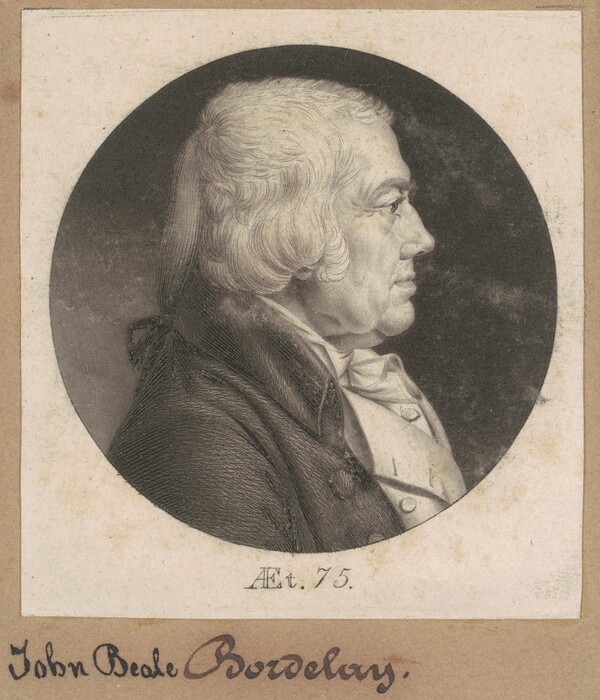

Art up Close: John Beale Bordley’s Revolutionary Portrait

The origins of the Revolutionary War can be found in the details of Charles Willson Peale’s early American portrait.

Revolutionary War paintings are usually dramatic—think Washington Crossing the Delaware by Emanuel Leutze or The Death of General Wolfe by Benjamin West. You might not guess that a quiet portrait sets the stage for battles to come.

Emanuel Leutze, Washington Crossing the Delaware, 1851. Oil on canvas, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of John Stewart Kennedy (1897) 97.34.

Emanuel Leutze, Washington Crossing the Delaware, 1851. Oil on canvas, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of John Stewart Kennedy (1897) 97.34.

In 1770 Charles Willson Peale painted Maryland attorney and farmer (and his close childhood friend) John Beale Bordley. The portrait argued Bordley’s case for why the American colonists deserved freedom from British rule.

A Farmer who Sought Freedom

Bordley was a farmer who believed in American economic self-sufficiency. He brewed his own beer instead of drinking London ale. He grew wheat, a food staple, instead of tobacco, the cash crop that fueled Anglo-American trade. In his portrait, Peale includes other markers of Bordley's financial independence.

The Letter of the Law

Why is Bordley so staunch in his opposition to British rule? Peale lays clues throughout the painting.

Viewers of the time would have recognized this as the answer King Charles I of England gave to the Nineteen Propositions. Passed by the English parliament in 1642, the propositions asked that the monarch share more power with the two parliamentary houses. King Charles I rejecting these demands plunged the country into the English Civil War. The phrase came to refer to the dangers of changing the English constitution.

In Peale’s portrait, Bordley builds his case like a lawyer. The inscriptions weave together a network of meaning, underlining the hypocrisy of British governors levying new taxes on American colonists. These taxes contradicted the spirit of Lex Angli—the English constitution, which stood for justice and liberty. True British citizens would never endure such tyranny from their rulers.

More Symbols of Injustice

Peale painted more scenes and symbols of indignities suffered at the hands of the British at the edges of the painting.

How did these two men know each other?

Behind the revolutionary meanings of this portrait also lies a story of friendship. Peale’s father had served as Bordley’s tutor, and Peale was his close childhood friend. As an adult, Bordley raised funds to send Peale to London to study with acclaimed painter Benjamin West. When Peale returned, Bordley helped him get his first major commission in the American colonies—two life-size portraits, including this painting.

