The Key Set: 1918–1937

Publication History

Published online

Alfred Stieglitz, Music—A Sequence of Ten Cloud Photographs, No. V, 1922, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.833

Key Set number 797

Alfred Stieglitz, Music—A Sequence of Ten Cloud Photographs, No. V, 1922, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.833

Key Set number 797

The years from 1918, when Georgia O’Keeffe moved to New York, until 1937, when Stieglitz put his cameras away because of poor health, were the most prolific ones in his life. He saved more than 1,110 photographs from these years that are now in the Key Set. Certainly, he had more time: after 291 closed in 1917 he did not open another gallery until 1925. But his burst of creativity cannot be attributed only to his new-found freedom. For almost the first time in his career he stopped synthesizing the art and ideas of others and began to photograph out of an intense need to express himself. Perhaps as a consequence, he ventured into areas where he had few if any models. O’Keeffe inspired in him a creative passion—and simply a passion—he had never known before: he made more than 100 studies of her in the first two years they lived together. But he soon applied the lessons he learned from photographing her to a broader investigation. His work from this period is about many things—his understanding of women, the need to create a uniquely American art, the relationship of abstraction to photography, the viability of the modern American city, and the ability to derive strength from the humble American landscape—but it is unified by his fascination with multiplicity, time, and change as ways to arrive at a fuller understanding of these concepts. Once again, he used his one-person shows—mounted first in borrowed space in the early 1920s, and later at his galleries, the Intimate Gallery, 1925–1929, and An American Place, 1929–1946—as vehicles to clarify his ideas and as springboards to new ones. As a result of the rigorous self-scrutiny his shows afforded him, his photographs changed profoundly from the didactic, analytical, and often polemical depictions he made before the war to more experiential and intuitive ones, deeper, richer, and more complex, and layered with emotional resonance and personal meaning.

Almost as soon as O’Keeffe arrived in New York from Texas on 9 June 1918 Stieglitz began photographing her with what she later described as “a kind of heat and excitement.” For many years he had been intrigued with the idea of using photography as a way to explore and articulate his understanding of womanhood. He did so not only in Sun Rays—Paula, Berlin where, in the background, multiple portraits of Paula surround a picture of himself, but also in another patently autobiographical photograph, My Room, made in New York in the early 1890s (fig. 1). Using his room as a stage, as he would later use 291, he placed numerous photographs, reproductions of paintings, and a few original paintings on the floor, walls, and mantel. Portraits of his mother and father are prominently displayed, but all the rest are pictures of women: including his own photograph of Maria, Bellagio, a reproduction of Rubens’ Helena Fourment, and an unidentified reproduction of a nude (Key Set number 34 and fig. 2).

Figure 1

Alfred Stieglitz, My Room (Studio), 14 East 60th Street, 1891, lantern slide, location unknown

Figure 1

Alfred Stieglitz, My Room (Studio), 14 East 60th Street, 1891, lantern slide, location unknown

On a clipboard are many other pictures, possibly of actresses, models, or friends, that are identical or closely resemble one another, suggesting his fascination with the ways photography could create multiple, if only slightly different depictions of a person or thing. By presenting women as innocent children, seductive maidens, and mothers, Stieglitz revealed not only a youthful fascination with the opposite sex, but also his recognition that through a kind of photographic collage he could join disparate images to address a larger idea than could be revealed in any single work. His composite portrait of Kitty from the turn of the century extended this idea to include many pictures of her made over several years and in a variety of activities. Yet both My Room and his collective portrait of Kitty were too intensely personal, sometimes too banal, to form works of art with universal appeal. That would not be a problem with O’Keeffe.

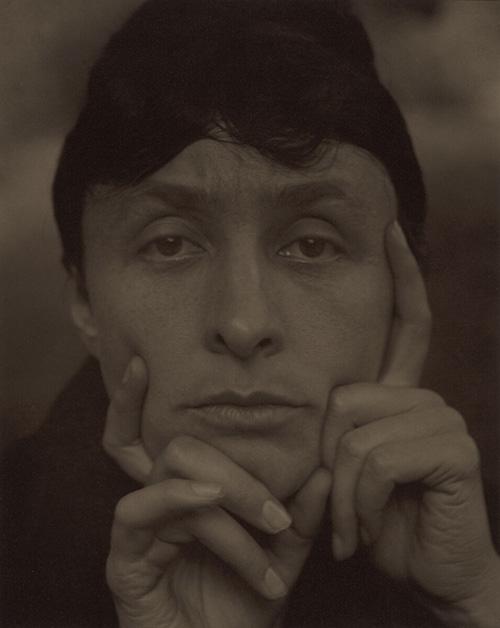

In less than eight weeks before they left for Lake George in August 1918, Stieglitz made more than fifty studies of O’Keeffe, a prodigious number for a photographer who had averaged little more than a dozen finished works per year for the last decade (Key Set numbers 471–529). These portraits from their first summer in New York reflect their growing closeness and O’Keeffe’s increasing comfort at being the object of such concentrated scrutiny. But they also show Stieglitz’s mounting fascination with seriality and the possibility of photographing the same subject day after day, often in only slightly different poses, mining each arrangement and expression for its greatest potency. In many of the first studies, made most likely before he separated from his wife Emmy and before Stieglitz and O’Keeffe began living together in July 1918, O’Keeffe looks off to the side, as if she is uncertain of her ability to maintain steady eye contact with the camera or with the photographer himself for an extended period of time. As in his earlier studies of her from 1917, he posed her in front of her art; for example, positioning her head so that it was perfectly contained within the ovoid form of her drawing of the Palo Duro Canyon in Texas; or posing her hands to hold a button on her coat, repeating the forms bubbling up from the canyon floor (Key Set numbers 480 and 474). As their intimacy grew, so too did his ability to conjoin the artist and her art, and he began to suggest, far more explicitly than he had done in the past, that O’Keeffe’s body and art were one. Radically cropping his compositions, he positioned her head, arms, and hands against empty pieces of paper so that their forms not only mirror those in her charcoal drawing, but merge with it to become elements in her composition (Key Set number 490). In one study he made her charcoal drawing appear to spring forth from the crown of her head as the manifestation of creative invention (Key Set number 493).

