Language

On this Page:

Overview

What is a portrait? What truths and questions does a portrait communicate?

What might a portrait express about the person portrayed? How does it reflect the sitter’s community, setting, family, or friends? What does the portrait reveal about the artist?

The basic fascination with capturing and studying images of ourselves and of others—for what they say about us, as individuals and as a people—is what makes portraiture so compelling.

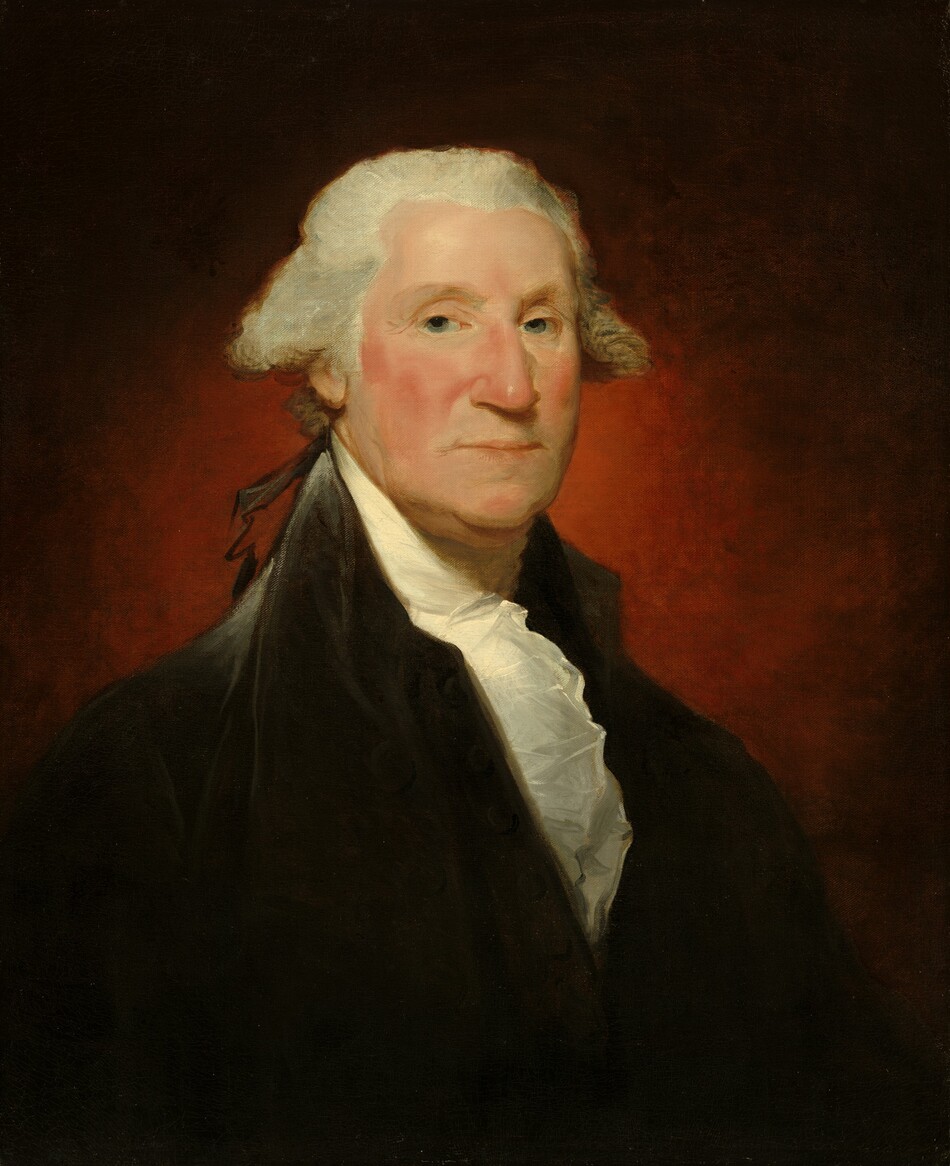

For centuries, portraits have formed an important record of America’s people. When you think of the nation’s first president, the image that comes to mind is likely one created by portraitist Gilbert Stuart, George Washington (Vaughan portrait), 1795. Gilbert captures a broad-shouldered, ruddy-faced, and serious president who eyes us directly, full of character and probity. We know America’s early colonists, leaders, politicians, merchants, and philosophers through their portraits. Very consciously, these individuals constructed, with artists, public memorials of how they wished to be remembered by future generations. They projected their personal qualities, such as prudence, leadership, and strength; their accomplishments, whether military, professional, or intellectual; and their social role or position, such as matriarch, landowner, or politician.

