Who is Anni Albers? 8 Things to Know

Anni Albers was one of the most important textile artists and designers of the 20th century.

Her innovative approach to textiles helped establish the medium as a fine art, not just “craft.” Albers used unusual materials, created daring designs, and considered textiles in relation to contemporary architecture. You can see Albers’s works in our exhibition Woven Histories: Textiles and Modern Abstraction, on view March 17 to July 28.

1. She was born Annelise Elsa Frieda Fleischmann.

Photographer unknown, Lotte and Annelise Fleischmann, ca. 1908. Image courtesy of The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation

Albers was born Annelise Elsa Frieda Fleischmann in Berlin, Germany, in 1899. She was born into privilege. Her father ran a furniture manufacturing business, and her mother came from the family that ran Ullstein Verlag, the largest publisher in Germany.

Anni's family encouraged her artistic interests from a young age. Her mother hired an art tutor when she was around 12. In 1915 her mother brought her to Dresden to meet Austrian expressionist artist Oskar Kokoschka. But Anni's dreams of studying with him were quickly dashed. Kokoschka looked at a portrait she had made of her mother and questioned her motivations for painting.

2. She studied, and taught, at the Bauhaus.

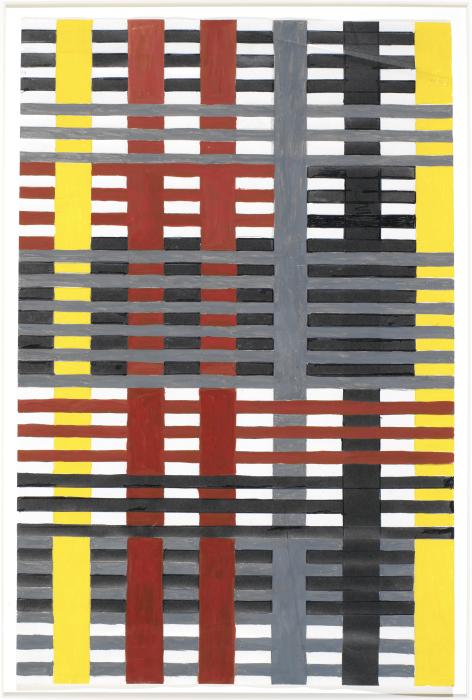

Anni Albers, Design for a 1926 Unexecuted Wall Hanging, not dated, gouache and pencil on reprographic paper, The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation. © 2023 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photocredit: Tim Nighswander/Imaging4Art

Shortly after leaving the school of applied arts, the young artist heard about an innovative new school in Weimar, Germany—the Bauhaus. Founded by architect Walter Gropius in 1919, the Bauhaus brought the fine arts (like painting and sculpture) and applied arts (like metalworking and weaving) together through architecture.

The young Anni applied. After an initial rejection, she succeeded on the second try with help from a student in the Bauhaus glass workshop—Josef Albers. The two would marry three years later in 1925.

After finishing the required introductory course, she entered the weaving workshop. This hadn’t been her first choice. Though Gropius claimed that the Bauhaus would allow women to enter any workshop, in reality they were discouraged from pursuing any field beyond weaving. “I wasn’t a bit interested,” Albers would later explain. “But the only way of staying at that place was to join that workshop.”

But Albers quickly became entranced with weaving. She learned to work on different types of looms. She wove wall hangings and designed industrially fabricated cloth for furniture and interiors. Her work was published in German journals and included in exhibitions. Albers thrived in the weaving workshop under her mentor Gunta Stölzl.

3. She moved to the US because of a chance meeting with architect Philip Johnson.

Anni Albers later designed the curtains for Philip Johnson’s Rockefeller Guest House at 242 East 52 Street, NYC, 1950. Photo: Robert Demora, © Estate of the Artist

In 1933, the Bauhaus closed its doors. Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich had issued an ultimatum to the school—it could only remain open if it agreed to abandon what the Nazis considered “degenerate” art and adopt the retrograde style the regime favored.

Anni and Josef Albers were left without jobs. And because Anni was Jewish, the couple feared for her safety in Germany. Luckily, Anni ran into American architect Philip Johnson. The two had initially met when Johnson visited the Bauhaus. Anni invited Johnson to her apartment for tea.

Upon returning to the United States, Johnson telegrammed the couple with job offers at Black Mountain College in North Carolina. They arrived in New York in November 1933.