Figure 2

Peter Paul Rubens, Helena Fourment, 1636/1638, oil on oak panel, Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Gemäldegalerie. © KHM-Museumsverband

As his studies of her evolved, they became less about O’Keeffe as an artist and more about her as a woman and lover, and of the sexual passion they shared. Often clad only in her loosely draped kimono and posed in front of an empty wall, O’Keeffe looks directly at the camera—that is, at Stieglitz—often with a palpable sense of passion and longing (Key Set numbers 499–502). He photographed her like the lover that he was, entranced with every inch of his beloved, but also studied her like a painter or sculptor analyzing every inch of a model’s body to understand how to portray the whole more accurately, as, for example, Rodin did. He photographed parts of her body—her torso, legs, feet, and hands (Key Set numbers 508–516 and 523–529). And, as Rodin did, he recognized that these fragmentations could stand as independent studies, expressive of his understanding of O’Keeffe’s personality.

At Lake George in the summer of 1918 when they were constrained somewhat by his family, her hands became the most expressive element in his compositions. Frequently he depicted her wearing his signature black cape, often with her hands pulling the collar tightly around her neck and face, as if using his persona to shield her from the outside world (Key Set numbers 534 and 535). Often too he photographed only her pale fingers emerging from his cape, cut off from the rest of her body, and delicately caressing the folds (Key Set numbers 531–533). By making the photographs so sharp that the pores in her skin are visible, he stressed the physicality of the images themselves. Matching the mood of the images to his choice of photographic paper, he used platinum paper for his small studies of O’Keeffe’s hands because its delicate but obvious texture reflected the sense of touch in the works, and palladium paper for his large 8 × 10-inch studies of her nude or wearing only her kimono, because its rich brown tones, smoother surface, and lustrous highlights corresponded with the sensuous, often brooding quality of his imagery.

In 1919 O’Keeffe’s hands continued to be Stieglitz’s primary focus. In several photographs, they are posed in front of her face, as if she were a dancer frozen in mid-step, but in others they delicately stroke one another or rest on her chest, evoking a highly charged sense of touch (see Key Set numbers 562–565 and 576). In many, though, her hands are so detached from the rest of her body or perform gestures so different from the way a woman normally touches herself, they rise from individuality to generality to suggest, as Stieglitz’s friend Lewis Mumford wrote in 1934, that these photographs were “the exact visual equivalent of the report of the hand or face as it travels over the body of the beloved,” translating “the unseen world of tactile values as they develop between lovers not merely in the sexual act but in the entire relationship of two personalities” (see Key Set numbers 576 and 578–581).

In 1921, after finding it difficult to “add” anything more to his portraits of her in 1920, Stieglitz showed more than forty photographs of O’Keeffe in a one-person exhibition at the Anderson Galleries. Instead of exhibiting the photographs singly, he grouped them into clusters: eight studies were titled Hands (One Portrait), 1918–1920, three Feet (One Portrait), 1918–1920, three Hands and Breasts (One Portrait), 1918–1920, and three Torsos (One Portrait), 1918–1920, along with twenty-five titled A Woman (One Portrait), 1918–1920. He called the photographs “A Demonstration of Portraiture,” designed to show the “interrelationship of the parts to the whole” and form a composite whole—One Portrait—that addressed a larger idea than could be embodied in any single photograph.

But what was this composite whole Stieglitz wished us to see? Was it to be understood as a study of O’Keeffe’s personality, as some of her biographers have maintained? If so, Stieglitz’s portrait does not match the person revealed in her letters, which show her to be spontaneous, with a quick and wry sense of humor, whose sexuality was frank and earthy, not seething as Stieglitz depicted it. Because it included works made over several years, was the composite portrait intended to provide an almost cinematic record of O’Keeffe’s life, showing her at all times of the day and in varying activities, as he had earlier depicted Kitty in his photographs titled Morning, Noon, and Night? If so, then why are there so few pictures of her painting or doing the mundane chores that we know she did, and why is the mood so limited? While Stieglitz made more than 140 photographs of O’Keeffe in their first three years together—the period when he most actively recorded her—the temper of the photographs in the Key Set does not range widely. O’Keeffe smiles or frolics with friends at Lake George in only a few studies (Key Set numbers 628–632 and 634). Occasionally he photographed her with an air of childlike innocence and purity or as a frail creature in need of protection, but the O’Keeffe who emerges from the portraits in the Key Set made between 1918 and 1921 is primarily a strong, powerful, and extremely sensual woman (Key Set numbers 499–502). Were these photographs, as some scholars—especially those more interested in O’Keeffe’s art than Stieglitz’s—have concluded, a collaboration between the two artists and was the goal of this “creative affiliation . . . the ongoing definition of . . . O’Keeffe’s femininity”?

To be sure, a photographic portrait made with a large 8 × 10-inch camera, with its cumbersome set-up, use of umbrellas to reflect the light, and a long exposure time, requires a different kind of collaboration from painting or sculpture. A subtle change of expression, a slight movement in posture, even a shift of the eyes can alter the result. Obviously, O’Keeffe willingly held the poses and the expressions, and especially in the early years of their relationship, as she later stated, she was not only “flattered” by his attention, but deeply in love with him and as supportive of his art as he was of hers. Yet, in later years she distanced herself from the photographs. In 1978, she wrote, “when I look over the photographs Stieglitz took of me, I wonder who the person is.” Noting that “Stieglitz had a very sharp eye for what he wanted to say with the camera,” she continued, “I was asked to move my hands in many different ways—also my head—and I had to turn this way and that. There were nudes that might have been of several different people—sitting—standing—even standing on a radiator against the window.” With her dry wit, she added, “That was difficult—radiators don’t intend you to stand on them!” When asked if she collaborated with Stieglitz, she replied, “You had to collaborate . . . You had to sit there and you had to do what you were told.” And, when asked specifically if the creation of this massive composite portrait, which totaled 331 photographs by the time it was completed in the 1930s, was something she wanted to do, O’Keeffe emphatically replied, “It was something he wanted to do.”

