Stories

Read, watch, or listen to inspiring stories about art and creativity.

Jump to:

Editor’s picks

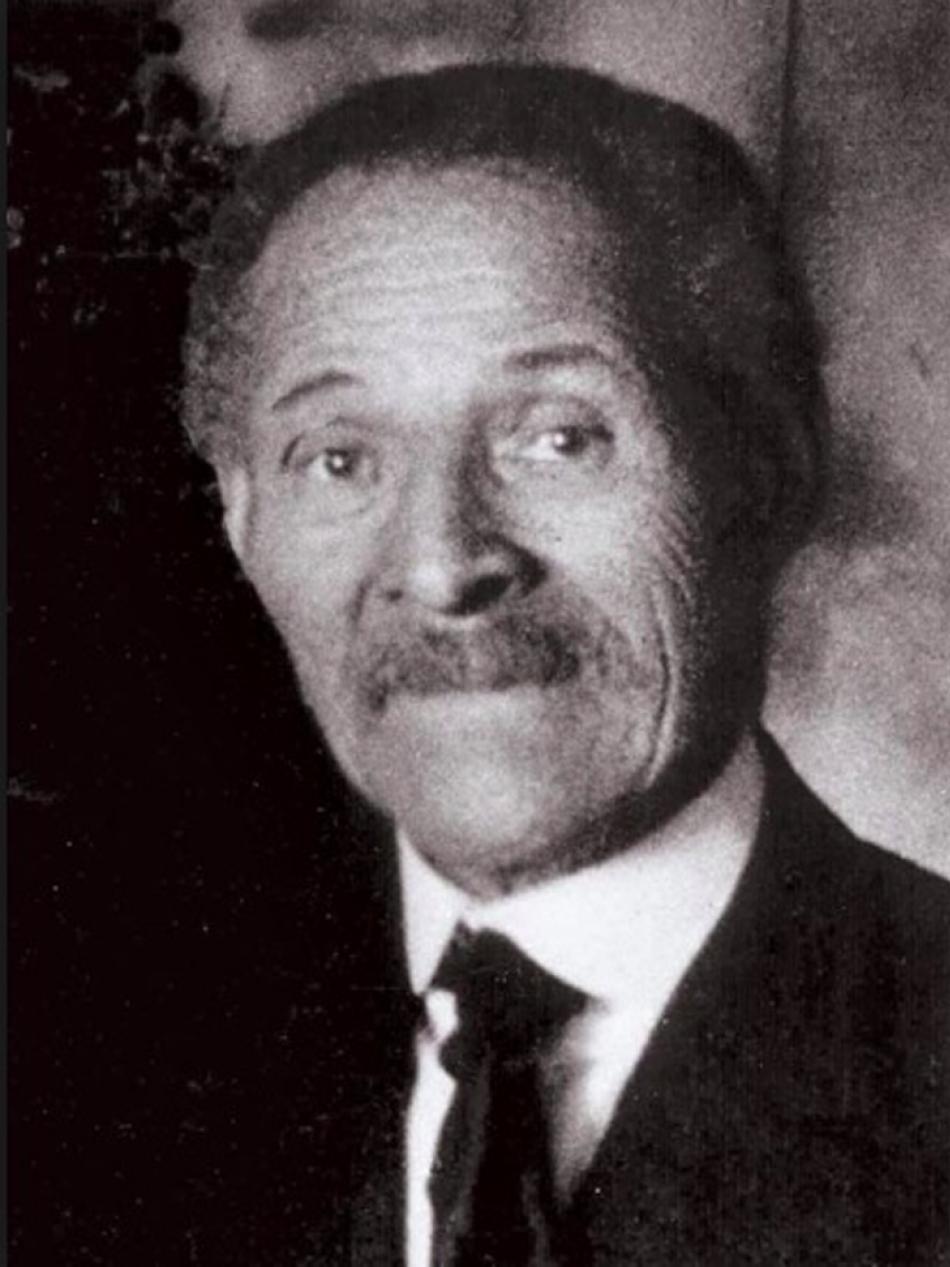

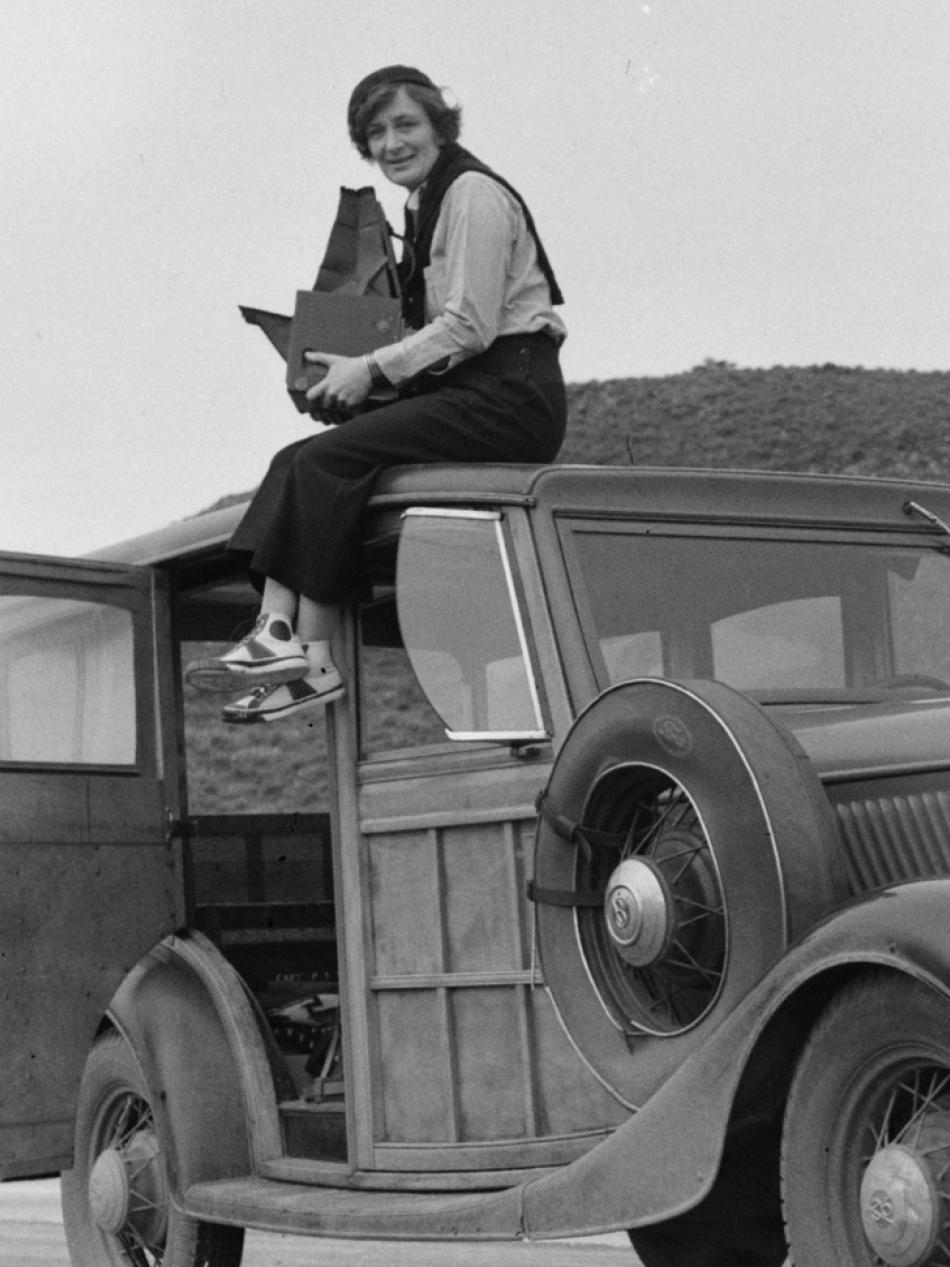

Charles White, Elizabeth Catlett in Her Studio, 1942, Courtesy of The Charles White Archives.

Article: Who Is Elizabeth Catlett? 12 Things to Know

Meet a groundbreaking artist who made sculptures and prints for her people.

