Stories

Read, watch, or listen to inspiring stories about art and creativity.

Jump to:

Editor’s picks

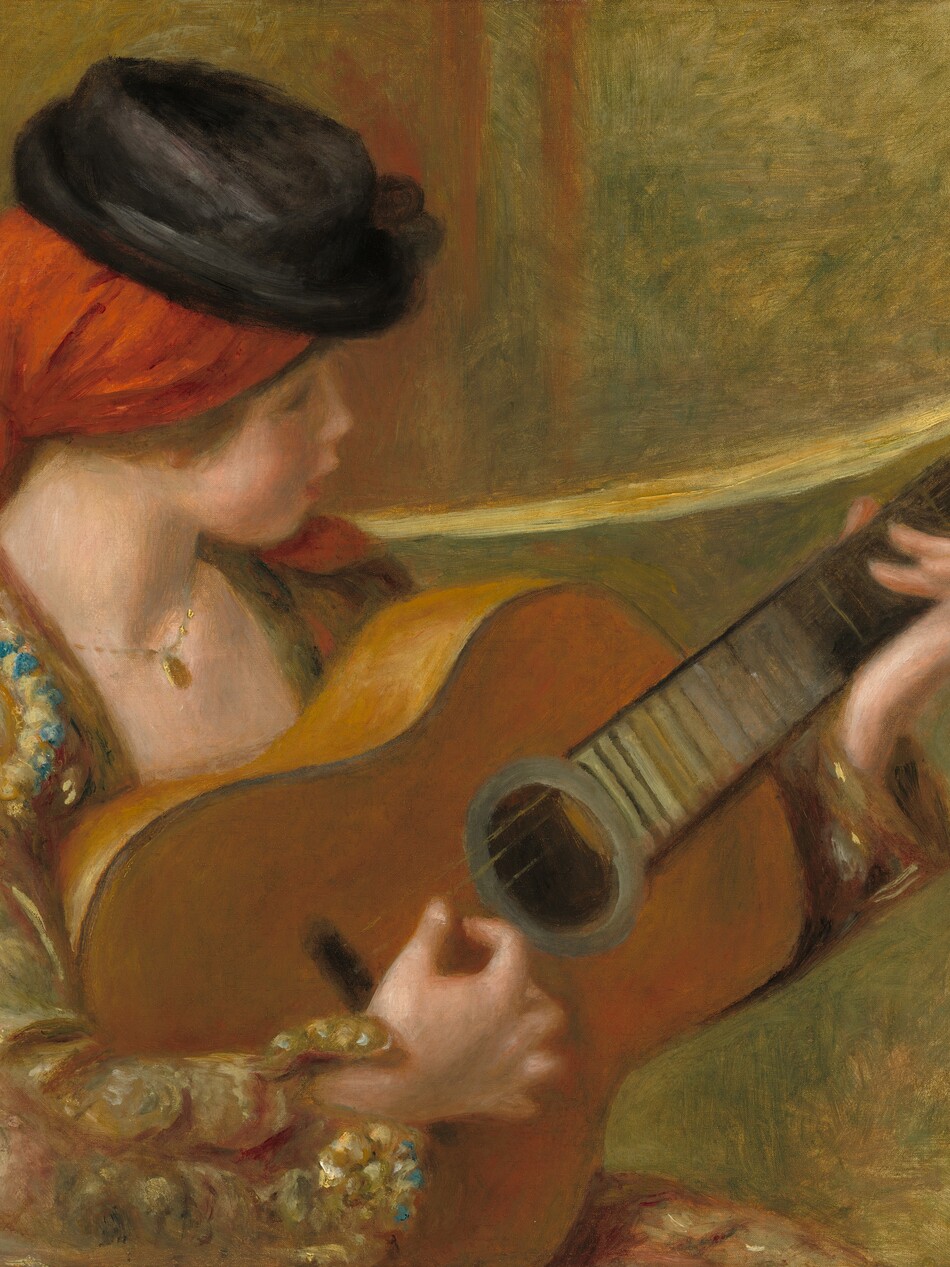

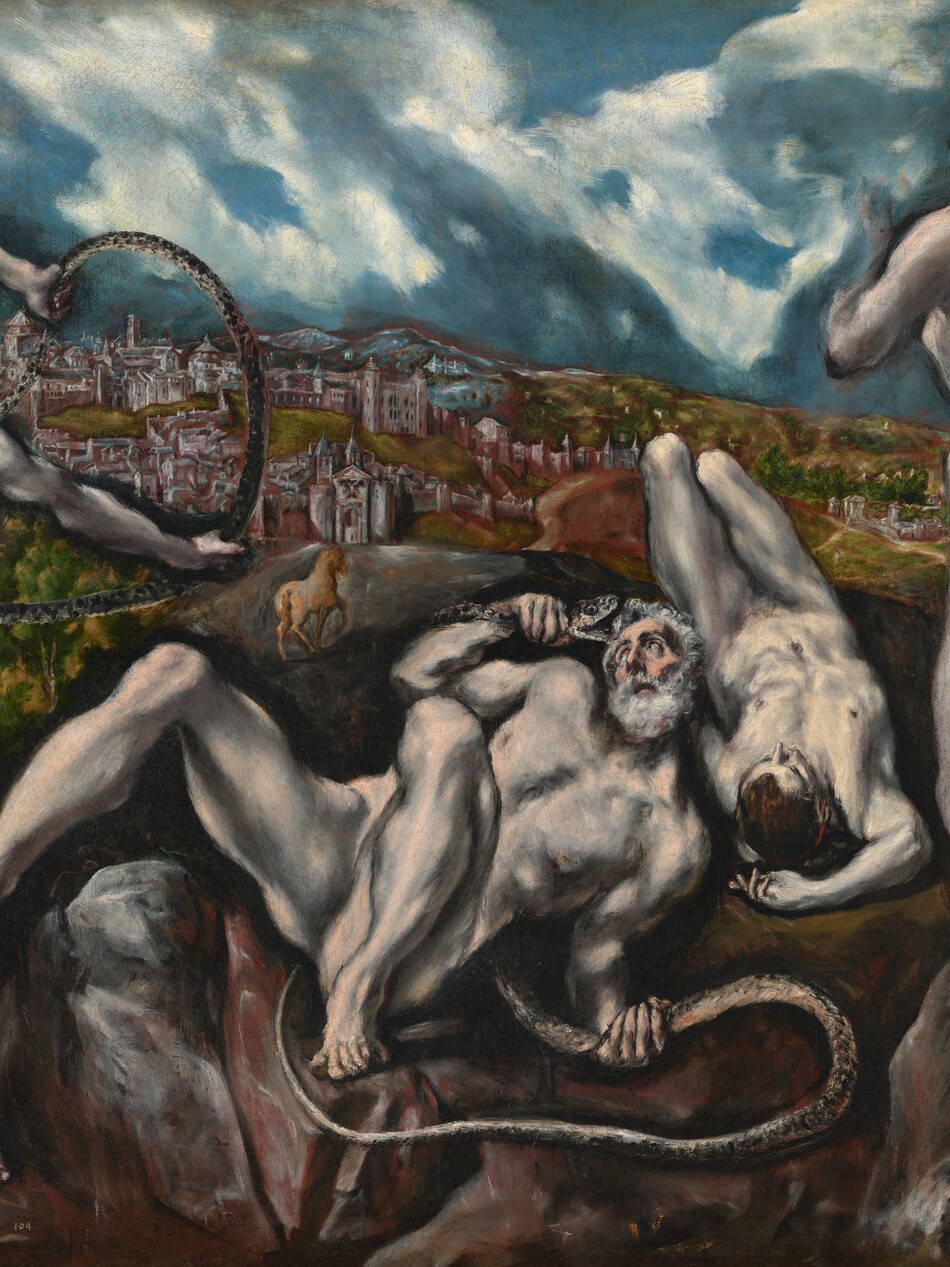

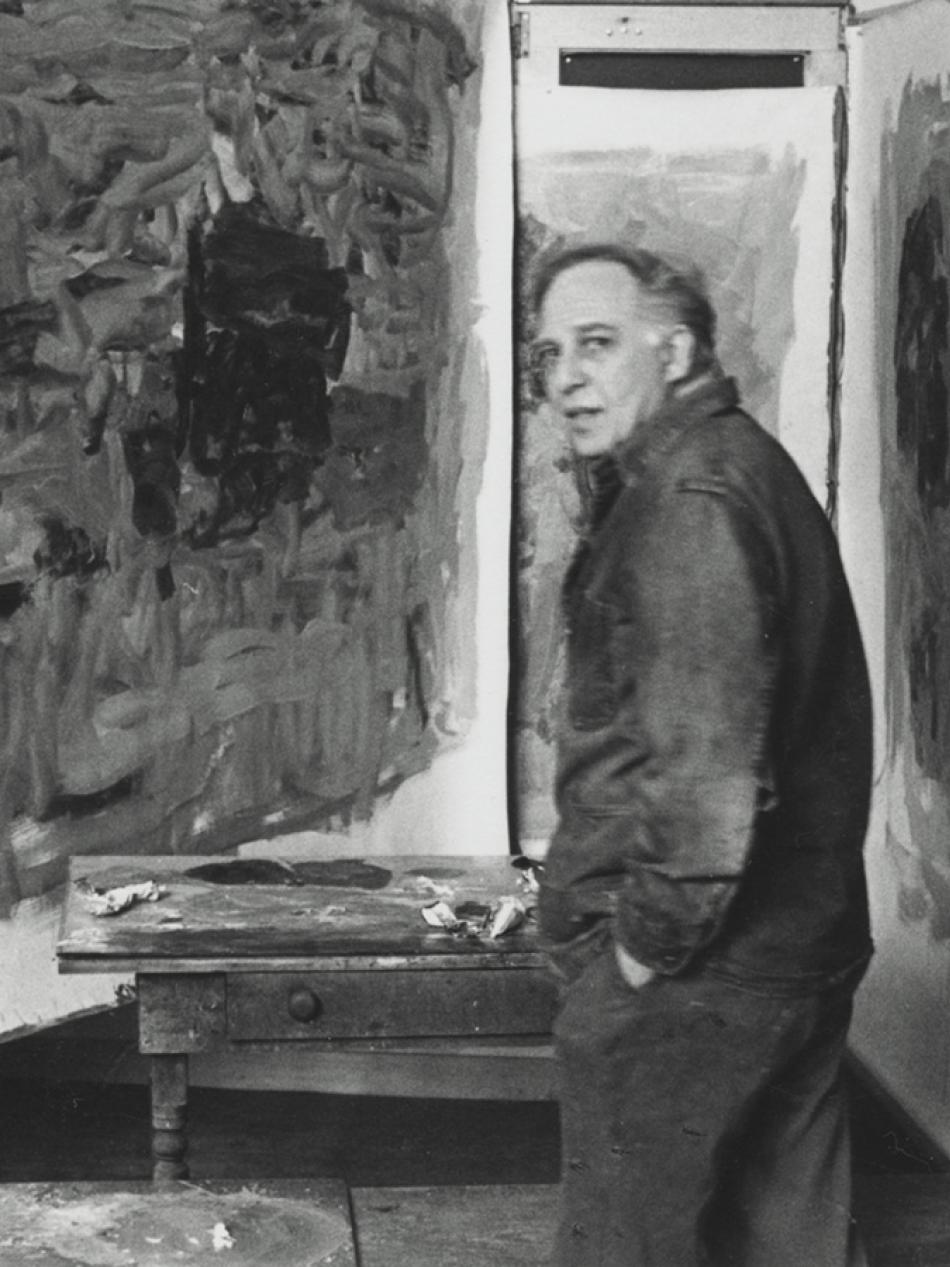

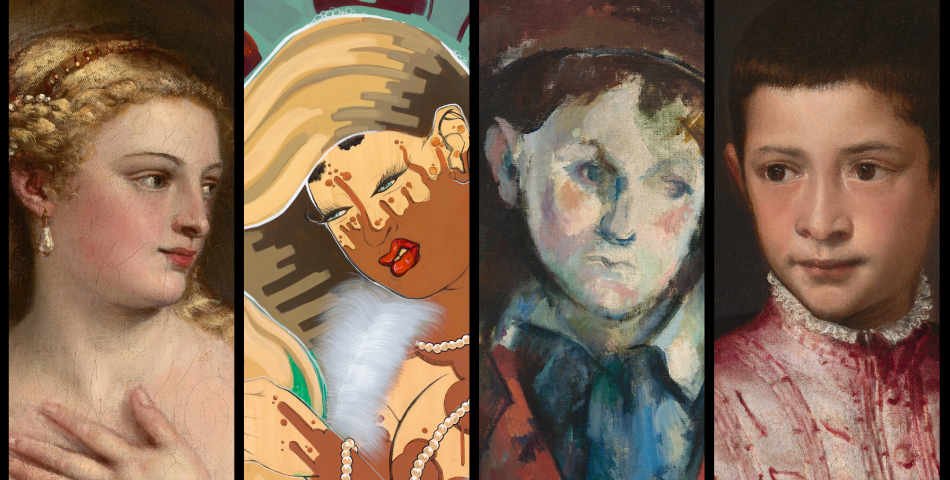

