What is German Expressionism? 8 Things to Know

A pandemic, wars, social unrest, political clashes, and economic instability. Sound familiar? Like many of us today, Europeans in the early 1900s felt anxious and uncertain about the world. In Germany and Austria, artists and collectives channeled that energy into a new style. Today, we call them the German expressionists. But did they all see themselves as part of that movement?

Read on to learn about German expressionism: its origins, artists, inspirations, styles, and more. You can explore further in our exhibition The Anxious Eye: German Expressionism and Its Legacy, on view from February 11 through May 27.

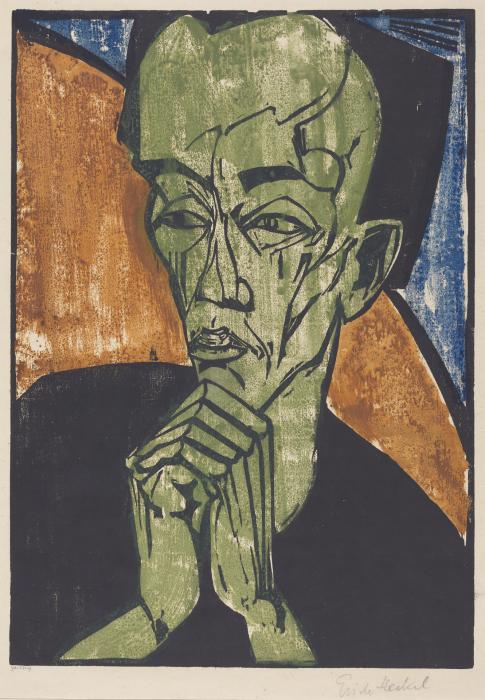

Erich Heckel, Man in Prayer, 1919, hand-colored woodcut, Rosenwald Collection, 1943.3.9081

© 2023 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

1. It originated with two collectives looking for new art styles

A group of aspiring artists in Dresden, Germany, at the beginning of the 20th century found common cause. Erich Heckel, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, and Fritz Bleyl believed that art should reflect and cause emotions and states of mind. Not satisfied with the conventional artistic styles of the day, they began meeting to dream up new ideas. In 1905 they formed a group named Die Brücke (the Bridge), believing that their new approach could link the past and the future. Their manifesto called on artists to join them: “Whoever renders directly and authentically that which impels him to create is one of us.”

Around the same time, a group in Munich was exploring the spirituality of abstract art. In 1911 Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc began organizing exhibitions as Der Blaue Reiter (the Blue Rider). According to Kandinsky, the name combined Marc’s love of horses and Kandinsky’s of riders with their shared favorite color: blue. Der Blaue Reiter also included artists such as Paul Klee, August Macke, Gabriele Münter, and Marianne von Werefkin.

Both groups were short-lived. By the start of World War I in 1914, they had disbanded.

2. It is bold, colorful, and psychological

The dozen or so artists we associate with German expressionism each had their own style. Nevertheless, their art does have some things in common.

In order to both represent and stimulate emotions, German expressionists were bold. Their paintings, prints, and sculptures were direct. They simplified forms, flattened perspective, and got rid of extra details. Rather than precisely representing people or places, their art captured essences or feelings. Their works draw our attention to people’s facial expressions and their relationships.

How they made their art also reflected emotions. Earlier artists had tried to hide any trace of the artist’s hand. But German expressionists used thick strokes and heavy lines that conveyed their effort. Visible brushstrokes or marks heighten the drama of their works.

German expressionists often favored unconventional colors. They used a range of vibrant hues, which often clashed. Der Blaue Reiter artists like Kandinsky believed that colors called up particular emotions. For example, he considered red “assertive” and “forceful.”

Käthe Kollwitz, Self-Portrait (Selbstbildnis von vorn), 1923, woodcut, Rosenwald Collection, 1947.12.67

© 2023 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

3. Early psychology influenced its focus on people

People are at the center of most German expressionist art. At the time, pioneers of the emerging field of psychology Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung were sharing new ideas about human behavior and the subconscious. This influenced artists such as Käthe Kollwitz, who used herself as a model and visualized her feelings. Other artists used friends, families, lovers, and patrons as sitters. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner even used his psychologist, Dr. Ludwig Binswanger.