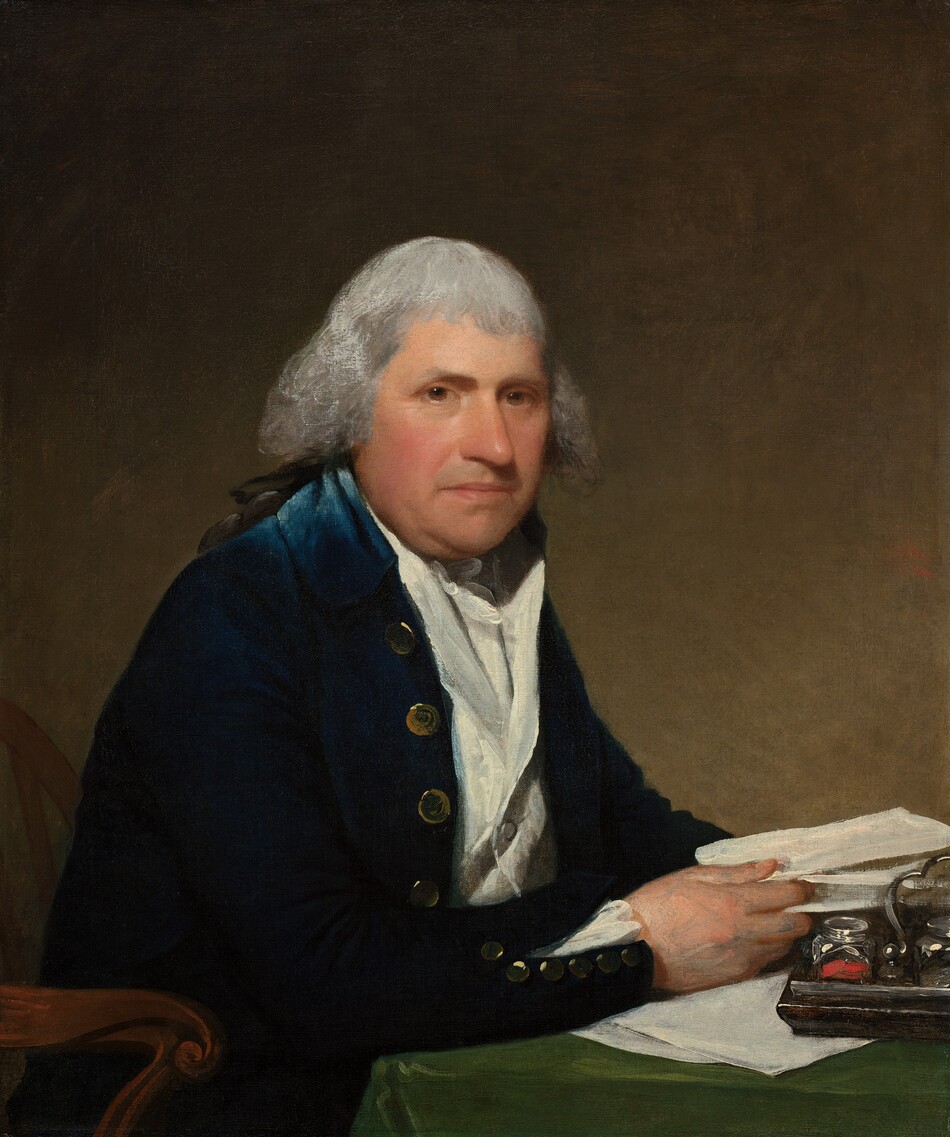

Access to portraits in colonial America and during the republic’s early years was limited. Portraits were available to very few, largely European colonists or immigrant Americans—those who could afford this costly luxury (and a home to place it in). Gradually, as the economy grew, an entrepreneurial class of often self-trained portraitists began to serve a growing middle class who wished to preserve their likenesses for personal, rather than public, reasons, such as to record their family lineage for posterity. Joshua Johnson, among the few African American artists practicing in the area of portraiture during the early 19th century, painted many such family documents, including Grace Allison McCurdy (Mrs. Hugh McCurdy) and Her Daughters, Mary Jane and Letitia Grace, circa 1806. Its domestic setting (the subjects sit on a high-back sofa) and the intimacy and tenderness conveyed by mother and daughters distinguish it from Gilbert Stuart’s public portraiture.

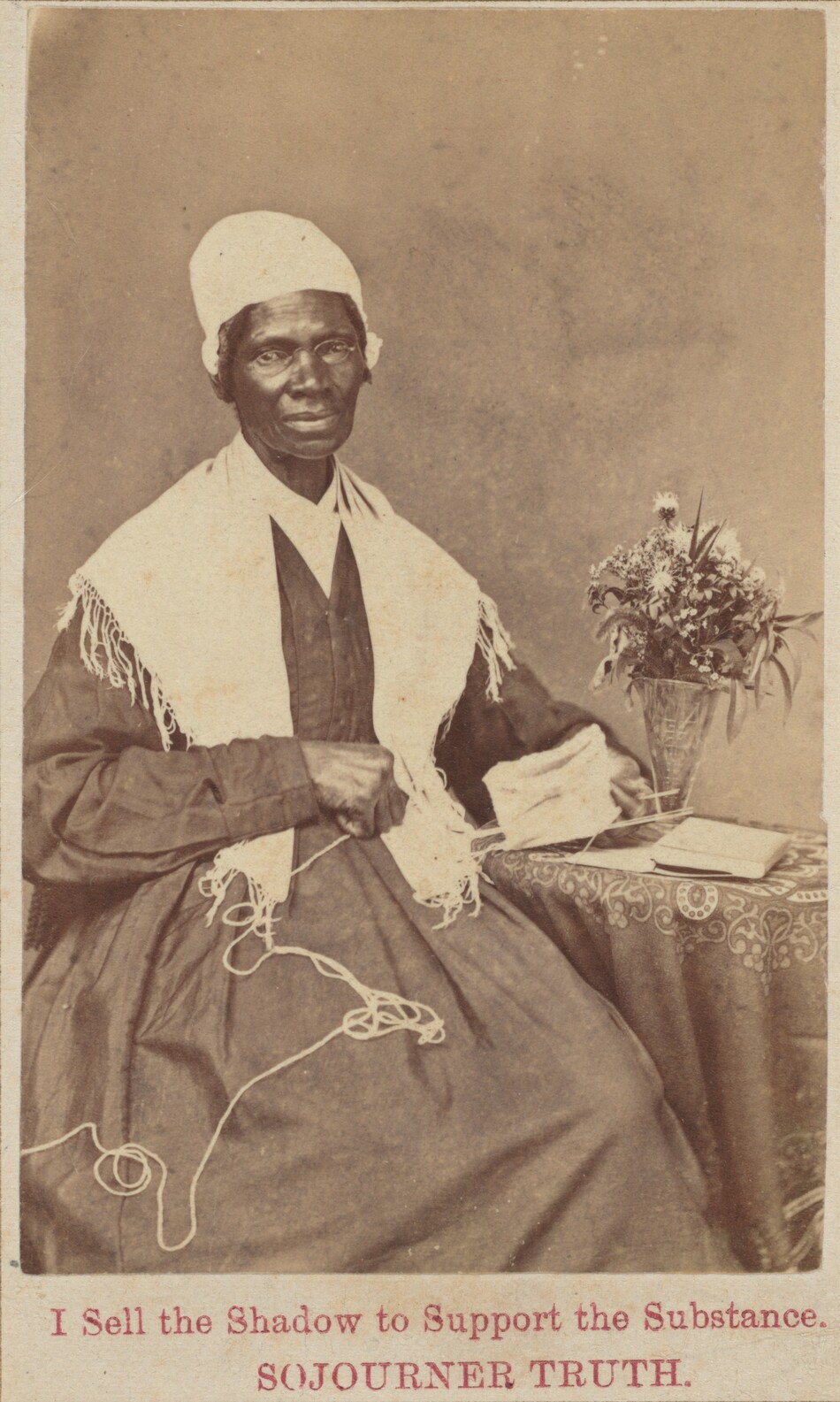

From the 19th century onward, new technology, the expansion of the country, and vast social and political change spurred artists to embrace modern media, like photography, as well as novel approaches predicated on changes in the relationship between the artist and subject. This shifting dynamic is seen in two of George Catlin’s portraits of American Indians, The Female Eagle—Shawano, 1830, and Boy Chief—Ojibbeway, 1843. Catlin portrayed these individuals because of his personal interest in what he saw as the disappearance of Native culture and his drive to document it, rather than commercial motives. Meanwhile, the advent of photography introduced inexpensive prints that were traded and collected in the first photo albums. These included images of people of different social classes and portrayals of individuals who embodied certain ideals, such as a portrait of abolitionist and activist Sojourner Truth, 1864. She included a caption for her portrait, “I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance,” indicating that she marketed her image in order to promote her beliefs.

