16 Black Artists to Know

Looking to deepen your knowledge of Black artists? Explore the connections between eight pairs of artists in our collection. Some share a similar approach to artmaking, others a specific subject. A few even knew each other personally—two were roommates and two are closely related.

Alma Thomas and Sylvia Snowden

While they were born 50 years apart, Alma Thomas and Sylvia Snowden were both drawn to abstraction. The parallels don’t end there. Decades apart, they both moved to the nation’s capital as children and later studied art at Howard University.

Washington, DC, inspired both Thomas and Snowden. Thomas took inspiration from the flowers in the backyard of her Logan Circle home and throughout the city for her geometric abstractions. Snowden made portraits of people she encountered in her Shaw neighborhood. She used an expressionist technique; thickly applied paint; and, like Thomas, a radiant color palette.

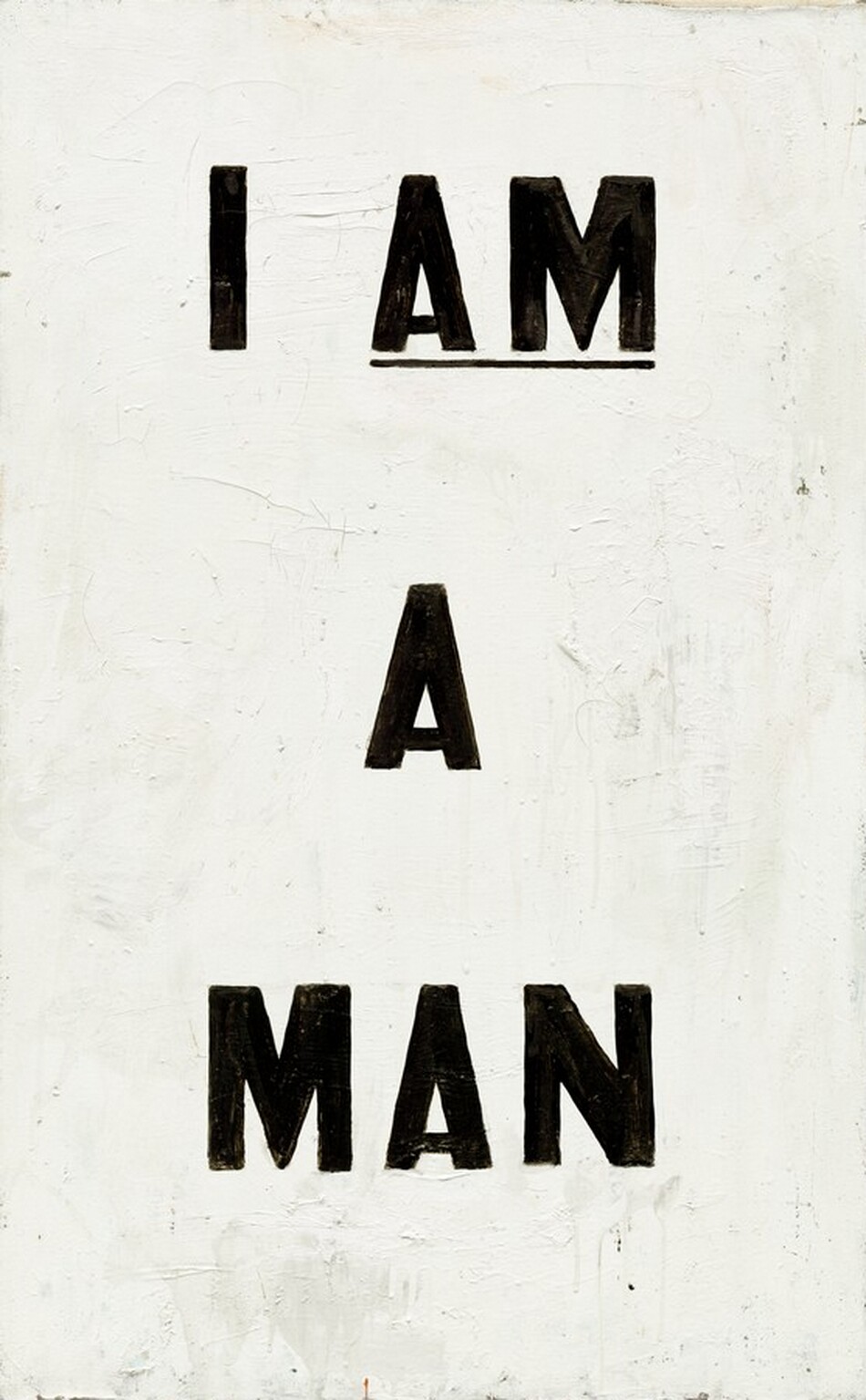

Glenn Ligon and Dread Scott

The works of American artists Glenn Ligon and Dread Scott reference signs that Black sanitation workers in Memphis carried while on strike in 1968. Ligon’s 1988 painting harnesses the power of the text from those signs: "I AM A MAN.” (The words are a variant of “I am an invisible man,” the first line of prologue in Ralph Ellison’s book Invisible Man.) Ligon changed the structure, size, and spacing of the text. He rendered the text in black enamel and made the space around it white using oil paint. That paint has cracked over time, echoing the struggles of its subject.

Another two decades later, Scott wore a sign that read “I AM NOT A MAN” while walking around Harlem dressed in an outfit from the Civil Rights era. Bringing the memory of the 1968 protest to 2008, Scott inserted the word “not,” questioning whether a Black man’s status in society had changed in 40 years. During the hour-long performance, Scott met curious and confused pedestrians and police, as we see in this photograph.

James Van Der Zee and Glenalvin Goodridge

James Van Der Zee was the photographer of choice for New York City’s Harlem neighborhood in the 1920s and ’30s. The area’s majority-Black community visited his studio to sit for portraits, often to commemorate special occasions, and he took particular care in composing those photographs. Van Der Zee offered clients the choice of elaborate painted backdrops, polished clothing options, and an extensive collection of props—like the miniature bulldog in this hand-colored portrait of an adorable little girl.

Seventy years earlier, Glenalvin Goodridge had been one of the first Black photographers in the United States. The Pennsylvania-based entrepreneur opened a studio in York in 1847, within a decade of the introduction to America of the daguerreotype, an early form of photography. Goodridge’s clients visited his studio for a picture of themselves that would “last for ages unchanged,” as he noted in his advertisements.