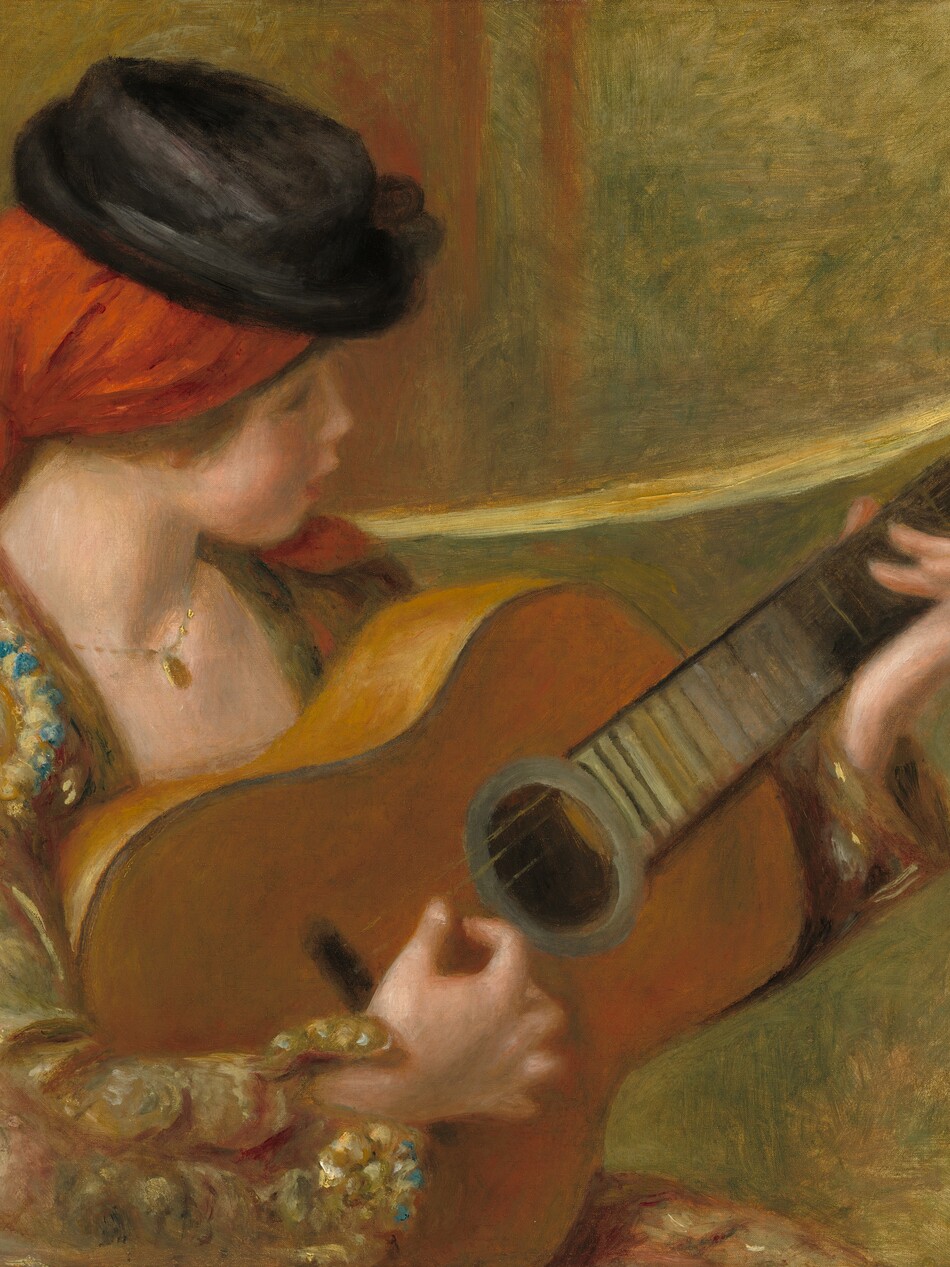

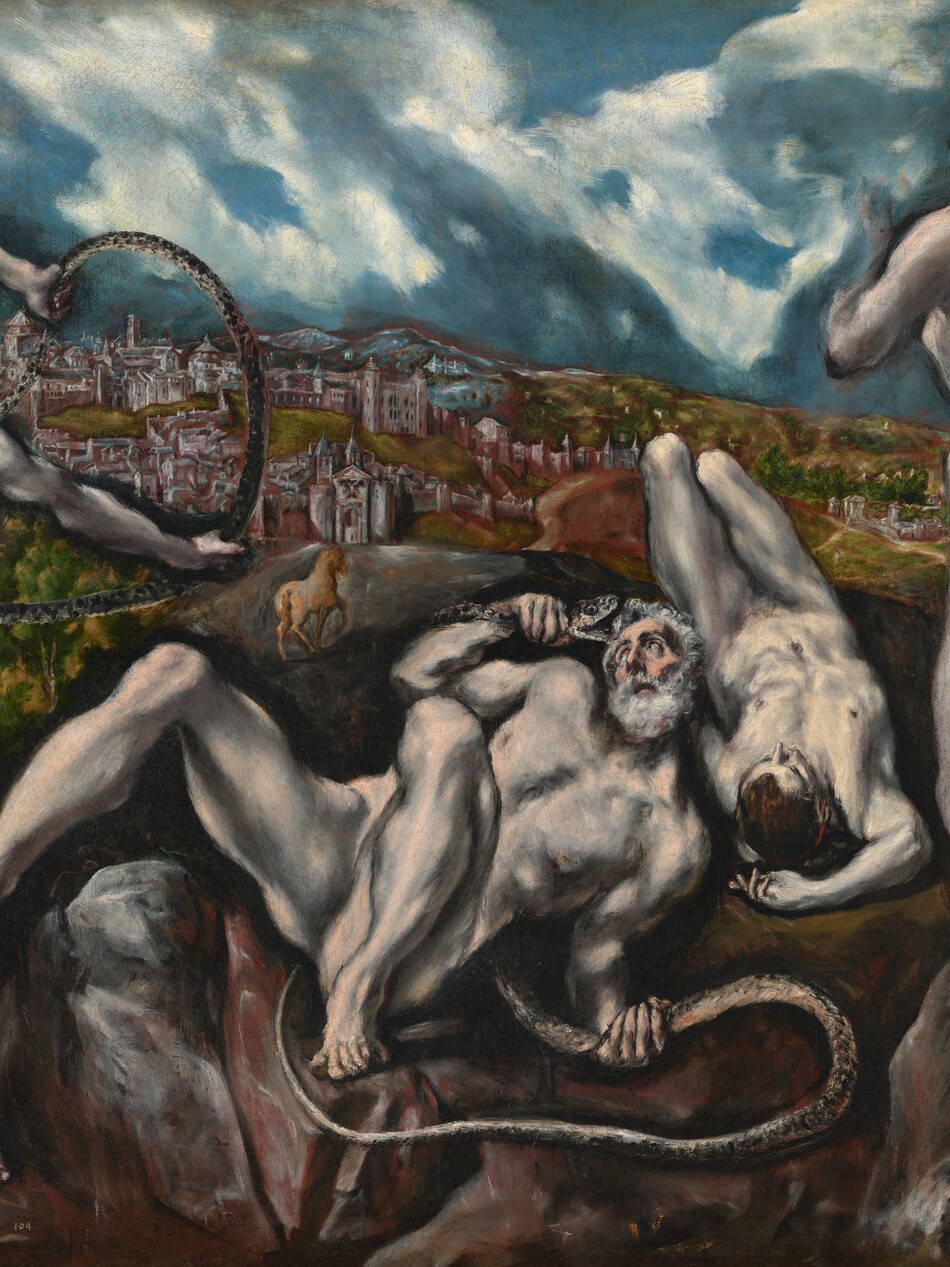

Video: Look Closer: The Art of Devotion

Explore powerful stories of devotion, love, and artistic passion through iconic works of art—from religious masterpieces to revolutionary portraits.

Interactive Article: The Marvelous Details of Joris Hoefnagel’s Animal and Insect Studies

Scroll to discover tiny brushstrokes, hidden meanings, and the immense impact on our understanding of the natural world.