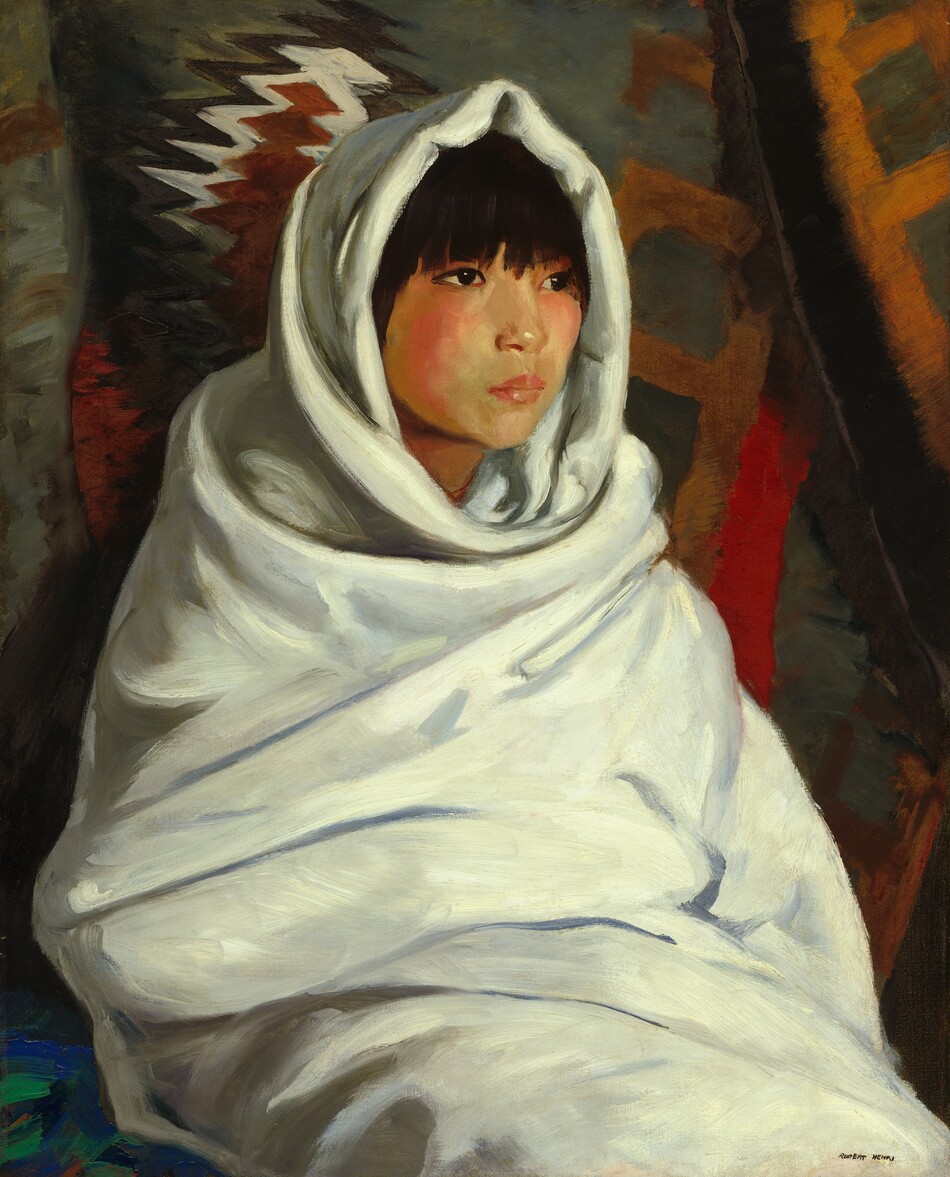

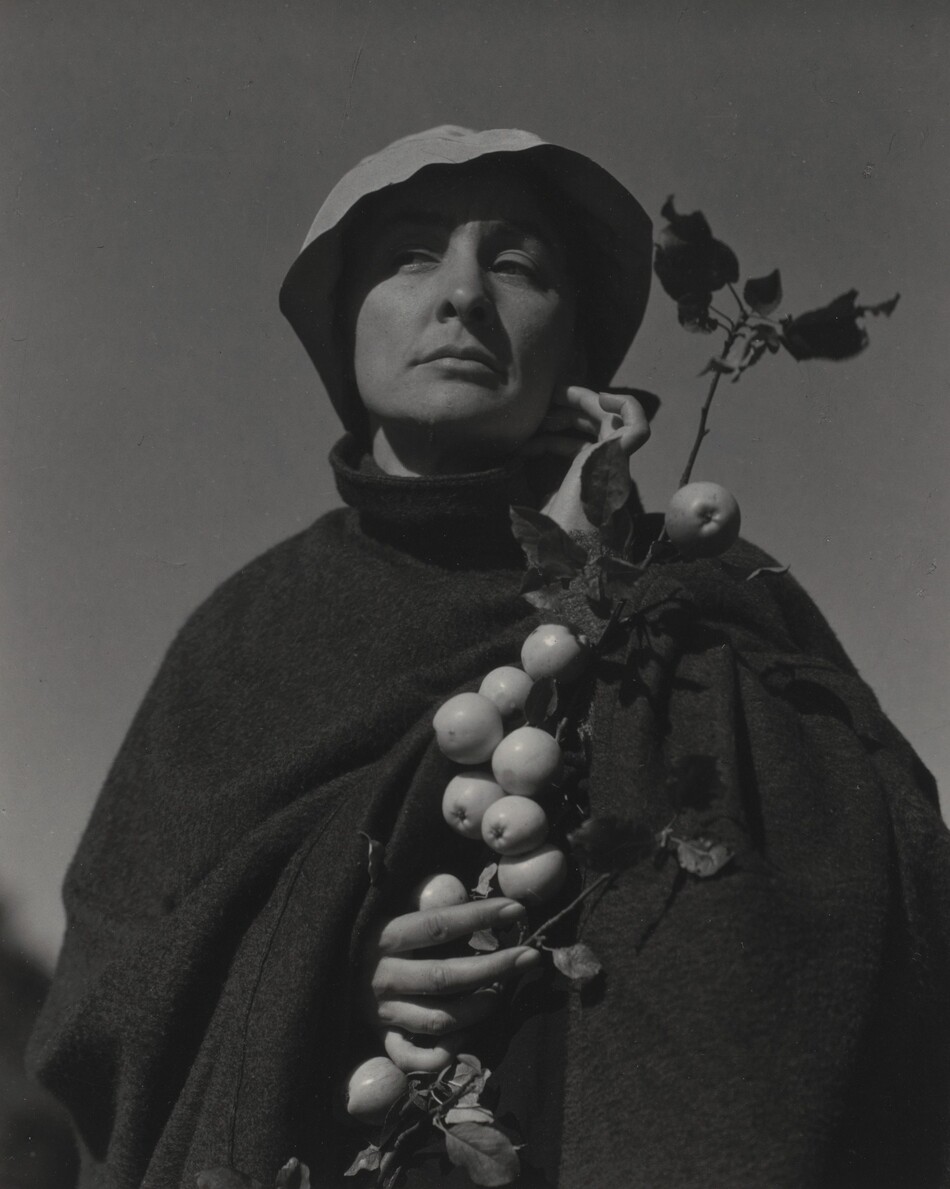

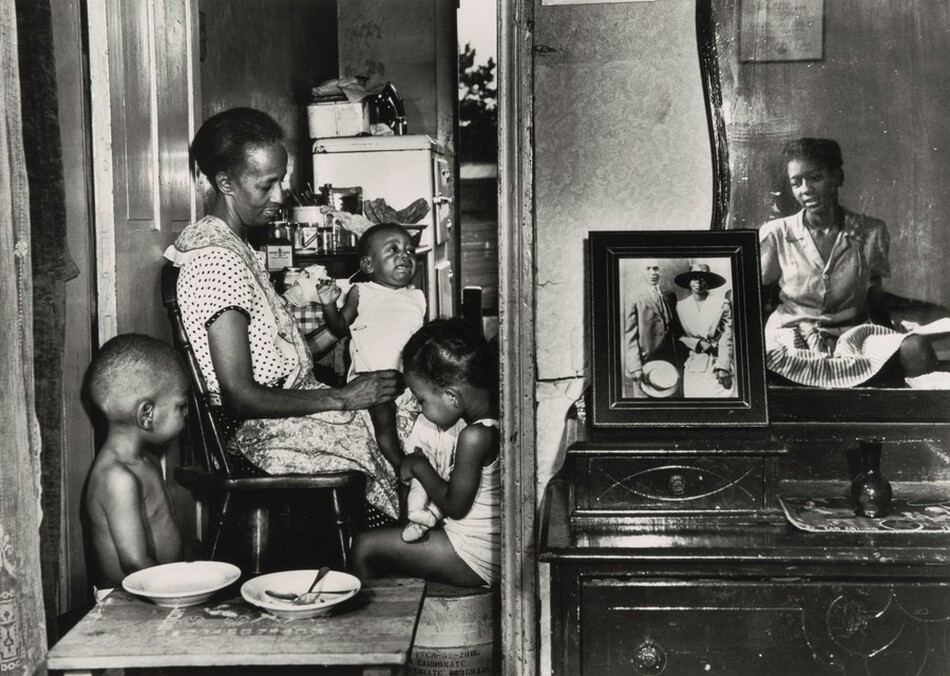

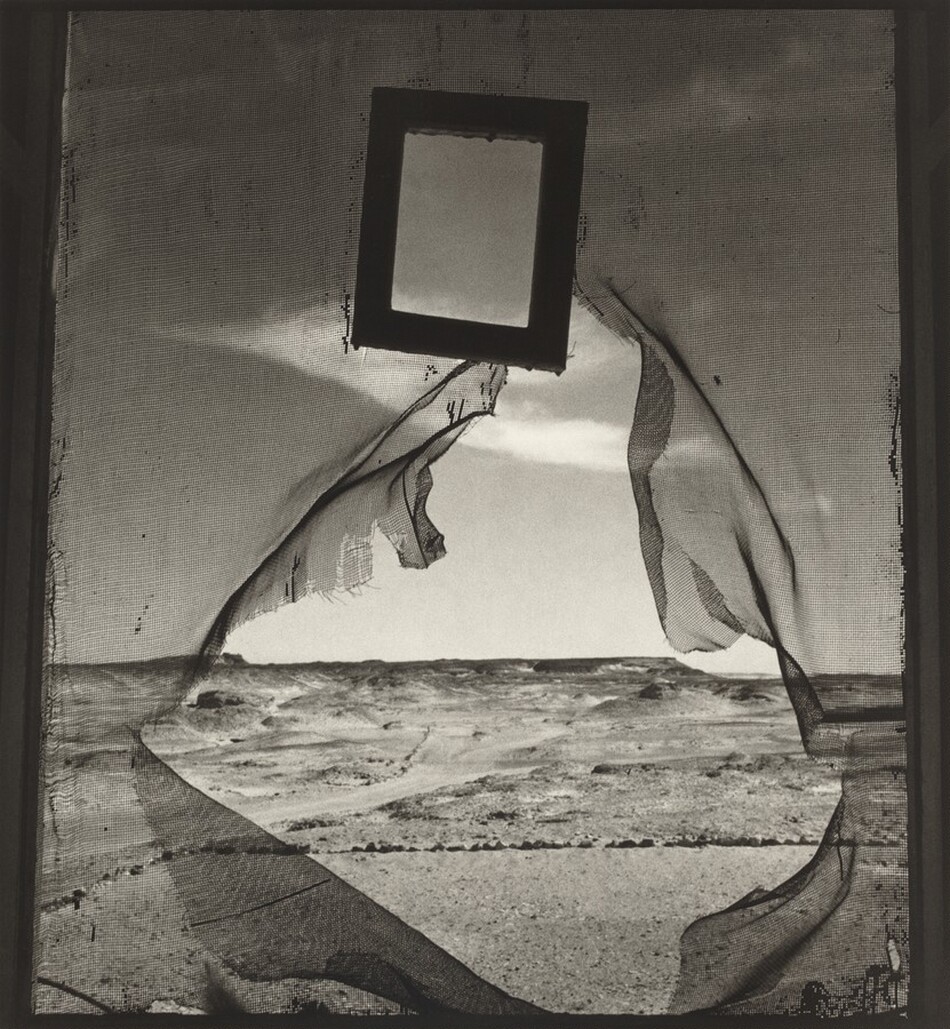

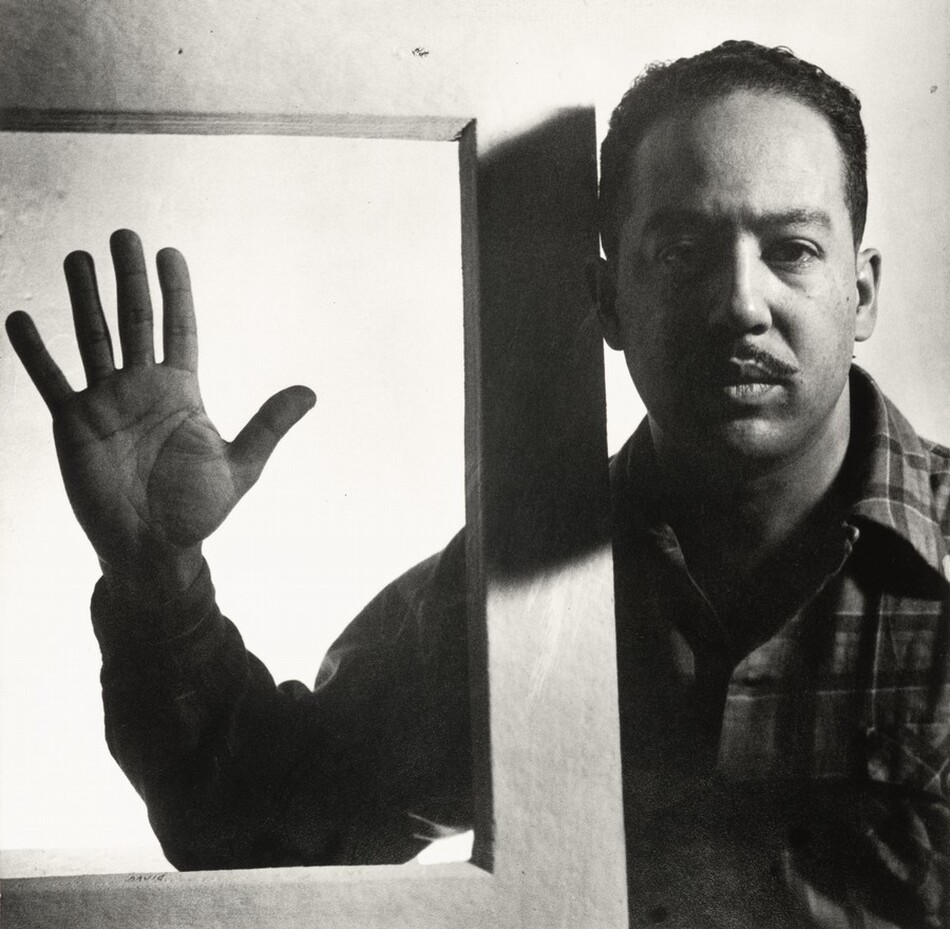

Artists of the 20th century continued to extend the purposes of portraiture. James Van Der Zee opened a photography studio in Harlem and extensively documented the lives of African Americans during the Harlem Renaissance, yielding an important chronicle of the period, including Sisters of 1926. Other images, such as Georgia O’Keeffe, 1924, a photograph of the painter captured by her partner Alfred Stieglitz, reflect the American ethos of individualism. In Little Girl in White (Queenie Burnett), 1907, painter George Bellows brought attention to the lives of marginalized street children in an era before child labor laws protected them. Compare Bellows’s work with that of John Singer Sargent’s Miss Beatrice Townsend, 1882, of a generation earlier; the two girls embody great contrasts in American society. Other artists chose to explore the properties of portraiture and perhaps the limitations of representation, such as Lee Miller in her Portrait of Space, near Siwa, Egypt, 1937.