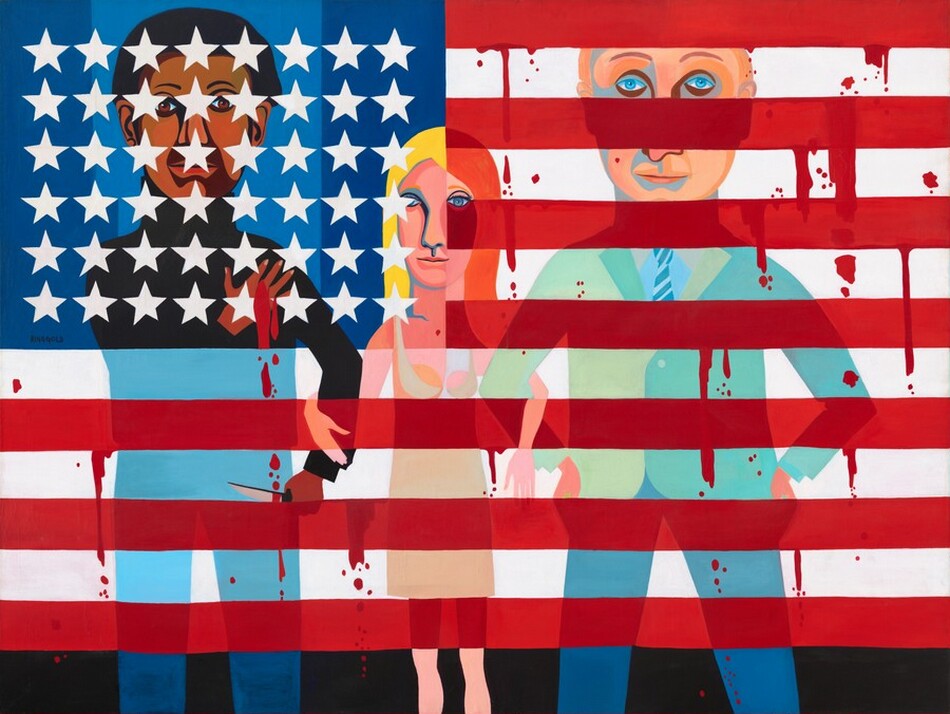

Faith Ringgold and Dindga McCannon

In 1971 Faith Ringgold, Dindga McCannon, and Kay Brown banded together to form Where We At, a collective for Black women artists. The trio was frustrated by their exclusion from the white-dominated art world and male-dominated Black arts movements. They found common ground in their struggles to balance creative pursuits with the responsibilities of motherhood.

Their paintings also reflected their commitment to racial and gender equality. The American People Series #18: The Flag is Bleeding comes from a series of Ringgold’s paintings that represent the racial tensions and political divisions of the 1960s. McCannon’s semiabstract painting Woman #1 is an example of what she calls “imaginative portraiture.” McCannon boldly centered the painting around a pregnant woman at a time when themes of motherhood were typically avoided or shunned by artists.