While these comments were made years after the project was completed, and years after Stieglitz’s death, other evidence suggests that this was wholly his project. First, he repeatedly derived the poses and compositions from the art he had exhibited, collected, and lived with for many years. He looked to Rubens’ Helena Fourment and the watercolor washes by Rodin that he had shown at 291 when he depicted O’Keeffe in a loosely flowing kimono; he recalled the Franz von Stuck reproduction of Sin that he had owned for several years when he recorded her erect stance, half-lowered eyes, and bare breasts; he echoed the Matisse lithographs he had exhibited at 291 when he photographed her full breasts and pubic hair; he alluded to Brancusi’s Sleeping Muse I that he had shown at 291 when he focused on the simplified form and outline of her head as she was lying down; and he evoked the iconic power of the African sculptures he had exhibited at 291 when he photographed her hands holding her face as though it were a mask (figs. 3–8).

He also controlled the look of the photographs in the darkroom, by cropping them, choosing what kinds of prints to make—soft, charcoal platinum prints; rich, brown palladium prints; or cool gelatin silver prints—what areas to highlight and to suppress, and how to tone them. And, of greatest importance, he made the final determination of which photographs to save for his collection. Especially during the early years of their relationship, he chose not to save many of the more casual pictures of her, such as Georgia O’Keeffe, Fred and Ella Varnum, and Bly with “Judith,” Lake George, 1920, that show the more spontaneous and relaxed woman at work and at play.

In the catalogue essay for an exhibition of these photographs of herself in 1978, O’Keeffe concluded, as had critics in the 1920s, that Stieglitz “was always photographing himself.” She recognized that his portraits of her expressed not just his love for her, but his vision of her and of their relationship and how she embodied his understanding of woman in a more universal sense. Stieglitz himself made this perfectly clear in his 1921 exhibition. Although all of the other portraits’ subjects were identified by name, the forty-five studies of O’Keeffe were simply titled A Woman (One Portrait) or Hands (One Portrait). Stieglitz’s vision of O’Keeffe was steeped and shaped by the late nineteenth-century conception of woman as part child and part temptress—he repeatedly referred to her as “the Great Child” and “the Woman unafraid”—as well as by Rodin’s idea of the “Woman Supreme,” Henri Bergson’s concept of élan vitale, the powerful and sexually ambiguous imagery of D. H. Lawrence, and, of course, by Sigmund Freud, Havelock Ellis, and Edward Carpenter. Stieglitz’s understanding of this larger concept of woman and his feelings for O’Keeffe more specifically are seen in his celebration of the beauty of every facet of O’Keeffe’s body and in his sensual depiction of its texture, smoothness, and suppleness. These are photographs that speak about the intoxicating desire Stieglitz felt for O’Keeffe, the allure of her physical presence, and the profound, palpable impact that one person can have on another.

Stieglitz’s photographs of O’Keeffe formed the core of his 1921 exhibition at the Anderson Galleries, but the show, in addition to including portraits from throughout his career, also presented more than twenty-five studies of family and friends and signaled the direction for his work in the next two years. Although the 1921 checklist divided the photographs into portraits of “Men” and “Women,” after his experiences with the artist/woman/lover O’Keeffe, he now used a similar approach for both sexes. As he had done with O’Keeffe, he placed his camera extremely close to his subjects and focused primarily on their heads, often investigating the same visual effects. Intrigued by the abstract patterning of light seen in glass or mirrors, he positioned both O’Keeffe and Margaret Treadwell in front of the glass door at the Lake George farmhouse in the summer of 1921 and posed both Marin and the critic Herbert Seligmann in front of mirrors, probing how he could merge and activate background and foreground by echoing the shapes of their face, hair, arms, shoulders, and clothing in their reflections (Key Set numbers 683–689 and 704–705). When he made a number of portraits, he often progressed from more formal studies of his sitter’s face and shoulders to more intimate ones (and if the subject was a woman, occasionally from fully clothed to less clothed) to details of hands, legs, or feet, as he had with O’Keeffe (Key Set numbers 711–714). Often, too, these details were more successful than the faces because they were less dependent on his relationship (or lack thereof) with the subject and more the result of his ever-increasing ability to extract meaning and significance from the smallest elements of life (Key Set numbers 604, 607, 715, 716, and 719–721).

A lighthearted, playful quality, coupled with a more daring experimentation, entered Stieglitz’s work in the early 1920s. Although he and Emmy did not divorce until 1924, O’Keeffe’s arrival in New York in 1918 marked the end of that deeply unhappy marriage. Freed from his responsibilities as a gallery owner and publisher, invigorated by his love for O’Keeffe and his renewed creativity, Stieglitz was also inspired by the support he garnered from the new community of artists and critics that gathered around him. While many of the American artists he had first met at 291, including Demuth, Dove, Hartley, Marin, and Strand, continued to seek his guidance, so too did a new, younger generation of critics, writers, and poets, including Waldo Frank, Paul Rosenfeld, Sherwood Anderson, Jean Toomer, Hart Crane, and William Carlos Williams (Key Set numbers 642–644, 846–851, 1072–1074, and 1077–1091). Their youthful and passionately espoused belief that, following the horrific destruction of World War I, America could “no longer be of Europe,” propelled Stieglitz to articulate a new course for his work. Like them, he came to believe that American artists must “identify with one’s native ground” and “try to attune oneself to a place.” Understanding their mission as the creation of an America “without that damned French flavor,” as Stieglitz wrote, Frank, Anderson, Rosenfeld, and others urged the creation of an intuitive, non-theoretical art, based on direct observation and experience. “We make our own not what we think,” Frank and James Oppenheim explained, “but what we feel.”