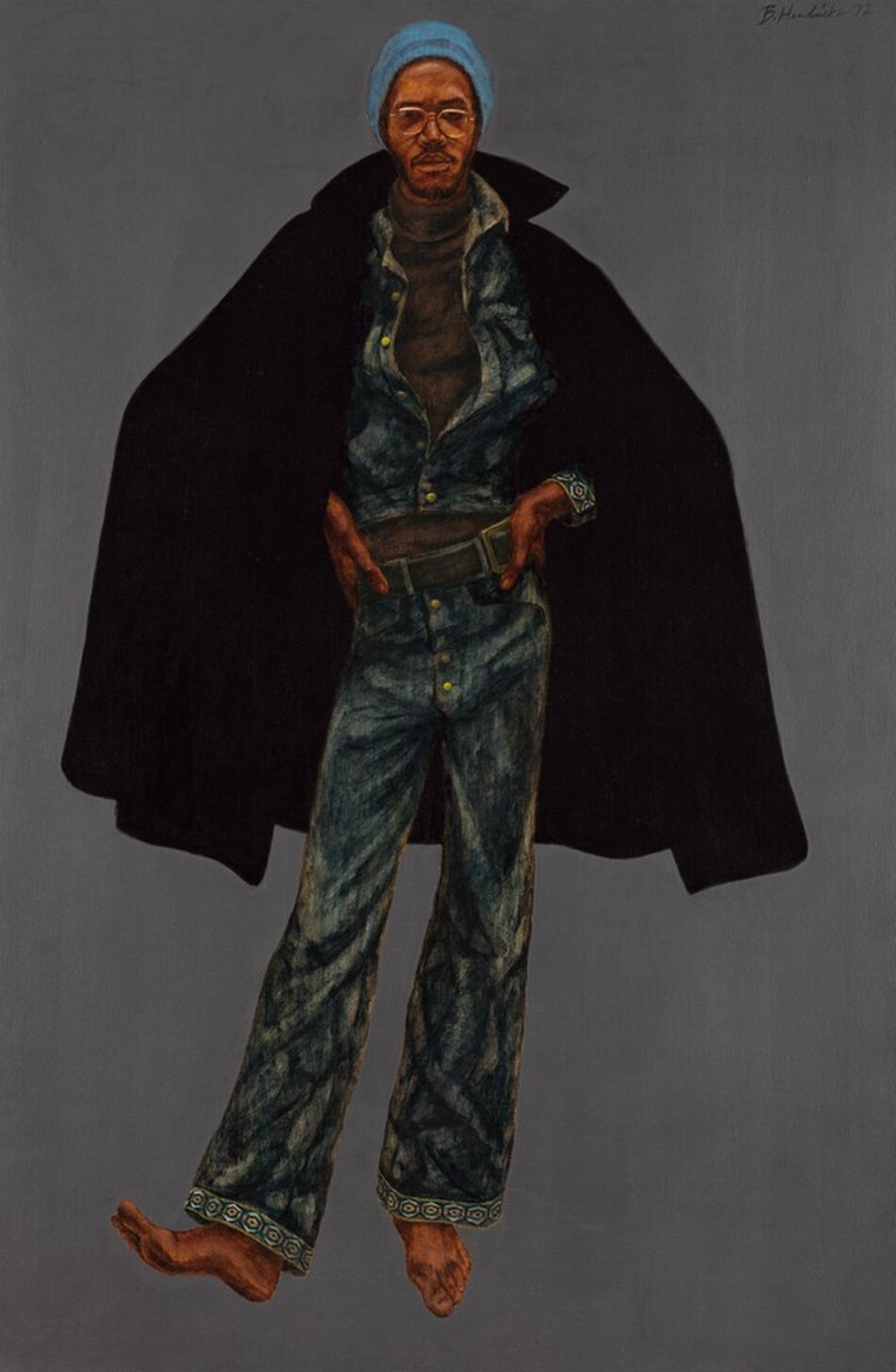

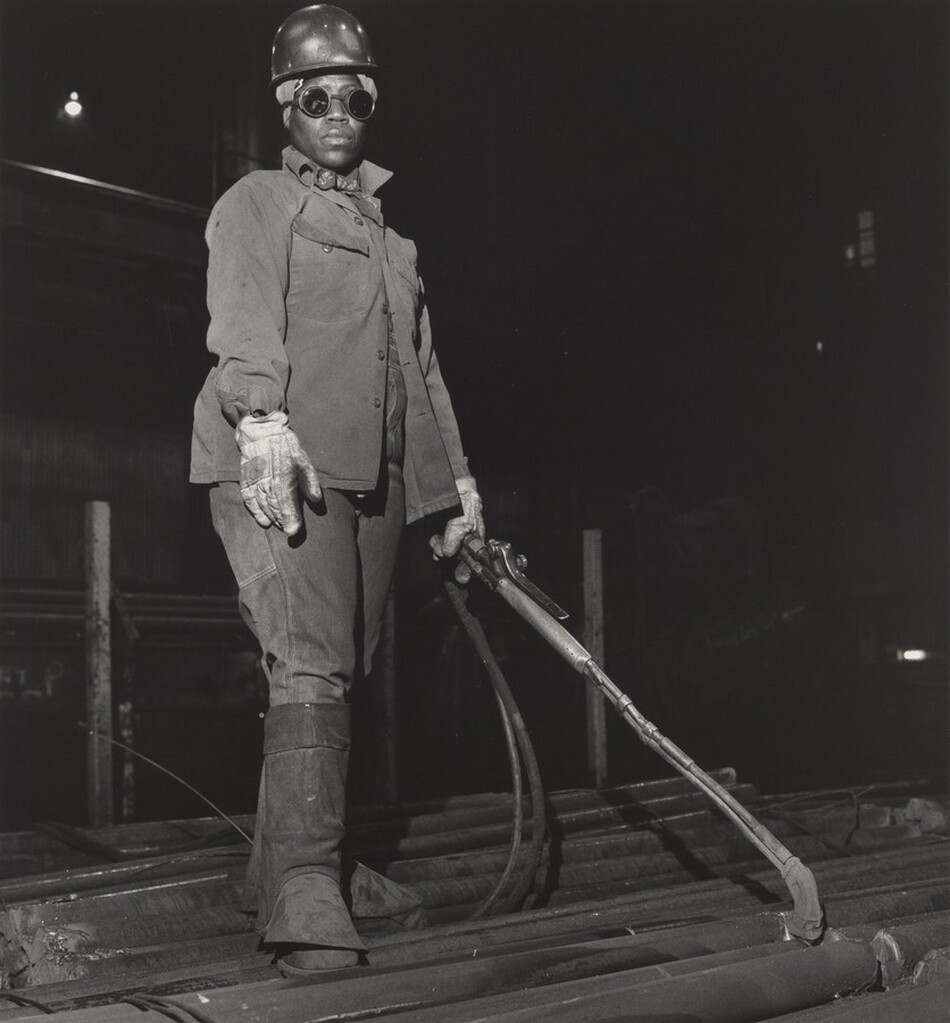

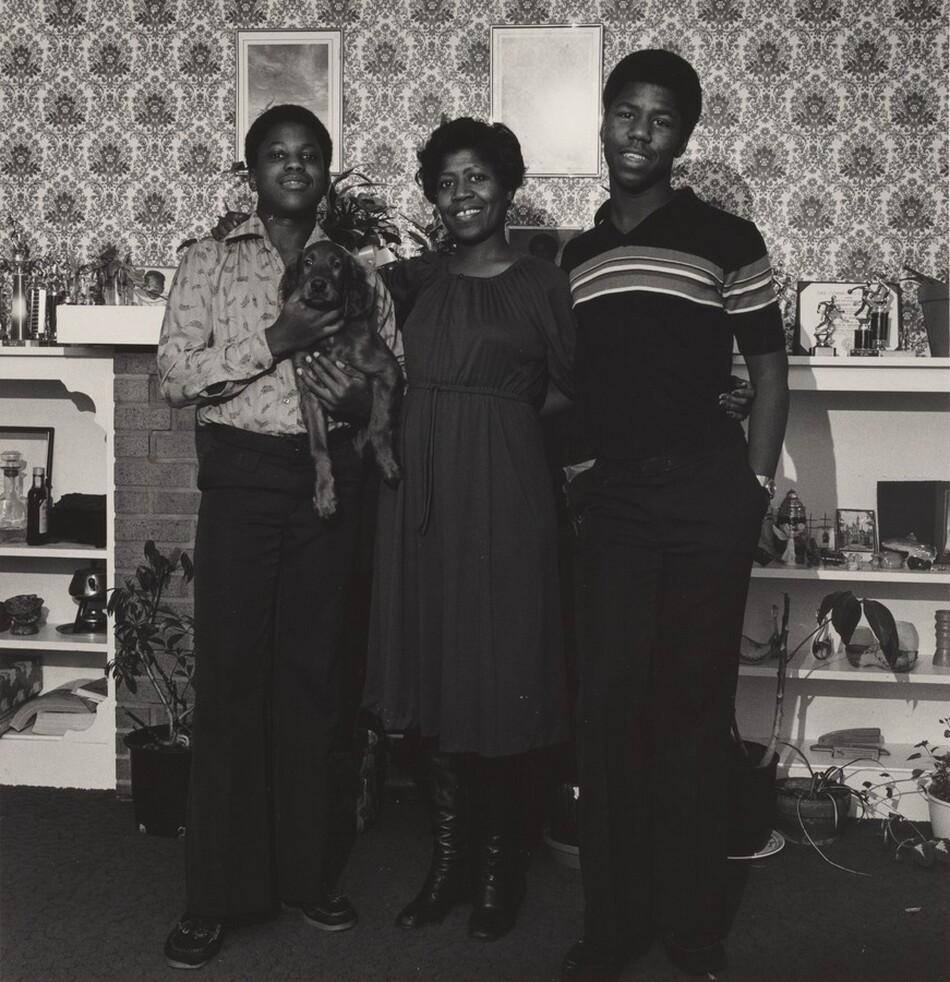

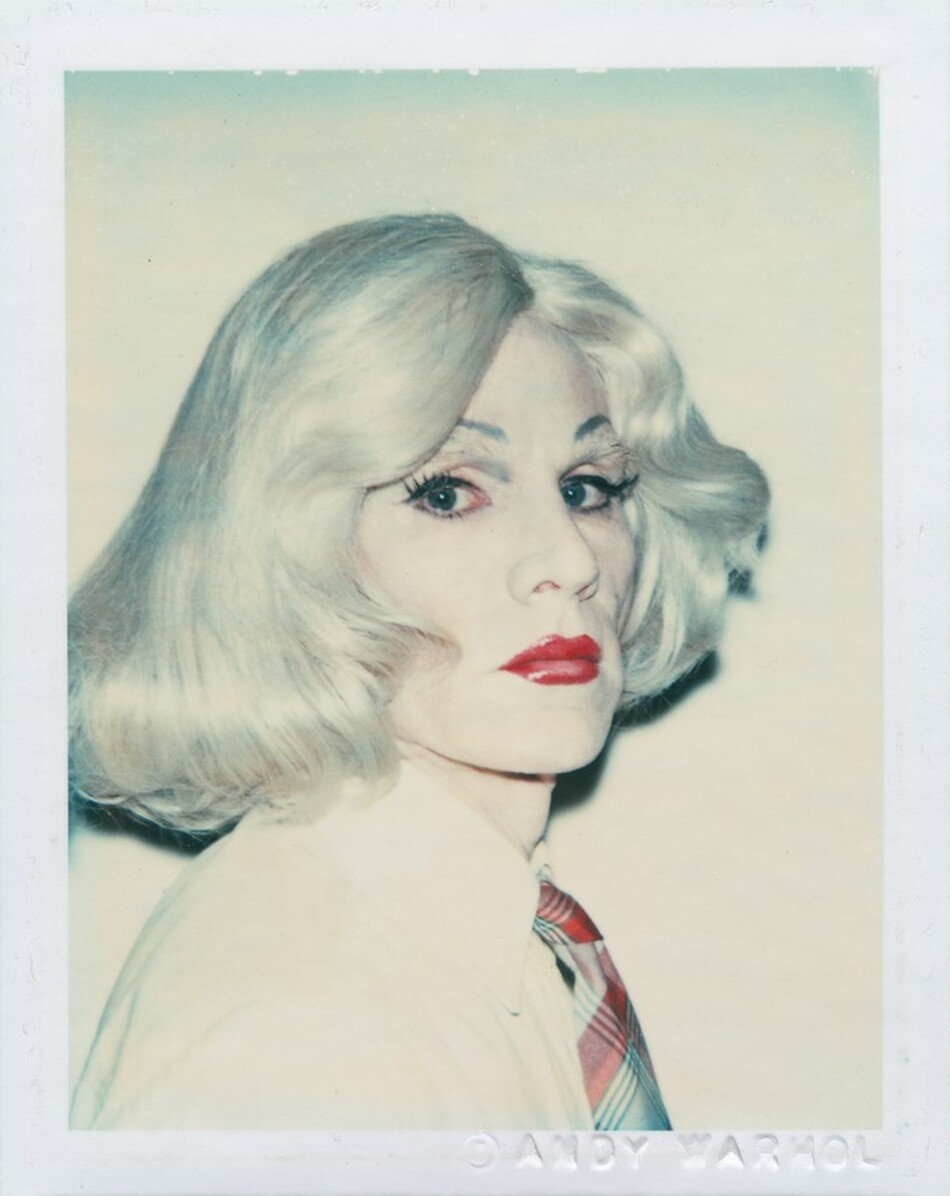

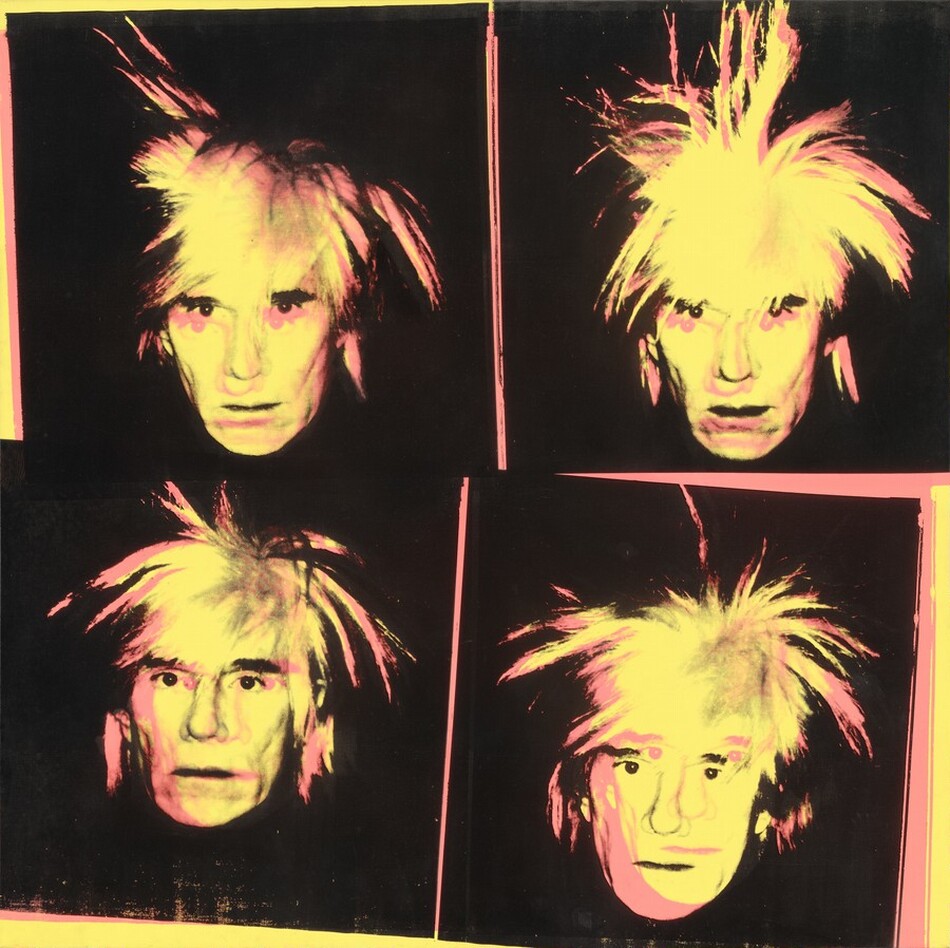

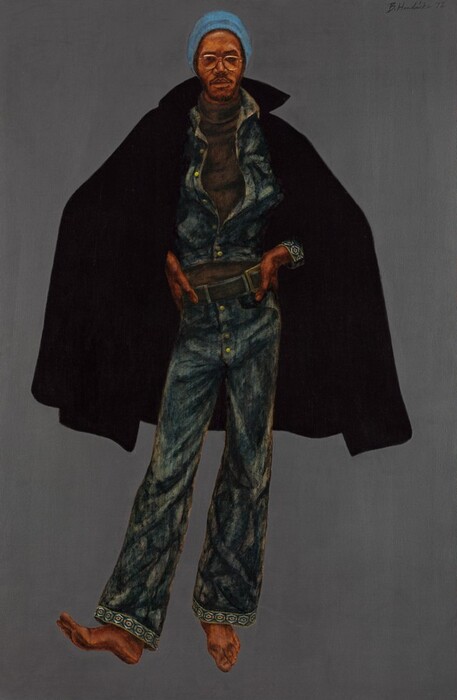

The trajectory of experimentation continues as the boundaries of the genre of portraiture extend yet further. Contemporary portraits depict not only the visible signs of a person’s identity and appearance, but also reveal other ways in which we define ourselves: fitting in or being at odds, connections to place/home/community, and identification with work/civic/personal life. In his Working People series (1972–1987), photographer Milton Rogovin documents working-class people employed in trades and factories in rural America. Barkley Leonnard Hendricks and Andy Warhol explore fashion and self-presentation (George Jules Taylor, 1972, and two Warhol self-portraits of the 1980s) and the myriad ways in which identity and appearance may shift.

How we picture and understand ourselves through portraiture continues to evolve as artists and their sitters explore new forms and approaches to representation and identity.

Selected Works

Quotes

“A man has as many social selves as there are individuals who recognize him and carry an image of him in their mind.” —William James, 1890

“From long experience, I know that resemblance in a portrait is essential; but no fault will be found with the artist (at least by the sitter), if he improves the general appearance.” —Thomas Sully, Hints to Young Painters, 1873

“It will soon be. . .difficult to find a man who has not his likeness done by the sun. . . . the immortality of this generation is as sure, at least, as the duration of a metallic plate.” —Brother Jonathan (a 19th-century periodical based in New York) on the popularity of daguerreotype portraits, which were produced on metallic plates, 1843