Articles

Look closer

Interactive Article: How the Index of American Design Kickstarted Edward Loper’s Art Career

The acclaimed Delaware artist first brought his artistic ambitions to life drawing decorative art objects for the Work Progress Administration project.

Interactive Article: The Marvelous Details of Joris Hoefnagel’s Animal and Insect Studies

Scroll to discover tiny brushstrokes, hidden meanings, and the immense impact on our understanding of the natural world.

Article: Seven Highlights from the Index of American Design

Peer into the American past with a collection of Great Depression–era watercolors.

Article: Who Is Elizabeth Catlett? 12 Things to Know

Meet a groundbreaking artist who made sculptures and prints for her people.

Article: From Old Car Tires, Chakaia Booker Reveals Beauty and Devastation

Transforming discarded tires into monumental sculptures, the artist reflects on the environmental impact of our daily commutes.

Interactive Article: Layers of Power in "The Feast of the Gods"

At first glance, this painting looks like a great party. But it’s more complicated than that.

Videos

Catch up on our latest videos

Video: Look Closer: The Art of Devotion

Explore powerful stories of devotion, love, and artistic passion through iconic works of art—from religious masterpieces to revolutionary portraits.

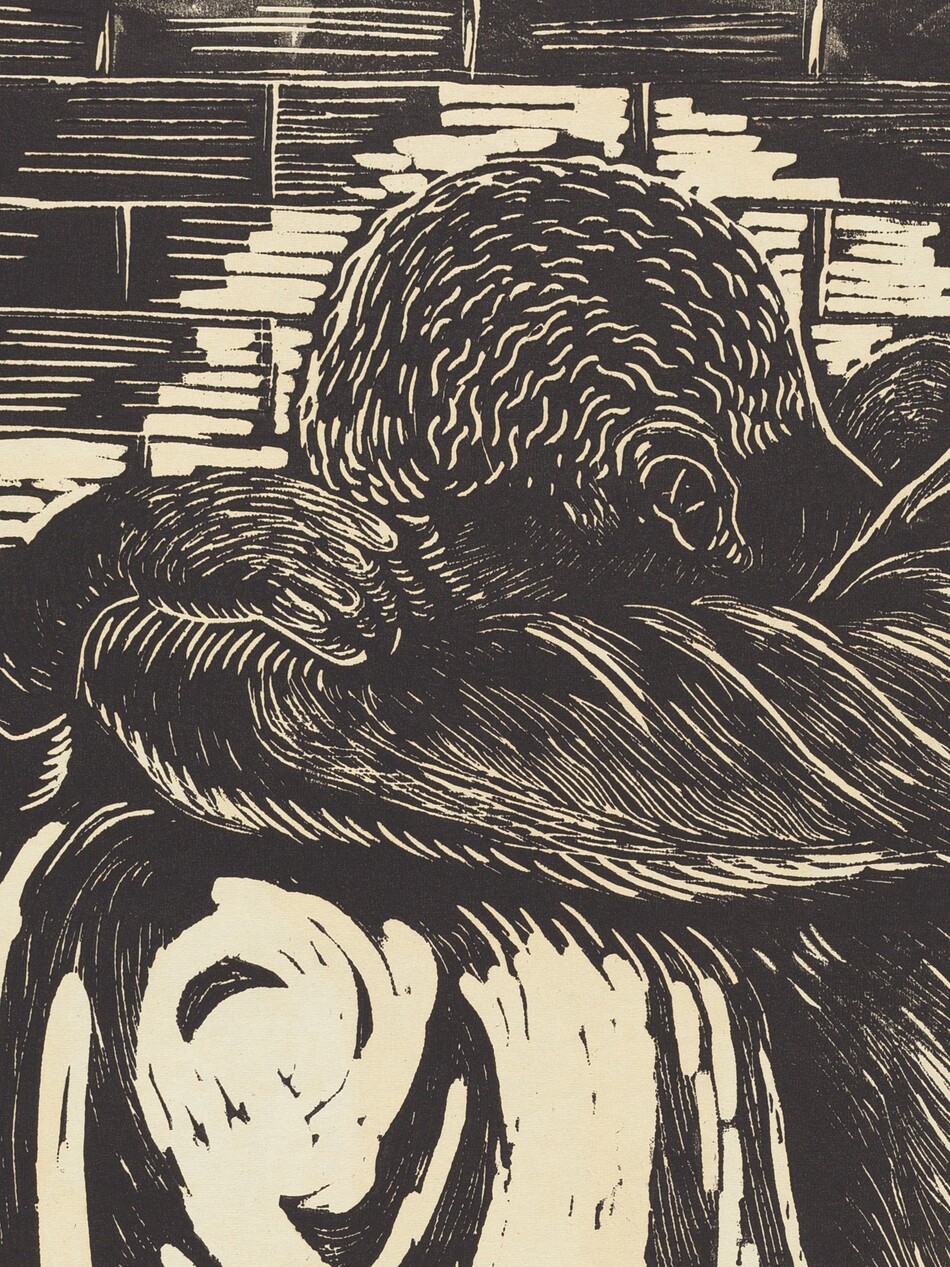

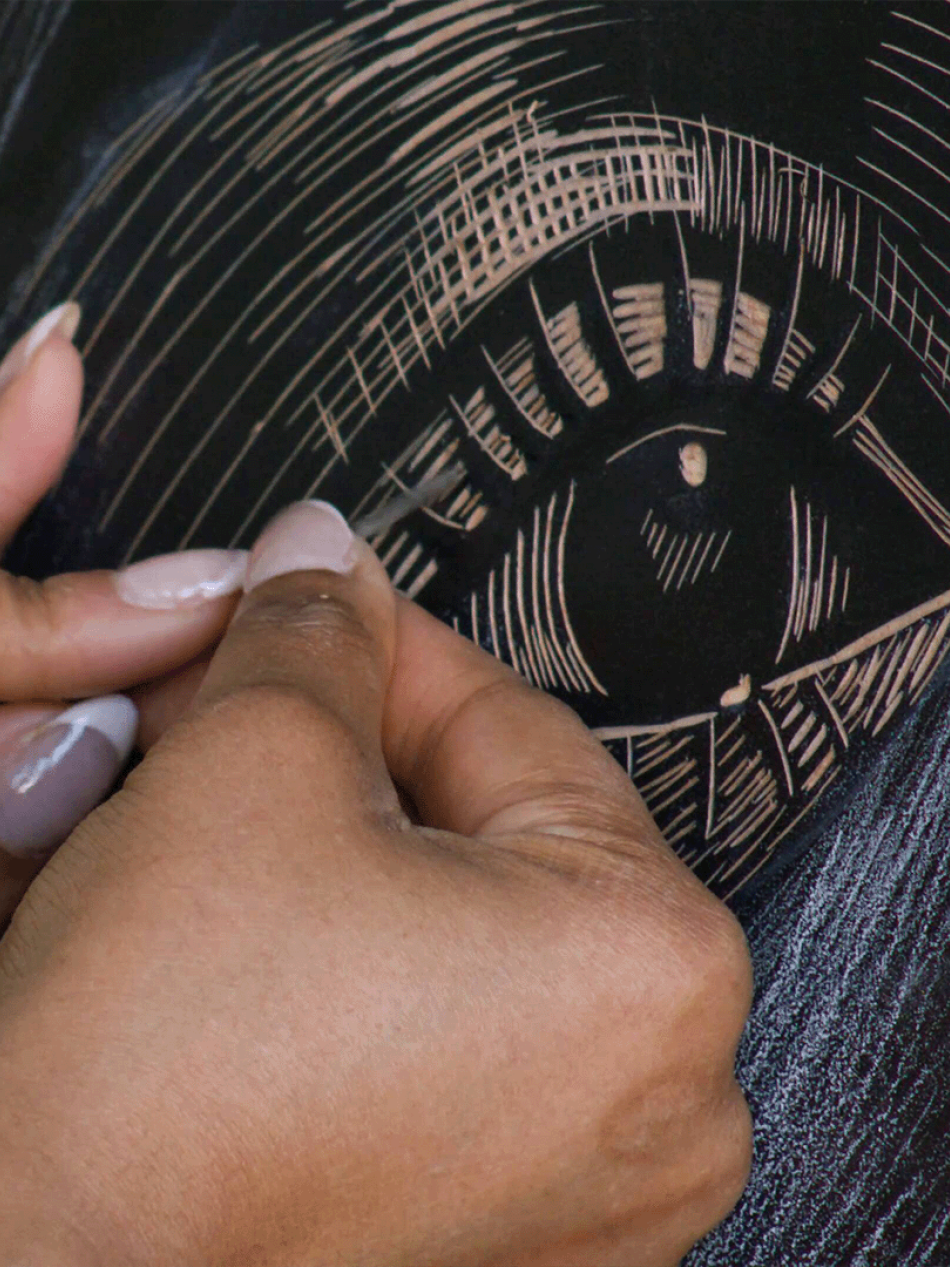

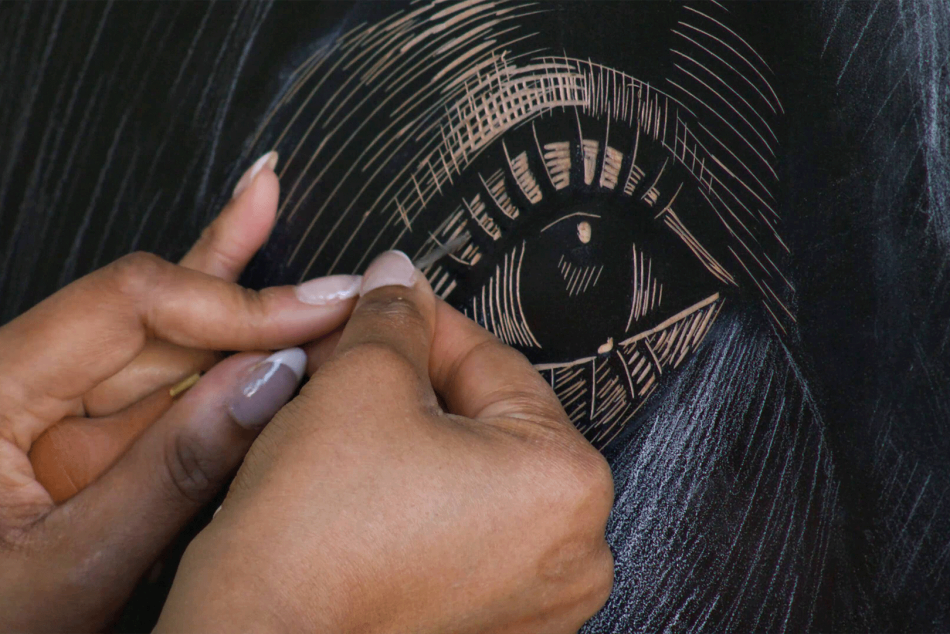

Video: Print Like a Great: Elizabeth Catlett

What happens when legacy, artistry, and womanhood collide? LaToya Hobbs creates a stunning woodcut portrait of Naima Mora, inspired by the life and work of legendary printmaker Elizabeth Catlett—Naima’s own grandmother.

Video: End as Beginning: Chinese Art and Dynastic Time

The A. W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts presented by Wu Hung (2019)

Video: Master Printmaker LaToya Hobbs Creates a Woodblock Print Inspired by Elizabeth Catlett

Master printmaker LaToya Hobbs creates a woodblock print portrait of Naima Mora, referencing the sculpture Naima created by Elizabeth Catlett.

Video: Blood Joining Blood: The Immersive in Caravaggio’s Malta

Sydney J. Freedberg Lecture on Italian Art presented by Keith Sciberras (2024)

Video: Inside the Corcoran’s Incredible Art Collection

From 1869 to 2014, the Corcoran Gallery of Art was one of the oldest art museums in the United States, reflecting the country’s move from the ashes of the Civil War into the 21st century.

Audio

Series

You may also like

Artworks

Explore our collection of nearly 160,000 works spanning the history of Western art.

Games and Interactives

Paint your own masterpiece, learn fun facts, or take an AI-powered journey through the collection.