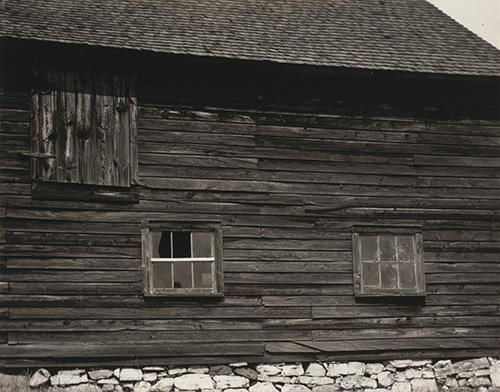

In the late 1910s and early 1920s, encouraged by the critical writing of the period and by the work of Dove, Marin, and especially O’Keeffe, Stieglitz, for the first time in his art, began to explore the rural American landscape. Photographing the hills, trees, and barns at Lake George, he studied the relationship between natural and man-made forms. He contrasted the strong geometry of the white, horizontally patterned clapboard siding on the Lake George barn with the dark, gnarled, and thrusting branches of a tree in the foreground, and he humanized the natural world by extracting the sinuous, limblike forms in The Dancing Trees (figs. 9 and 10; Key Set numbers 701–702).

As Charles Sheeler had done in 1917, he also found the abstract in vernacular American architecture (figs. 11 and 12). Like the other artists he came to call the Seven Americans—Demuth, Dove, Hartley, Marin, O’Keeffe, Strand, and himself—he investigated a variety of new subjects and materials in the early 1920s. Understanding photography as an essential part of a new anarchism, a revolt against an outmoded aesthetic order that resonated with his rebellious spirit, he espoused dada’s anti-art agenda. He wrote in 1921, for example, that “ART, SCIENCE, BEAUTY, RELIGION, every ISM, ABSTRACTION, FORM, PLASTICITY, OBJECTIVITY, SUBJECTIVITY” were “fast-becoming obsolete terms,” and in works such as The Way Art Moves, 1920, Spiritual America, 1923, or a symbolic portrait of himself and O’Keeffe’s sister Ida as an apple with a crow’s feather stuck into it, he adopted dada’s scatological wit and punning titles (Key Set numbers 623, 889, and 1039). Like the dada artist Man Ray, Stieglitz explored the mysterious, uncontrollable qualities that could be achieved by allowing his palladium prints to solarize. And, if we believe, as he claimed, that his 1919 double exposure of Dorothy True’s leg superimposed over her face was unplanned, he also employed the dada idea of elevating the accidental to a work of art (Key Set numbers 604–607). He further proclaimed his anti-art agenda also when he placed True’s foot on pieces of mat board—that is, had her step on his art.

Perhaps as a result of this more active and animated life, perhaps in response to the dada artists’ exploration of alternative sources for art in the stuff of life, and the interest in folk and ethnic art that pervaded the work and ideas of so many artists associated with him, Stieglitz more vigorously investigated the most amateurish aspect of photography, the snapshot. Like the children’s art that he had exhibited so frequently at 291, snapshots were quickly, even carelessly and thoughtlessly made, with no concern for whether the results were “art or not art.” Because of what Hartley described as their “simple registration of and adherence to facts for themselves” and “unmistakable authenticity of experience,” snapshots gave Stieglitz a liberating alternative to the sterility and seriousness of much traditional art and a vision that was unique to photography. Like many other photographers of the time, ones known and unknown to Stieglitz—from Man Ray to László Moholy-Nagy to André Kertész—he had made snapshots for many years, primarily of his family, but he thought them too much of a “gamble” and saved few for his collection.

In 1922, though, a confluence of events propelled him to examine the potential of this approach more seriously and caused a significant change in his art. That August, he received a draft of a paper by Frank in which he asserted that the power of Stieglitz’s portraits lay in his ability to “mold,” or, as Stieglitz interpreted the comment, “hypnotize” his subjects. Determined to prove that he had no such special power over his subjects, he sought something to photograph that he had little ability to control. Using his 4 × 5-inch hand-held camera, he initially made evocative but studied depictions of the apples by the Lake George house, including After the Rain and Gable and Apples (Key Set numbers 776 and 777). His style loosened considerably, though, when Strand’s new wife, the uninhibited Rebecca (Beck) Salsbury Strand, came for a visit in September 1922 (Key Set numbers 750–767). In a series of rapid, almost cinematic snapshots of Beck as she swam and toweled dry, Stieglitz realized that he did not need to compose his photographs carefully, either in the camera beforehand or the darkroom afterwards. But, by making “an image of what I have seen, not of what it means to me” he could create a more immediate, intuitive, and almost subconscious response to the life around him. Just as the less verbal, more intuitive O’Keeffe was able, as he wrote, to put her “experiences into paint,” so too could he, in these casual, unstudied “eye-openers” more easily put “his feelings into form.” This was an art that spoke directly of the moment of exposure and of his relationships with the people and things around him. “I do not ‘think’” any longer, he wrote to Anderson in 1923, “I just feel.”

At the same time, Stieglitz also investigated a different kind of photographic printing paper. In part because of the growing cost of palladium paper and his declining income, and in part, too, because of comments by the critic Henry McBride and Sheeler that his photographs, “printed luxuriously upon the rarest of papers,” were “essentially aristocratic and expensive,” Stieglitz began to consistently use gelatin silver paper. In keeping with his exploration of the common snapshot, he also went a step further and used postal card paper, the cheapest, most readily available photographic paper.

Stieglitz presented all of these innovations in his 1923 exhibition at the Anderson Galleries. Including 115 prints never before exhibited and made, primarily, in the last three years, he showed more than eighty-five portraits, as well as landscapes and snapshots. In addition, though, he exhibited ten 8 × 10-inch photographs of clouds floating above the Lake George skyline that were made in 1922 in response to Frank’s supposed charge: surely, he reasoned, no one could accuse him of “molding” or “hypnotizing” something that moved so freely, swiftly, and distantly across the sky (Key Set numbers 792–802). Following the Seven American artists’ Whistlerian penchant to relate their work to music, he titled them Music: A Sequence of Ten Cloud Photographs, or alternately Clouds in Ten Movements. And their sequence is musical: as in a symphony, a clear beginning, middle, and end are marked by a sense of progression through an emotional experience.