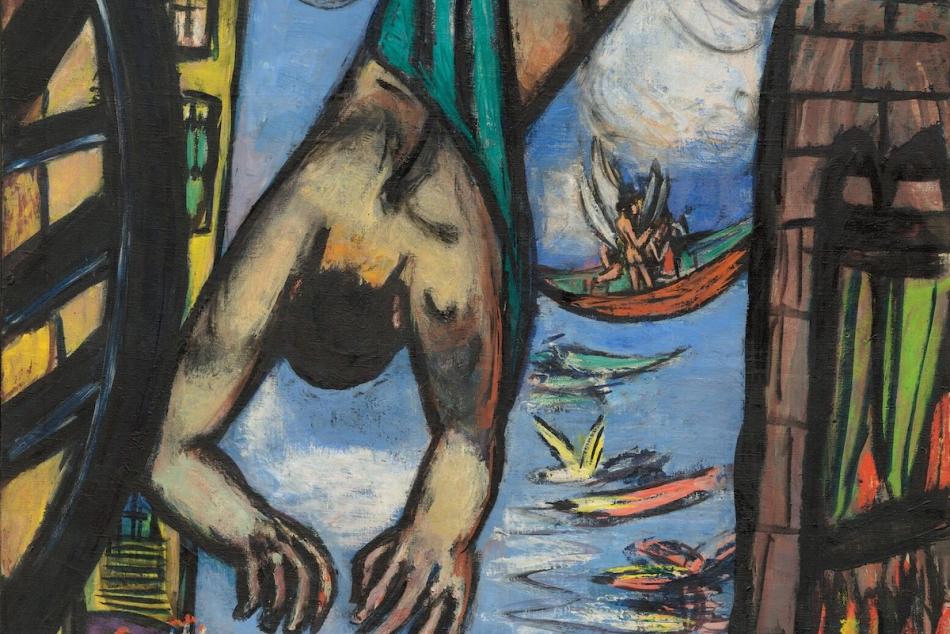

German expressionists were also interested in how our bodies reveal our thoughts. Egon Schiele explored this in his prints. In works like Sorrow, anonymous figures embody a state of mind or an emotion. Many works feature nudes. Bare of clothing and any associations with modern life, the naked human body directly conveys primal feelings.

George Grosz, Attack (Attentat), 1915, lithograph in black on laid paper, Purchased as the gift of Richard A. Simms and Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 2017.100.1

© 2023 Estate of George Grosz / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

4. World War I deeply affected the artists

As World War I unfolded in 1914, many artists were drafted or volunteered to serve in the military. These include Max Beckmann, Erich Heckel, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Max Pechstein, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. Franz Marc and August Macke both died in battle. The war also weighed heavily on those who survived—many suffered physical injuries and psychological trauma. Some, like Kollwitz, lost children or family.

Otto Dix processed his experience as a machine gunner through his prints. His series Der Krieg (The war) show graphic and horrific images based on his memories of the war. Other artists sought comfort in nature. Kirchner, who suffered a nervous breakdown while serving in the war, took solace in the majestic Swiss Alps. Scenes like Two Bathers on the Fehmarn Coast (Zwei Badende am hoher Fehmarnküste) represent regular escapes to nature he and other artists made.

The war’s end in 1918 did not bring peace to Germany. Nearly 2,750,000 German soldiers and civilians had died. Political and social unrest and a regime change followed. This led to a rise in antisemitism, persecution of homosexuality, gender biases, and nationalism which empowered the creation of Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Party. Germany’s economy was in crisis thanks to a significant national debt and war reparations.

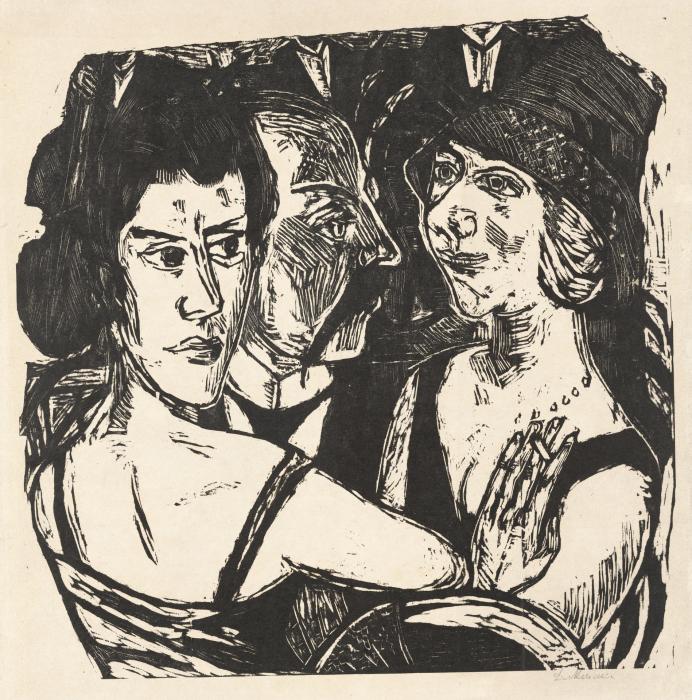

Max Beckmann, Group Portrait, Eden Bar (Gruppenbildnis Edenbar), 1923, woodcut on heavy Japan paper, Rosenwald Collection, 1964.8.319

© 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

5. It now includes artists who didn’t identify as expressionists

Some of the artists we now call German expressionists worked independently from the major collectives. Lovis Corinth, for example, rejected any association with them. But his style and subjects mirror the movement.

