorful, and reminiscent of modern art, their distinct styles became popular beyond Gee’s Bend. By 1962, so many people wanted to visit the solitary enclave of Black quilters, a ferry began carrying both white and Black tourists to see the amazing quilts and their multigenerational designers.

Mary Margaret Pettway stitches a quilt. Photo © Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio

Even dignitaries like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. visited Gee’s Bend. In 1965, he told the residents that they were crucial to the fight for civil rights and that their quilts gave him and other activists renewed strength to keep marching.

But Dr. King’s visit provoked racist backlash: the county sheriff grounded the county ferry. “We didn’t close the ferry because they were Black,” he was quoted saying. “We closed it because they forgot they were Black.” (County officials continuously voted down a replacement ferry for the next 40 years.)

But nothing could stop the fascination with the Gee’s Bend quilts. A white Episcopal priest from Mobile got lost near the town and spied some quilts hanging from a clothesline. He believed the quilts could raise money for Southern women in the civil rights movement and arranged to sell them at a New York auction. There, the quilts attracted influential artists like Lee Krasner. Fashion editor Diana Vreeland promoted them in Vogue magazine, and they sold at luxury department stores like Saks Fifth Avenue.

Not only did the quilts make money but they also taught the women of Gee’s Bend the value of their talents. They started the Freedom Quilting Bee in 1966, dedicated to increasing the economic stability of their small community and improving the lives of their children.

Mary Margaret Pettway works on a quilt. Photo © Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio

Mary Margaret Pettway’s Influence

“When we were first learning to quilt, we were rushing to get outside,” laughs Mary Margaret. “My mother said I had to do it.”

Mary Margaret is now a member of the Gee’s Bend Quilting Collective and board chair of Souls Grown Deep Foundation, which works for the preservation and recognition of Black Southern art.

Although Mary Margaret’s mother Quinnie was a well-known quilter, she made simple, traditional patterns. Mary Margaret was heavily influenced by her father’s sisters: Lucy T. Pettway, Revil Mosley, and Ruth Pettway Mosley. The New York Times called their nontraditional quilts “Some of the most miraculous works of modern art America has produced.”

Aunt Lucy taught Mary Margaret the differences between hand sewing and machine stitching, how to frame a quilt, how to create historic patterns, and the freedom of abstract work—all passed down from her grandmother, Mary Ann. Eventually, Mary Margaret says, she could look at a finished quilt and tell whether her mother or one of her aunts had made it. “Not everyone quilts alike,” she insisted. “Some of them do long stitches, or irregular ones. The older people are so precise.”

Learning their skills inspired her own quilt work. Using threads and cloth that mimic nature’s palette or creating the complex spirals of the Dutchman’s Wheel—12-block star patterns bursting with color, like a kaleidoscope—Mary Margaret’s quilts embody the legacy of Black America. They are so important, they were the influence for the dress Michelle Obama wears in the legendary painting artist Amy Sherald made for the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery.

Irene Williams’ Blocks and Strips (c.1980) in the foreground, with Sue Willie Seltzer’s Columns of Block (2003) on the right, in Called to Create.

The Legacy of Quilting—and Gee’s Bend

“[Quilting is] so important to the history of Black people,” says Mary Margaret. “I don’t want it to be a lost art.” Many Gee’s Bend families left to go to school or find work. Now elders are slowing down and unable to quilt. Arthritis grips their hands. Diabetes makes it tough to see those intricate stitches.

Nevertheless, Mary Margaret and Loretta believe the Gee’s Bend quilts hold power—not just with the museum visitors or Oprah viewers, but with a new generation of artists: Bisa Butler’s vibrant quilts reflect Black life, blurring the line between contemporary and folk art. The colorful, defiant quilts of New York artist Jeffrey Gibson tackle multiple questions about his indigenous heritage, queer history, and popular culture.

The more people learn about their family’s history, Mary Margaret and Loretta say, the more they value where they come from. Many of the younger Pettway cousins are starting to make their first quilts.

“They see the legacy of continuing quilt-making,” says Mary Margaret. “I am so proud of that.” Maybe—just maybe—the family tradition will bring more of them home to Gee’s Bend. “I left for a while. But I always came back,” Mary Margaret reflects. “It’s home. It’s this place. It’s family.”

“It’s being close to our ancestral roots,” says Loretta. “I feel so at peace when I come here—a peace I can’t get anywhere else.”

Can anybody quilt? “Anyone can learn, if they have the desire,” Loretta explains.

“I can’t be dippin’ into other people’s business when I’m doing it,” laughs Mary Margaret. “It’s pure peace. Some say it’s therapeutic.”

She pauses for a moment, then adds: “It’s good for the soul.”

Top image: Quilts hanging from a fence during the annual Gee’s Bend Airing of the Quilts Festival. Photo © Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio

You may also like

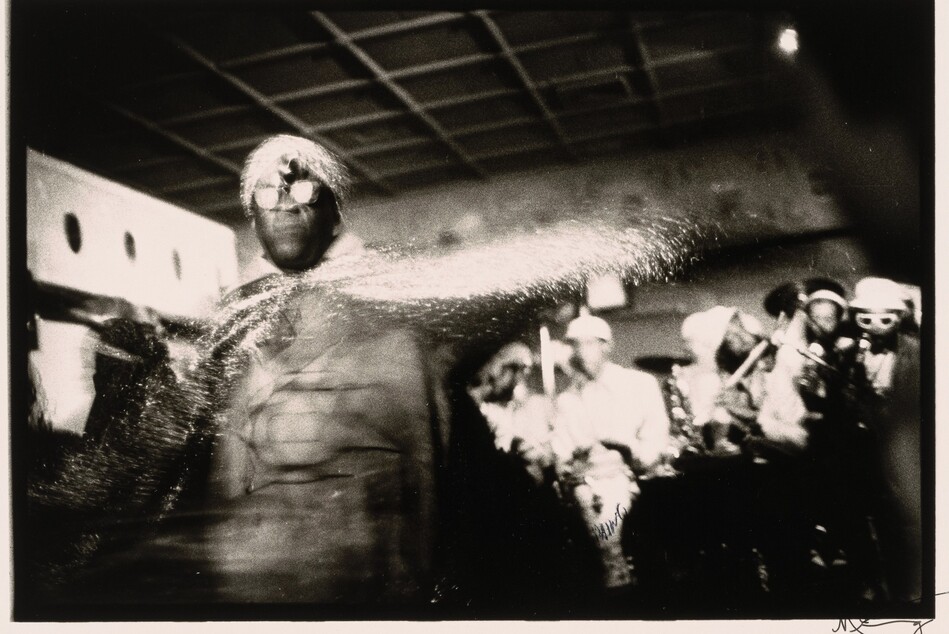

Article: What Is the Black Arts Movement? Seven Things to Know

Learn how the "cultural revolution in art and ideas" celebrated Black history, identity, and beauty.

Article: Who Is Elizabeth Catlett? 12 Things to Know

Meet a groundbreaking artist who made sculptures and prints for her people.