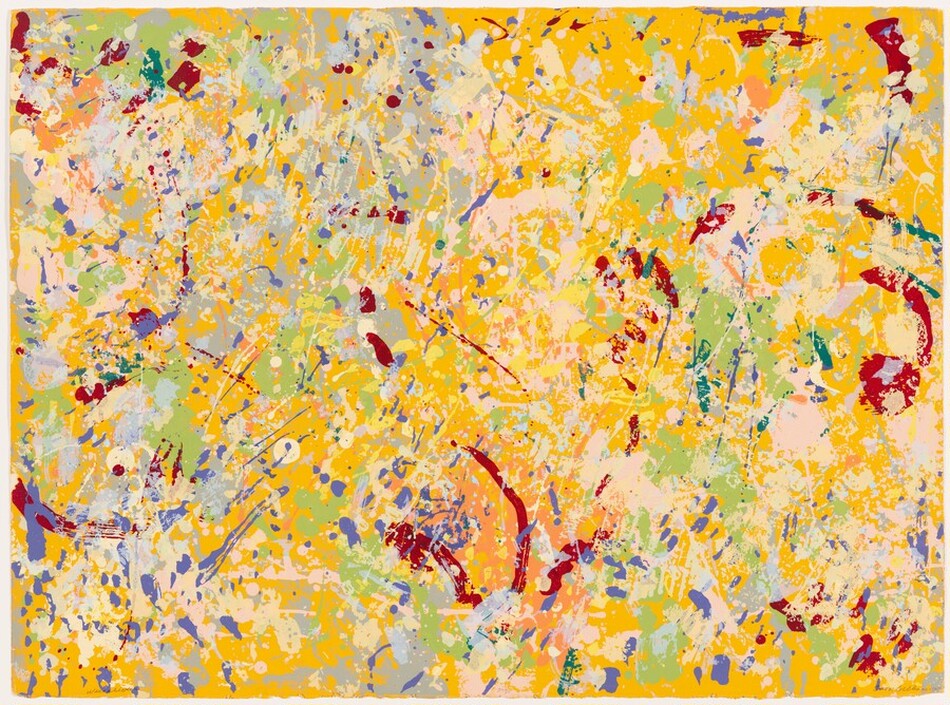

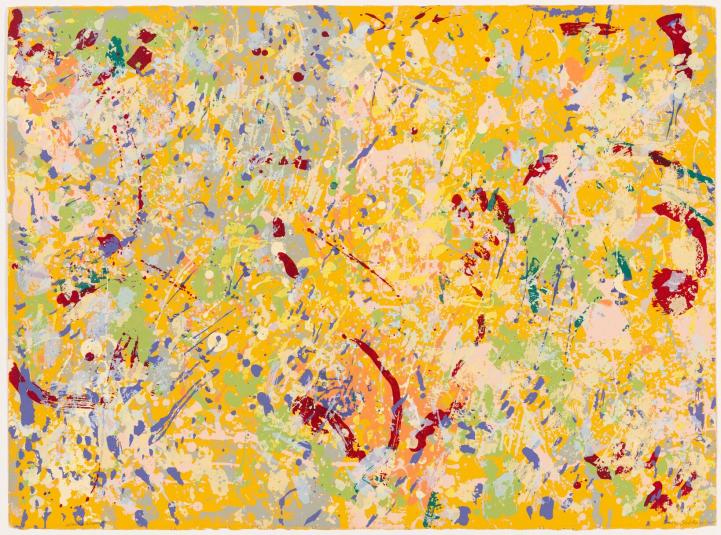

Sam Gilliam and Stanely Whitney

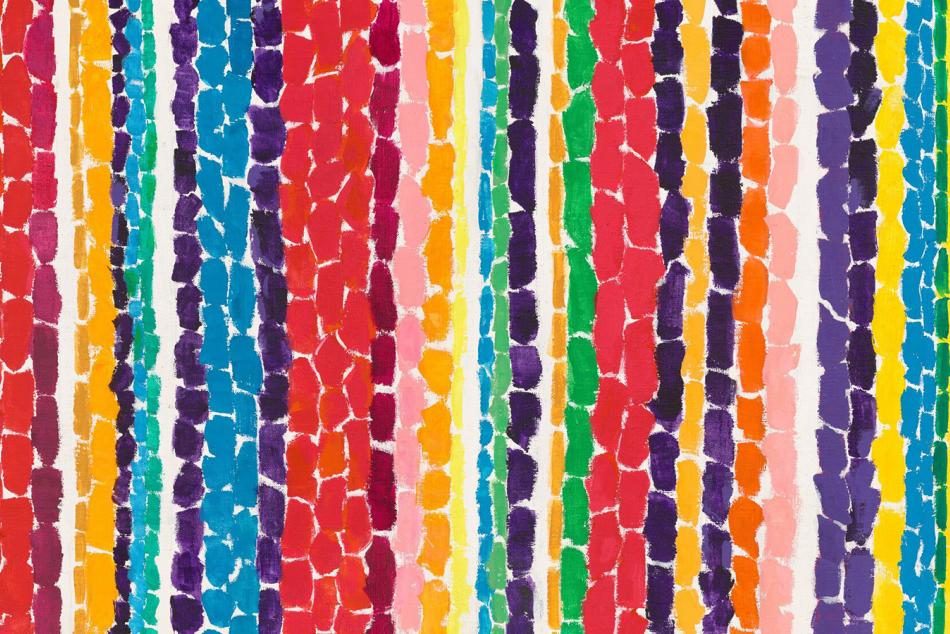

Color is the driving force behind the abstract art of both Sam Gilliam and Stanley Whitney.

Gilliam made a name for himself in the 1960s with innovative paintings that he draped directly from walls. In 1975 he became the first artist in residence at Philadelphia’s Brandywine Workshop. While he was there experimenting with printmaking, Gilliam created this screenprint named for the brook in one of the city’s historic parks, Wissahickon.

Just four years later, Whitney made this untitled screenprint also during a Brandywine residency. While both prints share a vibrant palette, they show how differently the two artists approached abstraction. Gilliam’s strokes of colors are fluid and free formed. Whitney, on the other hand, hints at a grid-like structure in his repeated horizontal and vertical marks. Whitney’s experiments at Brandywine were fundamental to the evolution of his now-signature style of color-blocked paintings.