Figure 13

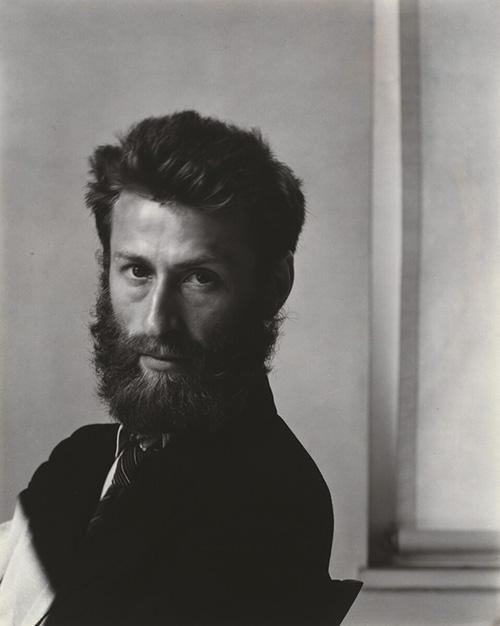

Paul Strand, Alfred Stieglitz, Lake George, New York, c. 1920, printed early to mid-1980s, gelatin silver print, Philadelphia Museum of Art: The Paul Strand Collection, partial and promised gift of Marguerite and Gerry Lenfest, 2009-160-587. © Aperture Foundation, Inc., Paul Strand Archive

Inspired by the imagery of the clouds and by the insights he had gained working with the hand camera, in the summer of 1923 Stieglitz became consumed with photographing clouds: of the sixty-one photographs in his 1924 show at the Anderson Galleries, forty-seven were photographs of clouds, all made with his small camera. The bulk and weight of his 8 × 10-inch camera made it difficult for him to photograph much above the horizon line, but he could point the smaller hand-held camera in any direction, at the zenith or the horizon (fig. 13). He instantly explored its possibilities: less than a dozen of the more than 150 photographs of clouds he made in the summer of 1923 include any reference to the ground. The Songs of the Sky, as he now called them, were, as O’Keeffe wrote, “way off the earth.” With no horizon line to anchor the picture or the viewer, they have no “up” or “down,” creating a strange sensation of disorientation and abstraction. With no objects depicted other than clouds, they have no sense of scale, establishing an odd tension between the vastness of their nominal subject—the sky—and the smallness of the photograph itself. Often, Stieglitz made two prints from the same negative and mounted them in different orientations; occasionally he indicated that a photograph could be hung in any orientation, that “all ways were up” (see, for example, Key Set numbers 1210, 1215, and 1225). By draining these subjects of their familiar identity and arrangement, he liberated the forms from what they were in nature and gave them a more pure, expressive life.

His photographs of clouds vary markedly from year to year. Several from 1923 are abstract portraits, both of O’Keeffe and Rhoades; others consist of bold, “big” forms, often with dramatic lighting and dense, all-over patterning (Key Set numbers 876–988). Those from 1924 frequently include the line of the hill while those from 1925 and 1926 have both light, wispy clouds and darker, more densely patterned ones (Key Set numbers 1054–1069, 1093–1137, and 1159–1178). 1927 was a year of exuberant experimentation with big cumulus clouds, even trees, often comically resting on their sides (Key Set numbers 1198–1239). Creating a dizzying sense of disorientation, in 1925 and again in 1927 he also mounted some photographs so that the line of a hill or the top of a tree appears in one of the top corners of the print; in 1927 he sometimes placed trees in the corners of prints so that they appear to be growing diagonally (see Key Set numbers 1203 and 1225). In 1928 he made only one photograph of clouds, no doubt because he was weak after a severe angina attack, while in 1929 he made more than fifty dark and brooding ones, most of which were taken while O’Keeffe was away in New Mexico (Key Set numbers 1253–1302).

In 1923 and 1929, perhaps in anticipation of exhibitions, Stieglitz also grouped his photographs of clouds into series. Most of the series from 1923 appear to have been put together after they were taken and contain clouds that differ widely; often the series are united by photographs placed at the beginning and end that have cloud patterns that echo one another (see, for example, Key Set numbers 882–886). Often, too, the 1923 series are musical or narrative in their linear progression: usually one or two photographs state a theme, followed by variations, and a recapitulation (Key Set numbers 905–914). The series from 1929 are significantly different. Instead of constructing a sequential flow of images, Stieglitz joined together several photographs, usually of similar tones and patterns, into nonlinear groups with no clear beginning, middle, or end (figs. 14–18).

Figures 14, 15, 16, 17, 18

Alfred Stieglitz, Equivalents, Set C2 Nos. 1–5, 1929, gelatin silver prints, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.1033–1037

Key Set numbers 1253–1257

While many of the groups contain photographs made at the same time, they do not document a literal progression of time in a cinematic fashion; instead Stieglitz reshuffled the photographs to suit his pictorial needs. Like a deck of cards that could be dealt in any number of ways, he also did not conceive of a series as a stable or discrete entity, but moved duplicate prints from a negative to different positions in other series (see, for example, Key Set numbers 1264 and 1265).

In March 1925, when Stieglitz showed his cloud photographs in the Seven Americans exhibition at the Anderson Galleries in New York, he abandoned the more poetic title Songs of the Sky for the terser but richer term Equivalent. As he explained, “I have a vision of life and I try to find equivalents for it sometimes in the form of photographs”; later, more portentously, he said that the cloud photographs were “equivalents of my most profound life experience.” Drawing on the symbolist notion of synesthesia—the possibility of suggesting one thing by means of another—many of the 291 artists had used the term equivalent to denote, as Hartley said, “a sign or symbol for the ideas of the spirit.” “I do not avoid objectivity nor seek subjectivity,” Walkowitz wrote in 1916, “but try to find an equivalent for whatever is the effect of my relation to a thing.” Merging this with their desire to create an art that addressed a more spiritual America, the artists and writers associated with Stieglitz in the 1920s frequently spoke of their attempts to construct “a graphic equivalent” of their “experience of life” and of extracting “an aesthetic equivalent of the land.” Working “from the unconscious to the conscious, from within out,” they wanted to discover, as Strand wrote, “psychic equivalents, deeply related to those of music” and clarify experience to make, as O’Keeffe explained, “the unknown—known.” By abstracting clouds from their relationship to the ground and thereby freeing them from a specific time and place, Stieglitz wanted viewers to become “less aware of clouds as clouds.” Just as Williams sought to “disassociate” words “from natural objects and specified meanings” and liberate them “by transposition into . . . the imagination,” so too did Stieglitz strive to create a new language for photography that was less dependent on subject matter, more experiential and intuitive, and more expressive of mood or an emotional state. “In looking at my photographs of clouds,” Stieglitz concluded, “people seemed freer to think about the relationships in the pictures than about subject-matter for its own sake.” Like Dove, he wanted to create something that had its own reality and did “not lean on other things for meanings.” By grouping them into series so that they became something that was experienced in and through time, and especially with the later series, and by arranging them so that where there is no beginning, middle, and end, the clouds became a metaphor for the motions of the spirit and the fluidity of life itself. “Life,” as Stieglitz told Beck Strand, “is like a Chinese play—It just goes on—no beginning—no end—no plot.” In Stieglitz’s series, as in Bergson’s notion of continuous change or Gertrude Stein’s continuous present, the present flows into the past as the future flows into the present, creating an almost imperceptible but undeniable sense of change.