4. She inspired a generation of students to pursue textile arts at Black Mountain College.

Helen M. Post, Anni Albers in her weaving studio at Black Mountain College, 1937, courtesy of the Western Regional Archives, State Archives of North Carolina

Like the Bauhaus, Black Mountain College took a progressive approach to education. Based on the theories of its founder John Rice, the school’s philosophy held that the arts were just as fundamental as subjects like math and science.

Josef became the college’s first art teacher and played an important role in developing the curriculum. Anni started a weaving studio. She focused her students on materials. As she later said, “You learn what the material tells you and what the technique tells you.” She developed a course of material studies. Students explored the form, texture, dimensions, and other qualities of everyday objects such as paper, grass, corn kernels, and metal shavings.

Albers would later teach weaving using the ancient technique of a backstrap loom as well as larger, more complex looms. While traditional teaching methods required students to copy historical designs, Albers encouraged her students to let material and technique drive design. She inspired a generation of students to become leading textile and visual artists.

5. She was the first textile artist with a MoMA exhibition.

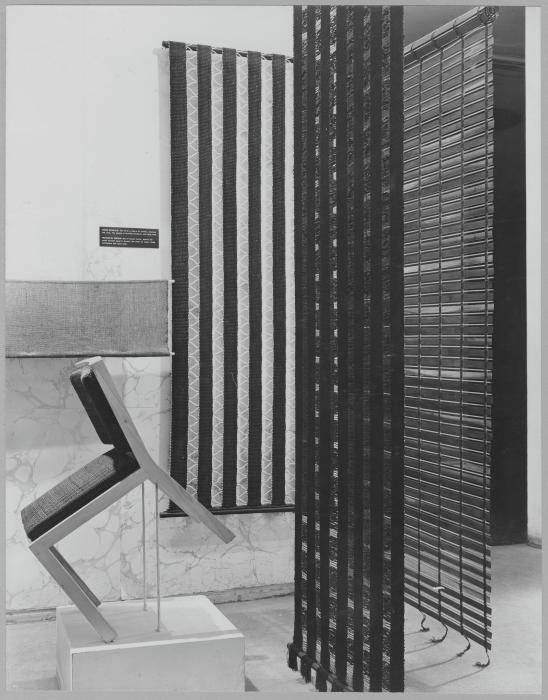

Installation view of the exhibition Anni Albers Textiles (September 14, 1949 through November 6, 1949) at The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Photo by Soichi Sunami from The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

Albers was at the forefront of modern textile design. By the time two of her creations were included in a 1945 Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) exhibition on textile design, the press release listed her as “well known.”

In 1949 Albers became the first textile artist to have a solo exhibition at MoMA. It emphasized her experimental approach to weaving and innovative use of synthetic and natural fibers. The dynamic display featured free hanging “room dividers,” woven partitions suspended from the ceiling. Albers considered these architectural elements. There was also fabric by the yard, industrially created for interior furnishings. And the exhibition featured what Albers called her “pictorial weavings.”

These were all significant steps in establishing textiles as independent artworks that could stand alongside paintings. Albers recognized the struggle to affirm textiles as fine art in the popular imagination. “I find this great problem that people are so inclined to think of textiles always in this useful sense. They want to sit on it; they want to wear it. And they don’t like to think of it as something that might hang on the wall and have the qualities that a painting or a sculpture has,” she said.