“A portrait is not a likeness. The moment an emotion or fact is transformed into a photograph it is no longer a fact but an opinion. There is no such thing as inaccuracy in a photograph. All photographs are accurate. None of them is the truth.” —Richard Avedon, 1985

“Ultimately, having an experience becomes identical with taking a photograph of it.” —Susan Sontag, On Photography, 1977

Activity: Reading Visual Cues in Portraits

Portraits can embody a surprising number of qualities that range from the impersonal and public (status, profession, or group identity) to very individual characteristics (appearance, expression, or gender). Artists and their sitters use portraits to convey a particular impression, such as turning your “good side” to the camera, trying to appear serious, or focusing attention on a particular social issue.

Choose several portraits from the image set or Pinterest board. Discuss what you think the people pictured are trying to say about themselves and who they are through their portraits.

Research and select several contemporary images of public figures. These could be celebrities, politicians, or activists, to name a few examples. What do you think each person is trying to communicate through his or her self-presentation? Can you find another likeness of that same person that either supports your image or contradicts it?

Activity: Respond and Related

Examine the image set. Try to place the works in chronological order. Discuss the ways in which you can see the art of portraying people changing over time. Think about who is pictured and how they are represented.

Activity: We Are Family

Find images of families (however you define “family”) in the image set. Explore what the portraits tell you about the relationships among the sitters and who they are. Examine the qualities of the individuals, but also how people are grouped together (posed or unposed); the setting in which they are placed (inside or outside, home or work); and the objects, if any, in the pictures. Why are the artist’s choices important?