In December 1929, just weeks after the stock market collapsed, Stieglitz moved into his last gallery, An American Place, dedicated to the art of the “Seven Americans.” Located on the seventeenth story of an office building at Madison Avenue and 53rd Street, the windows of An American Place overlooked the city to the north and west. The clean, elegant design of the gallery was perfectly in keeping with the aesthetic of the art exhibited, but increasingly An American Place came to be seen as isolated from the life on the street below. Stieglitz’s devoted followers continued to visit, as did some younger artists, curators, and writers, such as Ansel Adams, Eliot Porter, and Beaumont and Nancy Newhall. As the Depression grew worse, though, and as numerous other American painters and photographers, including Thomas Hart Benton, Ben Shahn, Walker Evans, and Dorothea Lange were increasingly attentive to the American scene, using their work to effect social and political change, Stieglitz’s art was perceived as precious, elitist, and out-of-step with the tenor of the time. And his conviction that art could remake society, by replacing materialistic values with more spiritual ones, seemed increasingly anachronistic and naive. By the early 1930s he was excoriated by artists and writers on the left for not taking a stand in support of the needs of the poor and by conservative critics on the right who wanted to undermine his efforts on behalf of modern American art. As his public persona suffered in the 1930s, so too did his personal life: he had an affair with the much younger Dorothy Norman; O’Keeffe, perhaps as a result, began to operate more independently, making her own decisions about which commissions to accept; and his poor health was exacerbated when O’Keeffe suffered a breakdown in late 1932 and was hospitalized in 1933. As a result, he entered a period of intense self-examination and his art changed markedly.

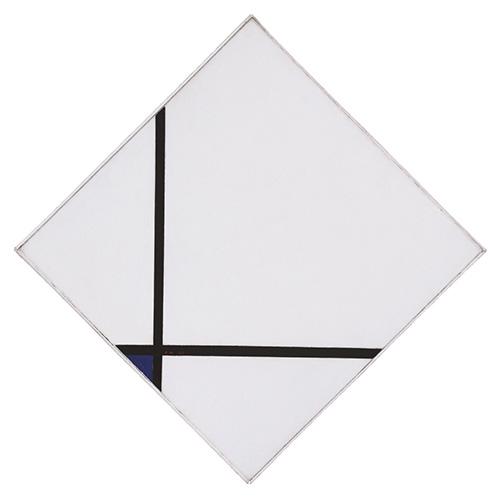

In the spring of 1930 he discovered—or more accurately rediscovered—the theme that would reinvigorate his work for the next few years: the changing face of New York. Possibly inspired by O’Keeffe’s 1927 paintings of New York and certainly influenced by Piet Mondrian’s “diamond” paintings shown at the Société Anonyme exhibition of modern art at the Brooklyn Museum from November 1926 to January 1927, Stieglitz had made a few 4 × 5-inch photographs of New York in the spring of 1927 (figs. 19 and 20). From the window of the Intimate Gallery, he took several studies of the Sherry-Netherland Hotel under construction in the background. With Mondrian’s painting in mind, Stieglitz photographed the horizontal and vertical lines of the skyscrapers with their dominant black and white tones, and even rotated his camera to create his own “diamond” photograph. With the exception of this work, however, most of his 1927 studies of New York are tentative; they neither accurately convey the scale and vigor of the city nor contain his conflicted views about it (Key Set numbers 1181–1185 and 1187–1190).

Still working with his 4 × 5-inch hand-held camera, his series of three photographs taken from the windows of An American Place—the first made most likely in March 1930 and the second two in late May or June—record the construction of the Hotel Pierre and two smaller buildings with a boldness absent from his previous works (Key Set numbers 1320–1322). When he returned to New York from Lake George in the fall of 1930, the idea of recording the changing image of New York continued to intrigue him, as it would for the next two years. Working mainly with his 8 × 10-inch camera, whose greater size and clarity of focus better captured the visual complexity of the scenes before him, he photographed the construction of the Hotel and Industrial Mart, as it was seen from his windows at An American Place, directly across the street, and from his rooms on the thirtieth floor of the Shelton Hotel where he and O’Keeffe lived (Key Set numbers 1357–1359 and 1374–1392). From the Shelton Hotel, he also photographed the construction of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, the R.C.A. Victor Building, and 444 Madison Avenue (Key Set numbers 1350–1356).

