HARRY COOPER:

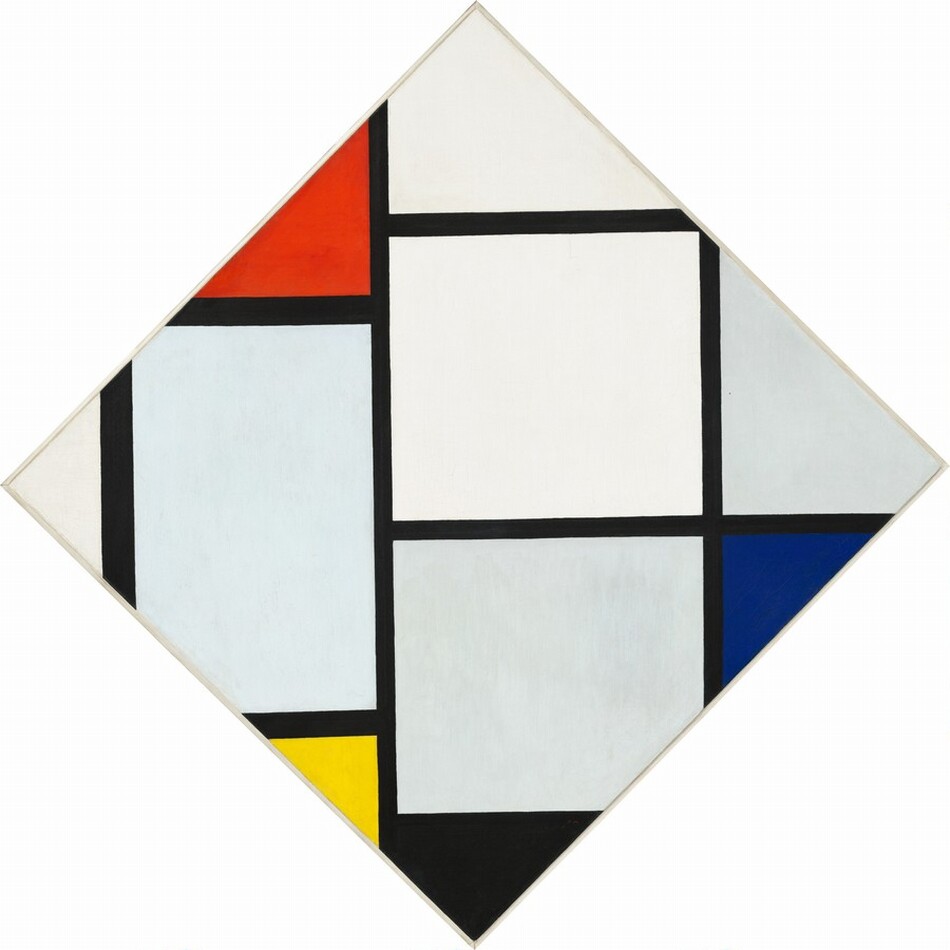

This is a Mondrian. And [laughs] we say “A Mondrian” because he was one of these artists that developed a style. He was part of the movement called “The Style,” or “De Stijl,” in Dutch, which had some very particular rules about how to make abstract art.

NARRATOR:

The rules? Only horizontals and verticals. No symmetry. Primary colors, and white, black, and gray.

Harry Cooper, curator and head of modern art.

HARRY COOPER:

The colors typically are kept at the edges apart from one another, almost as if he doesn’t want us to feel those color interactions. To keep them pure. Purity is certainly a big part of this aesthetic. I think the simplest, maybe most important thing to say about Mondrian is he wanted each element of painting to have its own life, and its autonomy, its own viability.

NARRATOR:

Here he rotated the canvas 45 degrees, but maintained strict horizontal and vertical architecture, which he deemed the essential structure in nature.

HARRY COOPER:

What you get is a real challenge, because almost everything is going to be cut by the edge sooner or later; probably sooner rather than later. So his structure that was so stable and comfortable for him really gets threatened by these edges. Mondrian liked to talk about dynamic equilibrium. I think we start to feel a great deal of dynamism.

It looks simple, but the structure, the complexity is more than we think. I would challenge anybody to look at this for maybe ten minutes, and then turn away and draw it. Draw the basic structure. Not easy to do.