Peale shared Bordley’s strong belief in colonial independence. During the Revolutionary War, Peale served with the Pennsylvania militia against the British. He carried his miniature case to paint portraits of fellow officers.

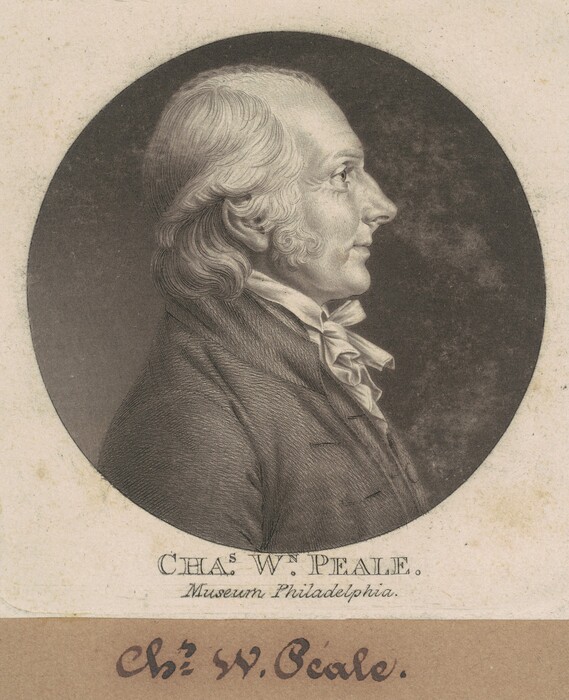

Together, Peale and Bordley supported each other's careers and fought for American independence. They are immortalized in Charles B. J. Févret de Saint-Mémin’s engraved portraits.

You may also like

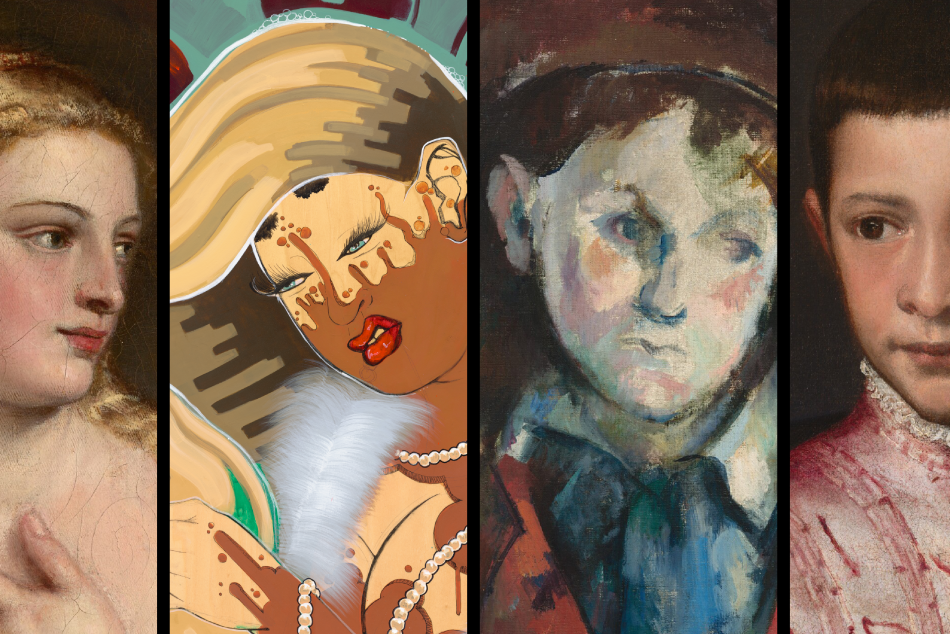

Interactive Article: Four Paintings Speak to Each Other Across Space and Time

See how Titian, Cezanne, and Rozeal. remix and reinterpret conventions for painting people.

Interactive Article: Layers of Power in "The Feast of the Gods"

At first glance, this painting looks like a great party. But it’s more complicated than that.