The resulting photographs, almost thirty-five in a year, have a formal strength and lucidity that is unknown in his previous work. Unlike many artists in the 1920s—O’Keeffe, Marin, Joseph Stella, Louis Lozowick, or Hugh Ferris, for example—Stieglitz did not emphasize the soaring skyscrapers or the vertiginous views from them, nor did he, like Evans or Berenice Abbott in their photographs of the city in the early 1930s, explore the life on the streets below. His physical point of view was most similar to that of Lewis Hine—both depicted the city as it was seen from high up in the skyscrapers themselves—but his intention and tone were diametrically opposite. Whereas Hine in his 1932 book Men at Work: Photographic Studies of Modern Men and Machines celebrated the skill and daring of the workers who constructed the new skyscrapers, Stieglitz, as he had done throughout his life, eschewed any purpose other than his own creative expression and used the external to mirror his internal state of mind: as he wrote at the time, “I do it solely to satisfy something in me.” From his perch at An American Place or the Shelton Hotel, he photographed the skyscrapers straight on, projecting himself as almost their equal; this was, as he stated unapologetically, the view From My Window at An American Place, North or From My Window at the Shelton, West (Key Set numbers 1357–1359, 1374–1381, and 1389–1391). Often dense with detail, Stieglitz’s photographs hover, like the city—and his personal life—on the verge of chaos. Yet, through careful framing, choice of the time of day, attention to the ever-changing shadows of the buildings, and his pristine, highly waxed gelatin silver prints, he was able to extract a coherent meaning from the world outside his windows. At their core, Stieglitz’s photographs, like Hine’s, are fundamentally about power. Hine’s speak to the individual and collective power of the workers who were profoundly altering the landscape of their city; Stieglitz’s reveal the power of the artist to confront, order, and even control the external world.

Stieglitz showed these photographs in his exhibition at An American Place in 1932. As he had done with almost all of his one-person shows, especially those in the 1920s and 1930s, he rooted his newest photographs in his older studies, demonstrating similarities not just in subject matter and style, but approach and meaning. In 1924, for example, when he first exhibited his small compositions of rapidly changing clouds, he also showed small gelatin silver contact prints of The Terminal and The Steerage that were equally complex and fluid. He surely recognized that both early and later prints utilized a dense, overall patterning in which composition, in traditional terms, no longer applied (Key Set numbers 95, 96, and 314). His 1932 exhibition included both old and new photographs of the city and revealed his newly perceived understanding of its evolution from the polyglot community seen in Five Points, New York (Key Set number 81) or Coenties Slip (Key Set number 80)—made most likely in 1893 and exhibited for the first time in 1932—to a hopeful emblem of the twentieth century, embodied in Lower Manhattan, 1910 (Key Set number 339), to a beautiful but cold and inhuman spectacle, seen in his last photographs from the 1930s. No longer interested in capturing the “myriad moods” of the city, he retitled many of his earlier works with less effusive, more factual descriptions: The Street—Design for a Poster became Fifth Avenue—30th Street, while Spring Showers—The Street Cleaner became Street Sweeper and Little Tree (Key Set numbers 268, 271, and 272). He also presented such earlier views as Sunday Afternoon—From My Window, 1111 Madison Avenue, Looking South—exhibited for the first time—to demonstrate his prior penchant to observe and document the changing view outside his window (Key Set number 276).

As he had done in his previous exhibitions of his photographs of O’Keeffe and clouds, he further intensified this sense of change by grouping his studies of New York into series, showing, for example, nine views From My Window at An American Place, North and ten views From My Window at the Shelton, West (see, for example, Key Set numbers 1321, 1350–1355, 1357, 1358, 1379, 1381, 1383, 1384, 1386, 1388, and 1391). Yet, unlike his portrait of O’Keeffe, which consisted of multiple moments intended to create a larger synthetic whole, and unlike the Equivalents in which abstract constructions evoke a continuous present, Stieglitz’s New York series were almost cinematic, charting both the growth of the skyscrapers and the more subtle but constantly changing patterns of light and shade formed by the shadows of the buildings. By recording their relentless growth, Stieglitz’s photographs pointed to the irony that these buildings, planned during the exuberance of the late 1920s, were built during the painful years of the Depression. It was foremost in his mind. More than one visitor to An American Place recalled hearing Stieglitz rail “at the empty, overornamented skyscraper across the street, built while artists starve; at the building of Rockefeller Center while the Detroit Art Museum has been closed and that in Philadelphia is threatened with closure.” Only one photograph in all of his many views made at this time shows a person, and he, as a critic observed, works “in a crowded and sordid” city, “built of pasteboard,” and in an office building with “plaster cornices [that] look far more flimsy and meretricious than a house built of cards ever could” (Key Set number 1446). These photographs, though, speak not only of the duality Stieglitz perceived in the world around him—its beauty and waste, awe and horror, vitality and emptiness—but also of the inevitability of change itself. Once the buildings were completed, the taped “X”s on the windows removed, and lights turned on, illuminating their interiors at night and indicating life within, Stieglitz generally lost interest in photographing them for that sense of change and conflict, the tension between old and new, the ephemeral and the eternal, was no longer present.

Once again, the act of mounting an exhibition caused him to look at another aspect of his work. After his 1932 show closed he made three more photographs out of the windows of An American Place, then abandoned the subject until 1935. Instead, he increasingly turned his attention to portraits and other studies made at Lake George. From the mid to late 1920s Stieglitz had occasionally made snapshots of O’Keeffe but these were far less engaged than his earlier studies of her had been and no different from other casual records he made of family and friends at Lake George. In the early 1930s, though, at the time their relationship was most severely tested, she reappeared as a major subject in his art. The distance between them, especially in the early 1930s, is obvious (Key Set numbers 1524–1526, and 1529). While there are moments of warmth and affection, often she looks—almost stares—directly at him, and frequently, passive and resigned, she gazes off to the side. He photographed her nude for the first time in nine years, but the coolness, abstraction and reserve to these photographs is not only the result of the colder, crisper gelatin silver paper (Key Set numbers 1438–1444). He depicted her with objects from her life in New Mexico—bones and blankets—and while in a sense he was sharing her subjects, he was also pre-empting them, for he photographed them even before she had a chance to paint them (Key Set numbers 1427–1429). Frequently, he placed these emblems of her independence—not only the bones and blankets, but also her car and even her studio—between them, so that she was wrapped in her blanket, behind her car door, looking out of the window of her studio, not next to him as she had been in the late 1910s and early 1920s (Key Set numbers 1430–1437, and 1490–1493). With their metallic sheen, deep blacks, and complex geometry, Stieglitz’s photographs of O’Keeffe from this period, especially those of her leaning on the spare wheel of her car, wearing her New Mexican blanket and bracelet, are among his strongest but also most poignant works (Key Set numbers 1515–1519). Frankly acknowledging the chill that existed between them, these deeply personal photographs must also have been some of the most difficult works for him to make. O’Keeffe, as well, was acutely aware that he was also photographing the ever-present and far more worshipful and willing Dorothy Norman at this same time (Key Set numbers 1393–1402).