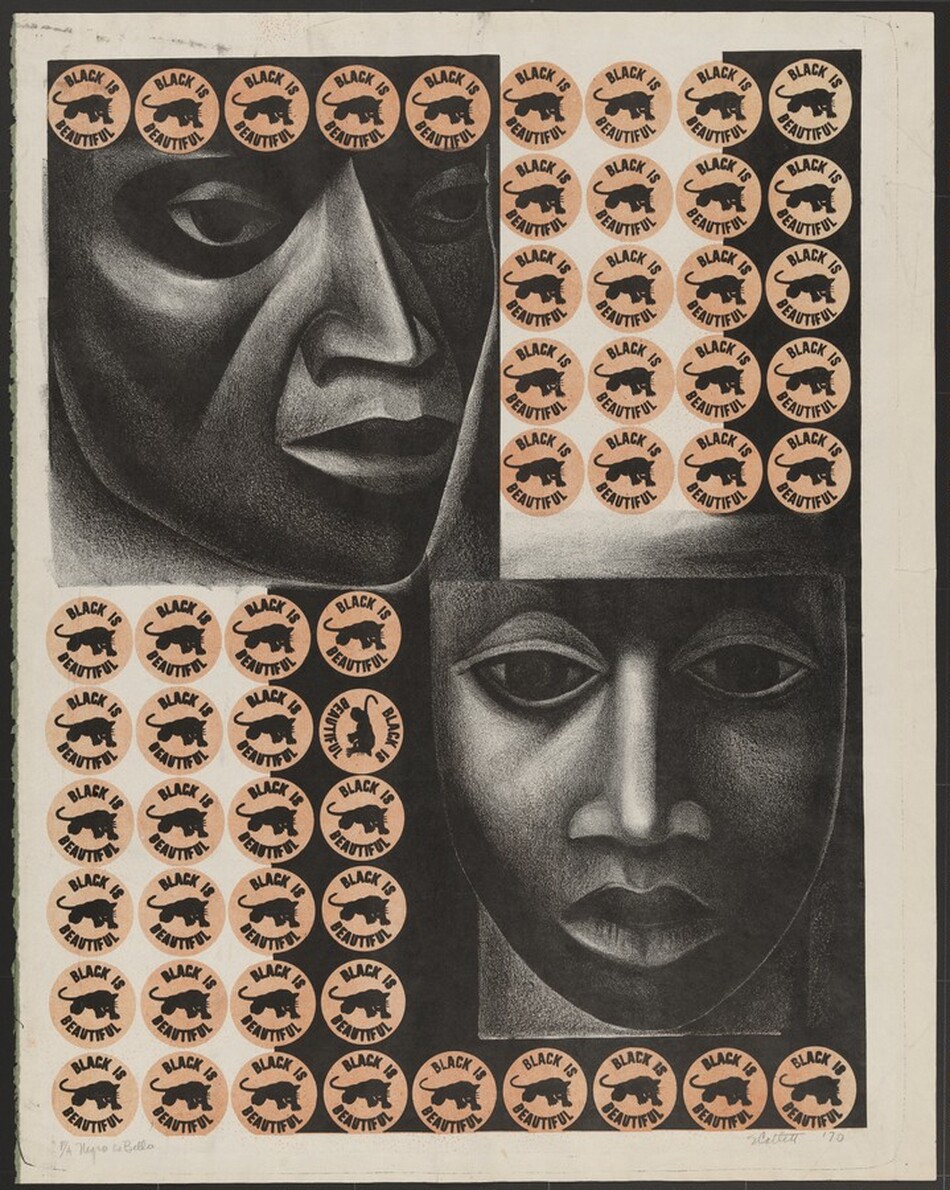

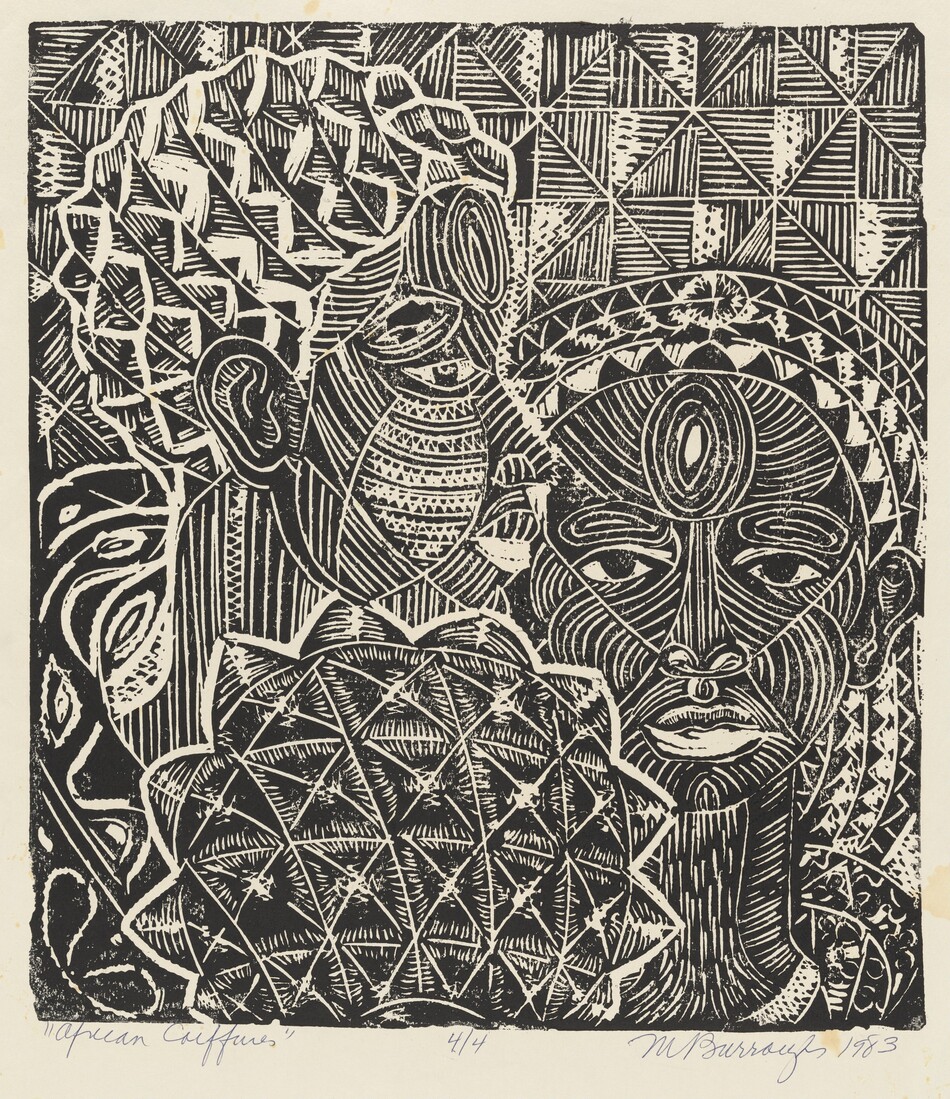

Elizabeth Catlett and Margaret Burroughs

The 1930s and ’40s saw the rise of the Chicago Black Renaissance. Established in 1940 in the city’s Bronzeville neighborhood, the South Side Community Arts Center become a key meeting point for this art and culture movement. Created by a group of artists, the center offered studio, performance, and exhibition space as well as community art classes. Margaret Burroughs was one of the center’s cofounders. The talented artist and educator made paintings, sculptures, and prints; wrote poems and children’s books; and founded the Dusable Museum of African American History in Hyde Park.

In summer 1941 Burroughs shared an apartment with none other than Elizabeth Catlett. Catlett was at the center learning lithography, a printing process she would return to throughout her career. While Catlett wouldn’t stay long in Chicago, she and Burroughs would cross paths again. The two worked together at the Taller de Gráfica Popular (People’s Graphic Workshop) in Mexico City in the 1950s.