You can perform this exercise with different groupings of sitters: women, men, children, and people of color, for instance.

Activity: Explore Portable Portraits

Smartphones allow us to keep images of ourselves, friends, and family within reach of us so that we can look at them or show them to others anytime. This is not a new idea. During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, artists painted portable miniature portraits that the owner (or wearer) could keep close in a similar way. These small likenesses were considered fine art—they were commissioned just like large portraits, and therefore were only available to people who could afford the expense. You can see images of a woman wearing portrait miniatures and an artist painting one on the associated Pinterest board.

Another form of portable portrait was the carte-de-visite, which means “calling card” in French. It was invented in France in the 1850s and found its way to the United States quickly. Bearing your portrait, as well as your name and address, cartes-de-visite were the first inexpensive, mainstream form of photography. They supplanted the popular, but more expensive, daguerreotypes (see Augustus Washington’s Portrait of a Woman in this set), which were also sometimes carried as personal mementos. A craze in calling cards consumed Americans in the early 1860s: people traded them, compiled albums, and even collected images of celebrities and notable personages, like Sojourner Truth, who sold cartes-de-visite to raise money.

Consider the functions of these two kinds of portable portraits alongside the ones on your phone now. Respond and discuss:

- What is each kind of picture for—miniatures, calling cards, and pictures on your phone?

- What is its value (personal, commercial, monetary) and why?