As Stieglitz spent more time alone at Lake George in the 1930s, the farmhouse and its surrounding fields, trees, sheds, and his darkroom, as well as the lake below, became the focus of his art. Like his photographs of New York from the same time, these are rigorous but also quiet and intensely autobiographical works. Just as he had studied the changing views from his windows at An American Place or the Shelton Hotel, so too in the summer of 1932 did he record the shifting shadow of the house on the grass going down to the lake, indicating both the presence of his family and its constantly changing relationship to that place (Key Set numbers 1471 and 1472). With the same precise attention to framing and detail seen in his photographs of New York, he recorded the section of the porch on the Lake George house where O’Keeffe had the roof removed to allow more light into Stieglitz’s adjacent study (Key Set number 1543). By contrasting the ordered structure of the house with the lushness of the grapevine growing up and over the railing, he created an eloquent and telling statement of his and O’Keeffe’s life at Lake George. And just as he directly tackled the majestic but ominous skeletons of the new order that were being constructed in New York, so too did he confront the slow disintegration of his life at Lake George in a series of studies of the dying poplar trees (Key Set numbers 1467–1470, 1474–1475, 1500–1502, 1550–1552, 1575–1577, and 1595–1601). Stubbornly clinging to life and retaining their silvery, desiccated beauty, the poplars were, as he admitted, emblems of himself. Literally and metaphorically focused, intense, and brilliant, these photographs made at Lake George in the early 1930s reverberate with a sense of time and change, with memories of the past, with an awareness of the family and the relationships that had once given meaning to the landscape, and of their current absence.

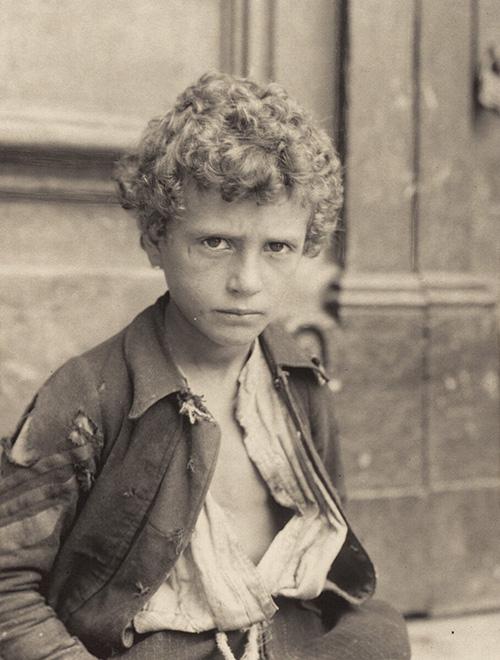

Stieglitz presented many of these photographs in his last one-person show at An American Place late in 1934. Following closely after the publication of America & Alfred Stieglitz, a book of essays celebrating his life and art, his 1934 show was intended to position him in history and counter his critics: eleven of the twenty-three earlier works were—like so many paintings and photographs by other artists from the 1930s—portraits of anonymous people performing menial tasks. Including only works made the first and last decades of his career, the exhibition also illustrated the connections he now saw, between, for example, his 1894 study of a Black Forest House and his 1934 House, Leaves and Tree; his 1894 Harvesting, Black Forest and his 1933 Grasses; his 1894 Venetian Gamin and his 1933 portrait of Ernest Gutman (Key Set numbers 177 and 1540, 196 and 1504, and figs. 21 and 22). Again, Stieglitz exhibited all the earlier works as gelatin silver prints, exchanging their late nineteenth-century tone, sentiment, and atmosphere for clarity, fact, and potency.

During the 1930s and early 1940s, as he selected work for exhibitions and strove to create order, he also systematically appraised his collection, reviewing and eliminating, reprinting and even remounting work from throughout his life. (At the same time, he purged his collection of work by other early twentieth-century photographers—things that looked decidedly “queer” to him—donating more than 350 pictorial images to The Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1933.) While he destroyed many early prints he also examined the numerous snapshots he had made in the last two decades of family and friends, excising dozens of prints and striving to retain, on the whole, only those that were most fully resolved and expressed something deeper: “the essence of childhood,” as Dove described Stieglitz’s study of his greatniece, Peggy Davidson, or “the faithful, devoted” housekeeper, Margaret Prosser (Key Set numbers 1041, 1604, and 1605). No doubt to spare O’Keeffe, numerous photographs of Norman were also removed and given to Norman herself. Yet he treated his 8 × 10 inch photographs in a significantly different way. While he undoubtedly chose not to print many large photographs made after 1915, he preserved almost all that he did. The Key Set is known to be missing only one of the views Stieglitz made of New York in 1915 and 1916; only six large portraits of O’Keeffe; and only six studies of New York from the 1930s. And of the smaller photographs of clouds, which he considered his most important work of the 1920s, only nine are not represented in the Key Set.

In the years immediately before and after Stieglitz stopped photographing in 1937 he frequently spoke of ever-grander projects that he knew he would never realize. He told Charlie Chaplin of his hope to make a “movie of a woman’s eyes, their changing expression, the hands, feet, lips, breasts, mons veneris, all parts of a woman’s body, showing the development of a life, each episode alternated with motion pictures of cloud forms on the same theme.” He told Evelyn Scott that if he had been a rich man, he would have owned racehorses and made a series of photographs telling the story not only of “The Sky,” “Woman,” and “the Earth,” which he had partially explored, but also “the Life of a Racehorse.” He wanted to construct massive groups of photographs that would reveal all facets of the evolution of an individual’s life: his physical, intellectual, and emotional growth; his ever-changing relationships with other people; and his increasingly more complex understanding of the world around him. To a great extent, that larger whole that Stieglitz sought to create—that life revealed in and through photography—can be found in the Key Set.

Originally published 2002; minor adaptations have been made for the presentation of this text online.