Both artists were deeply committed to advancing the rights and stature of African Americans. Both of these prints connect to the refrain "Black is beautiful,” developed during the 1960s Civil Rights movement. The message appears in Catlett’s repeated circles, which also contain the Black Panther symbol. They surround striking images of a Black man and woman. Burroughs’s print focuses on the hairstyles of three different Black women.

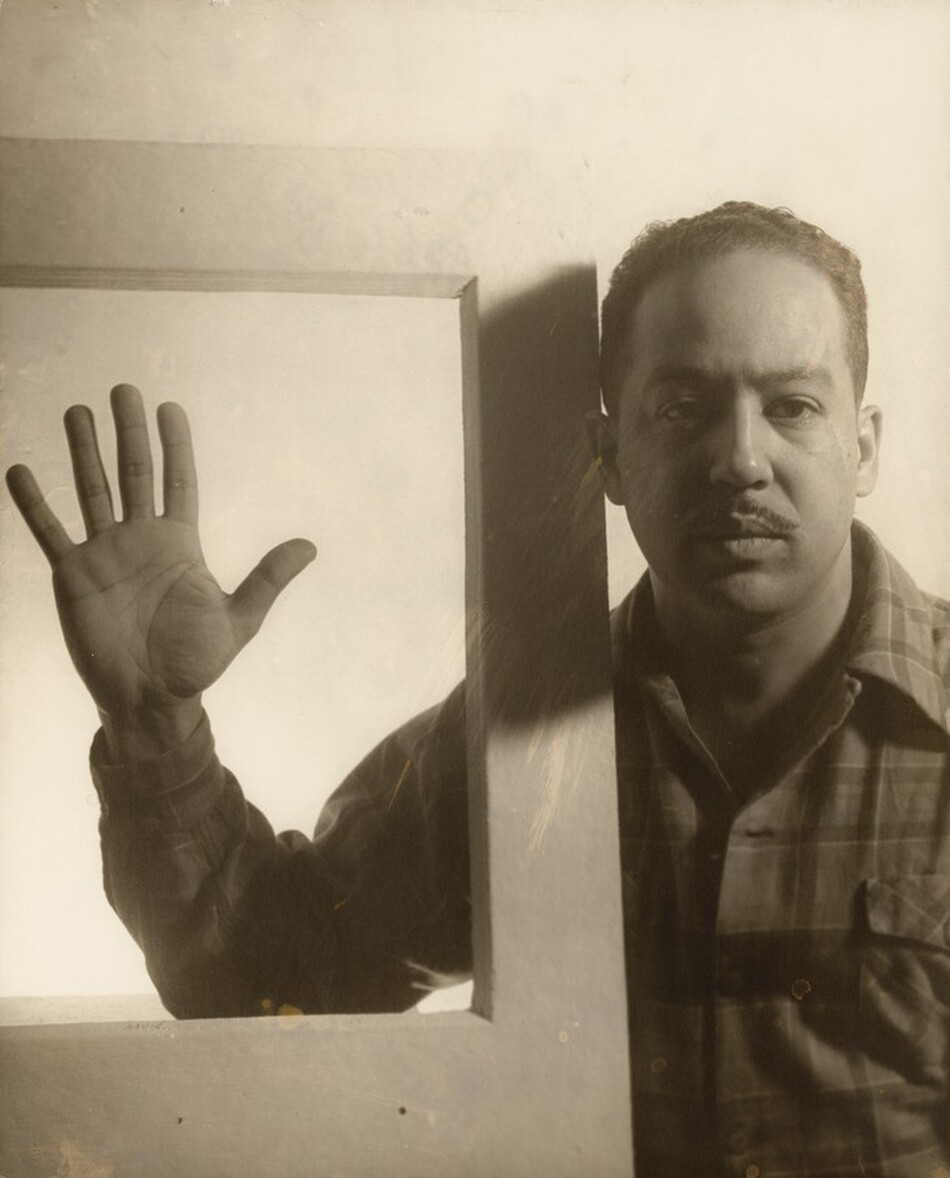

Gordon Parks and Marion Perkins

Early in his career as a photographer, Gordon Parks made some of his earliest prints in a darkroom in the basement of the South Side Community Arts Center. While teaching and working there, Parks crossed paths with some of the most important artists, writers, and scholars of the era, including Catlett, Burroughs, Eldzier Cortor, Charles White, Archibald John Motley Jr., and Alain Locke.