6. She shifted her focus to printmaking—but wove in design elements from textiles.

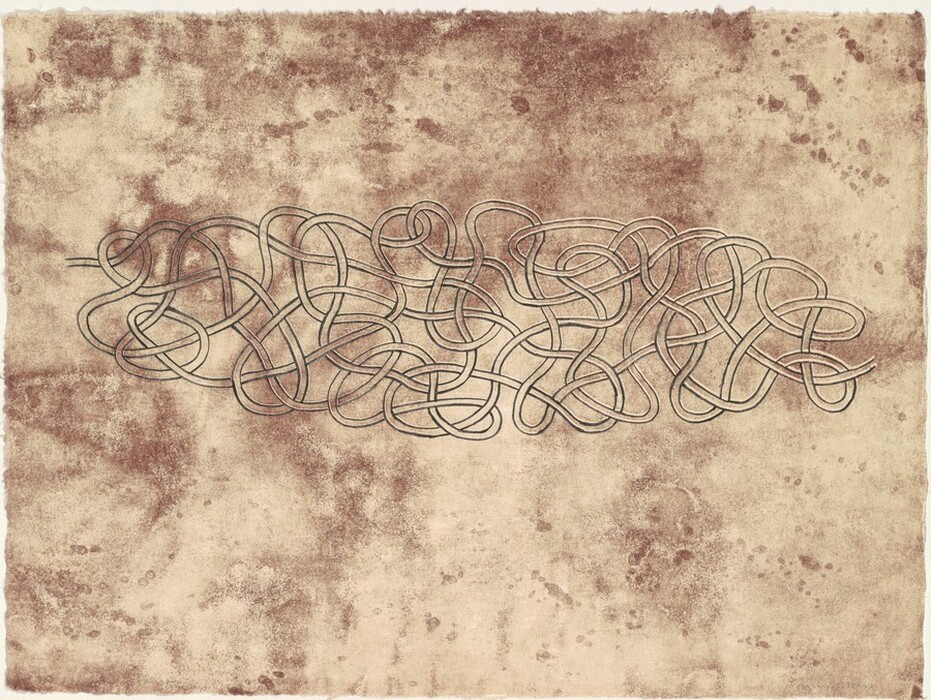

In 1963 Josef Albers had a fellowship at the Tamarind Lithography Workshop in Los Angeles. Anni tagged along with him there, and the workshop’s director June Wayne invited her to experiment with printmaking. That invitation sparked a long-lasting fascination with the medium.

The couple returned to Tamarind in 1964—this time both were fellows. During her fellowship, Albers created a portfolio of lithographs called Line Involvements. These were images of interlacing, threadlike elements. Albers brought everything she had learned from textiles into the new medium. She would focus on printmaking for much of the rest of her life.

Albers made her last weaving in 1968. While she refocused her energy on prints, this didn’t stop her from making textiles. She continued creating designs for industrially woven fabrics in collaboration with furniture design company Knoll.

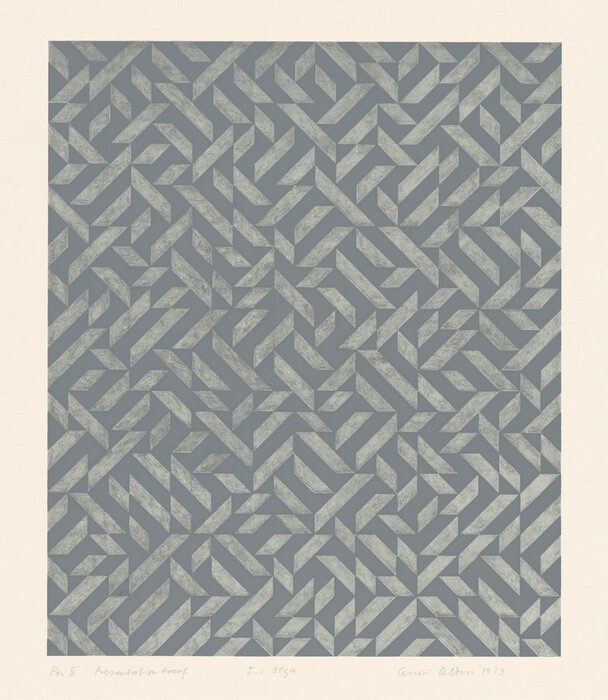

7. She designed one of the best-known modern patterns.

Albers’s best-known pattern is Éclat. She designed it to be woven, but when that proved technically too difficult, it was printed. Éclat is still made today, in a range of different colors. And new technologies have allowed the design to be woven as Albers originally intended.

Named for the French word for sparkle or a shard, the pattern appears random but has an organizing principle that is only revealed after close looking. Albers believed that patterns shouldn’t be immediately obvious to viewers. Their order should be puzzling so that we will “return again and again.”

8. She changed the way we think about textiles.

In 1957, Albers wrote The Pliable Plane. In the essay she argued that textiles are a vital component of the built environment, public and private. Albers felt weavings should be considered part of architectural design. Rather than an “after-thought,” she wrote that weavers and architects could collaborate to create new uses and forms of textiles.

Albers’s impact on textiles stretches beyond her teaching and works. Her writings like The Pliable Plane influenced her contemporaries and continue to inspire artists today.

You may also like

Article: Who Is Dorothea Lange? 6 Things to Know

Learn how the documentary photographer got her start and why she dedicated her life to the medium.

Article: Who Is Marisol? 7 Things to Know

The Venezuelan American artist was wildly famous in the 1960s and ’70s for sculptures that have many sources, but defy categories.