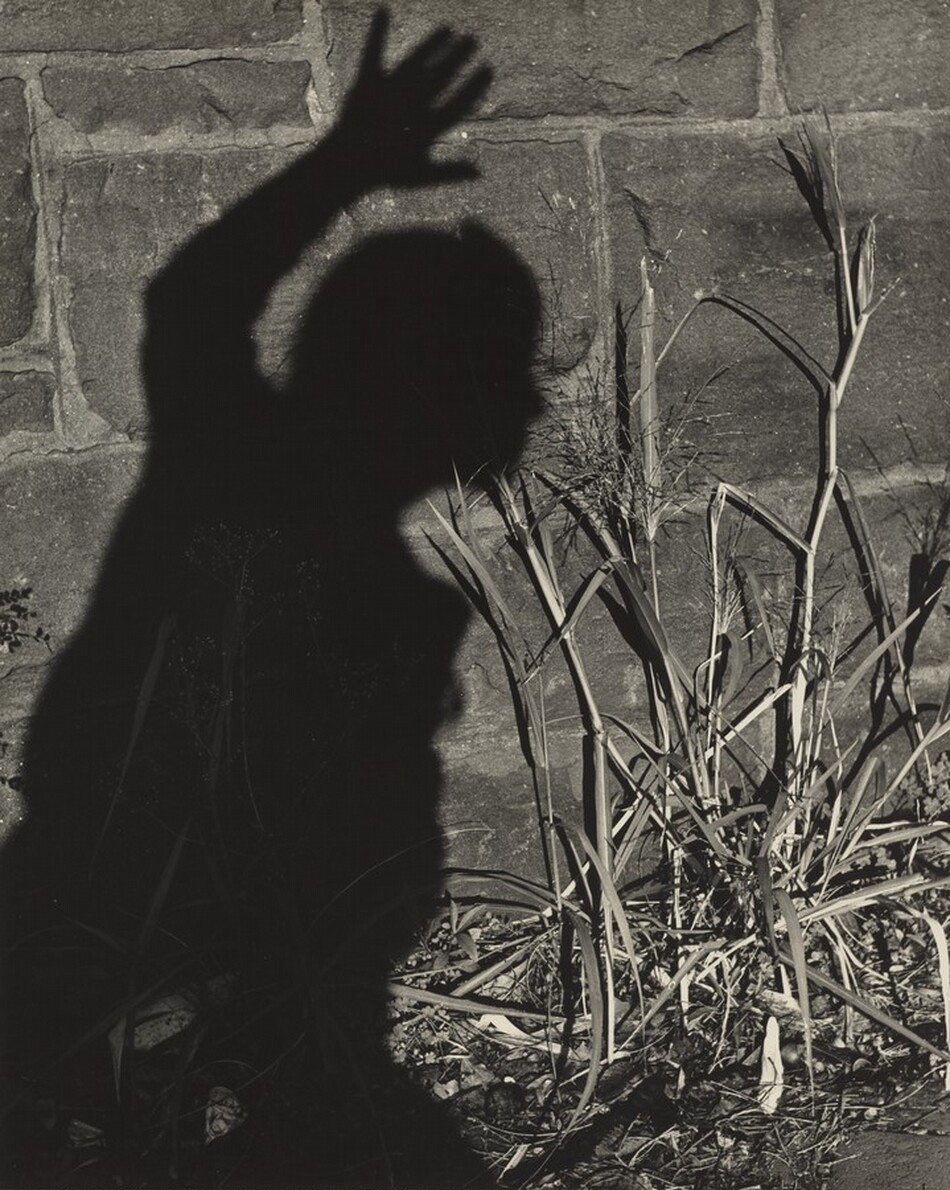

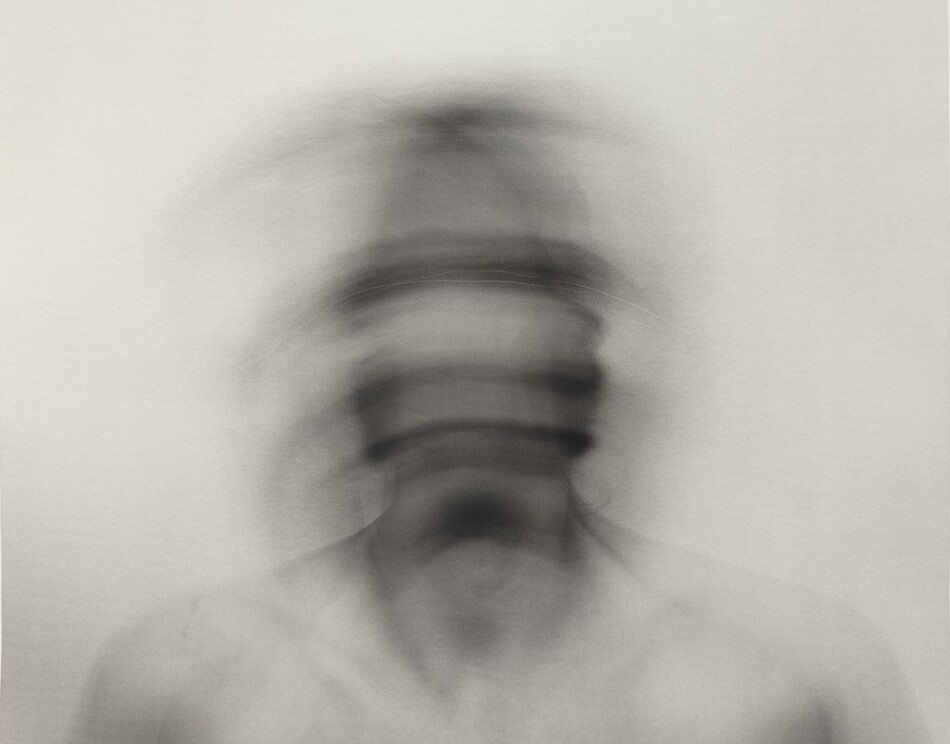

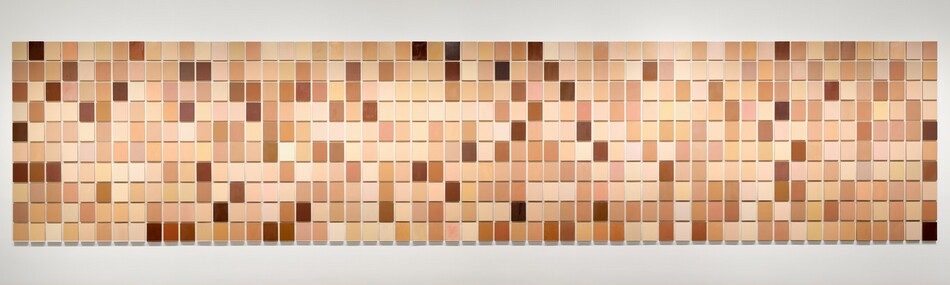

Activity: Alternative Portraits

These pictures may be different from what you would normally think of as a portrait. How and why are they different? In what ways can they still be defined as portraits?

Activity: Showing Yourself

Pictures capture the dimensions that each person expresses in different combinations and in distinct ways. This activity is designed to explore the ways you present yourself in various situations.

Collect five pictures of yourself in scenarios from daily life—think about the different settings, occasions, and people with whom these moments are recorded. Print out the images or create a slideshow on your phone or computer. Do you think that one picture is closer to who you are than the others? Did any of the images show you something unexpected about yourself?

Additional Resources

Picturing America educator resource, National Endowment for the Humanities

George Catlin, Catlin’s Indian cartoons. Synopsis of the Author’s roamings in gathering the paintings enumerated in his Catalogue, [1972]

Richard H. Saunders, American Faces: A Cultural History of Portraiture and Identity (Lebanon, NH, 2016)

John Walker, Portraits: 5,000 Years (New York, 1983)

Shearer West, Portraiture (Oxford, 2004)

You may also like

Educational Resource: Harlem Renaissance

How do visual artists of the Harlem Renaissance explore black identity and political empowerment? How does visual art of the Harlem Renaissance relate to current-day events and issues? How do migration and displacement influence cultural production?

Educational Resource: Manifest Destiny and the West

When you think about the US West, what images and stories come to mind?