Parks also met writer, poet, and playwright Langston Hughes at the center. This portrait is one of several that Parks took of Hughes. In another, Hughes wraps his arm around a sculpture by Marion Perkins. Perkins carved human figures from stone, often pieces that he had salvaged from buildings. Like Parks, Perkins taught and exhibited his work at the center.

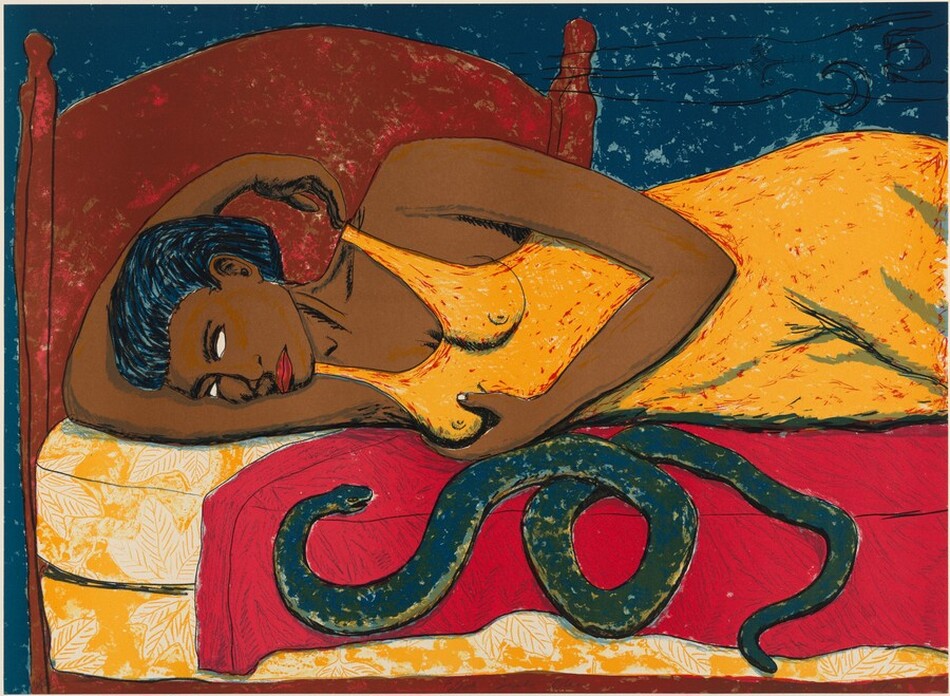

Betye Saar and Alison Saar

Of all the artists listed, these two have the closest connection—they are a mother and daughter. Since 1969, Betye Saar has made assemblage sculptures that explore race, gender, ancestry, and spirituality. The Trickster is a seven-foot-tall antique heater adorned with a necklace of bells, chains, and vintage keys. The sculpture represents Eshu, the Yoruba trickster god who protects devotees while engaging in mischief.

Like her mother, Alison Saar works in a variety of mediums, exploring similar themes. Figures of women are often at the center of her work. The title of Alison Saar’s offset lithograph Black Snake Blues comes from a 1927 song by Victoria Spivey. In the lyrics, Spivey describes a snake that has led her astray. The song and print may reference the biblical story of the snake tempting Eve in the Garden of Eden.

You may also like

Article: Alma Thomas’s Tiptoe Through the Tulips in Living Color

Author and art historian Katy Hessel on the abstract artist's love for flowers.

Article: Your Tour of Black Artists at the National Gallery

These 10 works by Black artists are on view in our galleries, so you can see them during your next visit.