While today he is known as a German expressionist, Max Beckmann did not identify with the group. He excluded expressionist artists from exhibitions he organized and publicly criticized their abstract approach. Instead, he was part of a counter group formed in the 1920s: Neue Sachlichkeit or New Objectivity. Led by Beckmann, Otto Dix, and George Grosz, the group challenged the expressionist focus on the abstract or ideal. It called on artists to pay attention to the world around them. Neue Sachlichkeit artists represented modern scenes of Germany’s bustling cities, often showing isolated or detached people in urban settings.

6. It was inspired by postimpressionism and appropriated African and Oceanic art

German expressionists looked abroad for inspiration. Some consider Norwegian painter and printmaker Edvard Munch the father of the movement for his boldly colored, abstracted, the intensely psychological works.

The bright colors and thoughtful portraits of postimpressionist Vincent van Gogh also resonated with German expressionists. Similarly, Paul Gauguin appealed to them because of his vibrant palette and simplified forms. But the expressionists were also interested in the way Gauguin incorporated Oceanic imagery from his time in Polynesia.

German expressionists were exposed to the art and peoples of the African countries and Pacific islands colonized by Germany through ethnographic museums and colonial exhibitions. Colonization led to the unregulated trade and theft of art and cultural artifacts as well as the trafficking of individuals for display in living tableaus.

Expressionists appropriated geometric figures, angular shapes, and patterns. Like Gauguin, they projected biases onto their people and art traditions. Even the few that traveled to the colonized countries, like Emil Nolde (who visited Papua New Guinea) and Max Pechstein (who visited Palau), made works that reinforced stereotypes. They furthered the idea that the peoples there were “primitive.”

7. Even as Nazis called it “degenerate” art, some of the artists supported Nazism

In 1937 Germany’s ruling Nazi regime organized an exhibition of Entartete Kunst, or “degenerate” art. They admired classical and traditional works and considered modern and abstract works degenerate and dangerous. Since Hitler’s appointment as chancellor in 1933, the Nazis had removed more than 20,000 artworks from state-owned museums. Many German expressionist works were confiscated and destroyed.

Labeling artists as enemies of the state limited their creative expression. Some lost teaching positions. Some left Berlin or Germany. Jewish artist Paul Gangolf was murdered by the Nazis in the Esterwegen concentration camp.

But not all German expressionists rejected the Nazis. While his works were included in the degenerate art exhibition, Emil Nolde embraced antisemitism and Nazism.

8. It influenced generations of artists

German expressionism has inspired artists for decades—and continues to inspire them today. The 1970s and ’80s saw the neo-expressionism movement among German and Italian artists including A.R. Penck and Francesco Clemente. In their works, they revived a focus on the emotional impact of the figure.

Today, we find ourselves in a world that echoes the turbulence of the early 20th century. In response, artists like Orit Hofshi turn to the styles and methods of German expressionism. They create works that speak to contemporary issues including displacement, migration, and the ravages of war and climate change on the land.

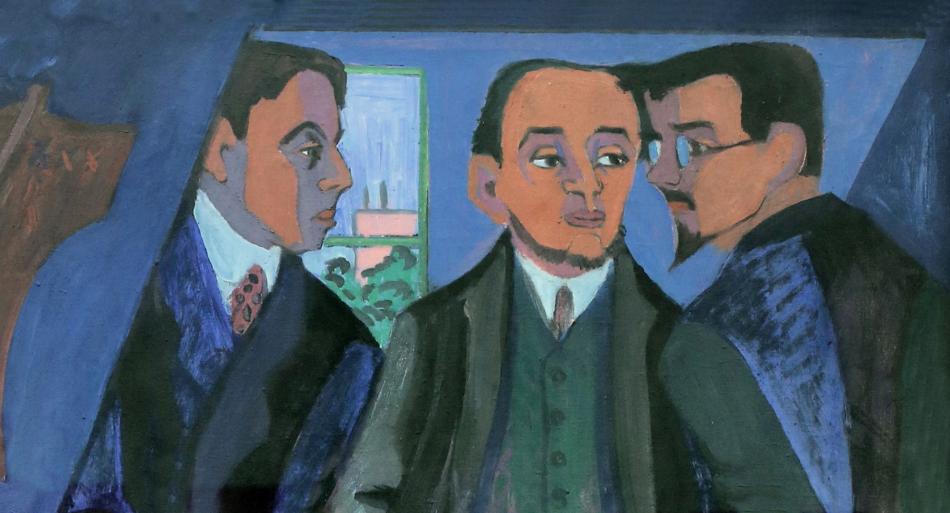

Banner image: A detail of painting of members of Die Brücke (the Bridge). Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Eine Künstlergemeinschaft (Die Maler der Brucke) [An Artists’ Group (The Painters of the Brücke)], 1926/7, oil on canvas, Museum Ludwig, Cologne.

You may also like

Article: What Is Impressionism? 4 Things to Know

Learn the hallmarks of one of the most recognizable art movements in the world.

Article: Poet Naomi Shihab Nye Responds to a Painting by Max Beckmann

The Palestinian-American poet is inspired by "Falling Man" by Max Beckmann, her mother’s teacher.