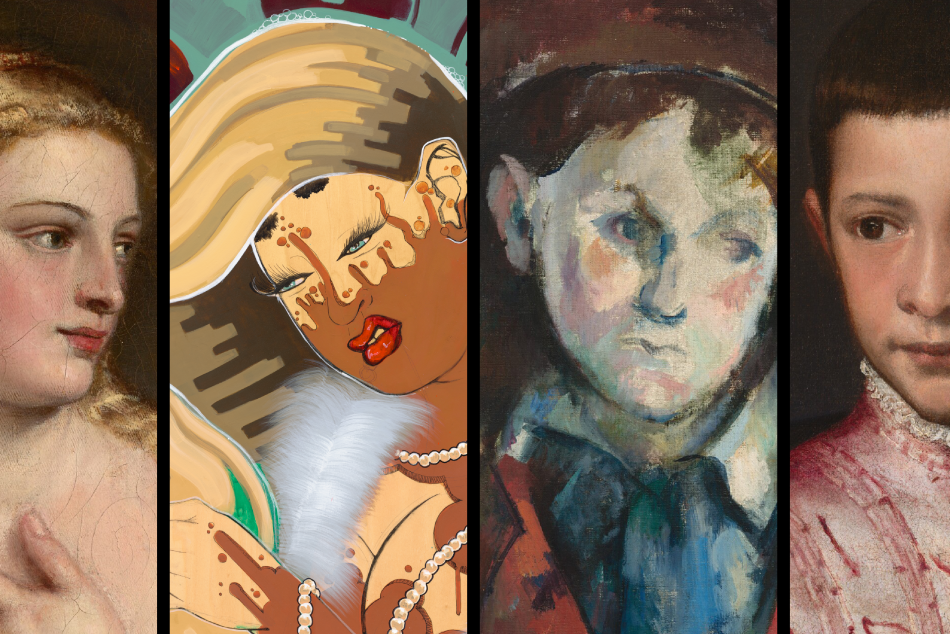

Interactive Article: Four Paintings Speak to Each Other Across Space and Time

See how Titian, Cezanne, and Rozeal. remix and reinterpret conventions for painting people.

Video: Look Closer: The Art of Devotion

Explore powerful stories of devotion, love, and artistic passion through iconic works of art—from religious masterpieces to revolutionary portraits.

Article: Summer in Art: Dive into Scenes of the Season

Artists from Mary Cassatt to Roy Lichtenstein have spent the warmer months making works about busy beaches, ripe raspberries, fresh flowers, and other signs of the season.

Articles

Look closer

Interactive Article: Four Paintings Speak to Each Other Across Space and Time

See how Titian, Cezanne, and Rozeal. remix and reinterpret conventions for painting people.

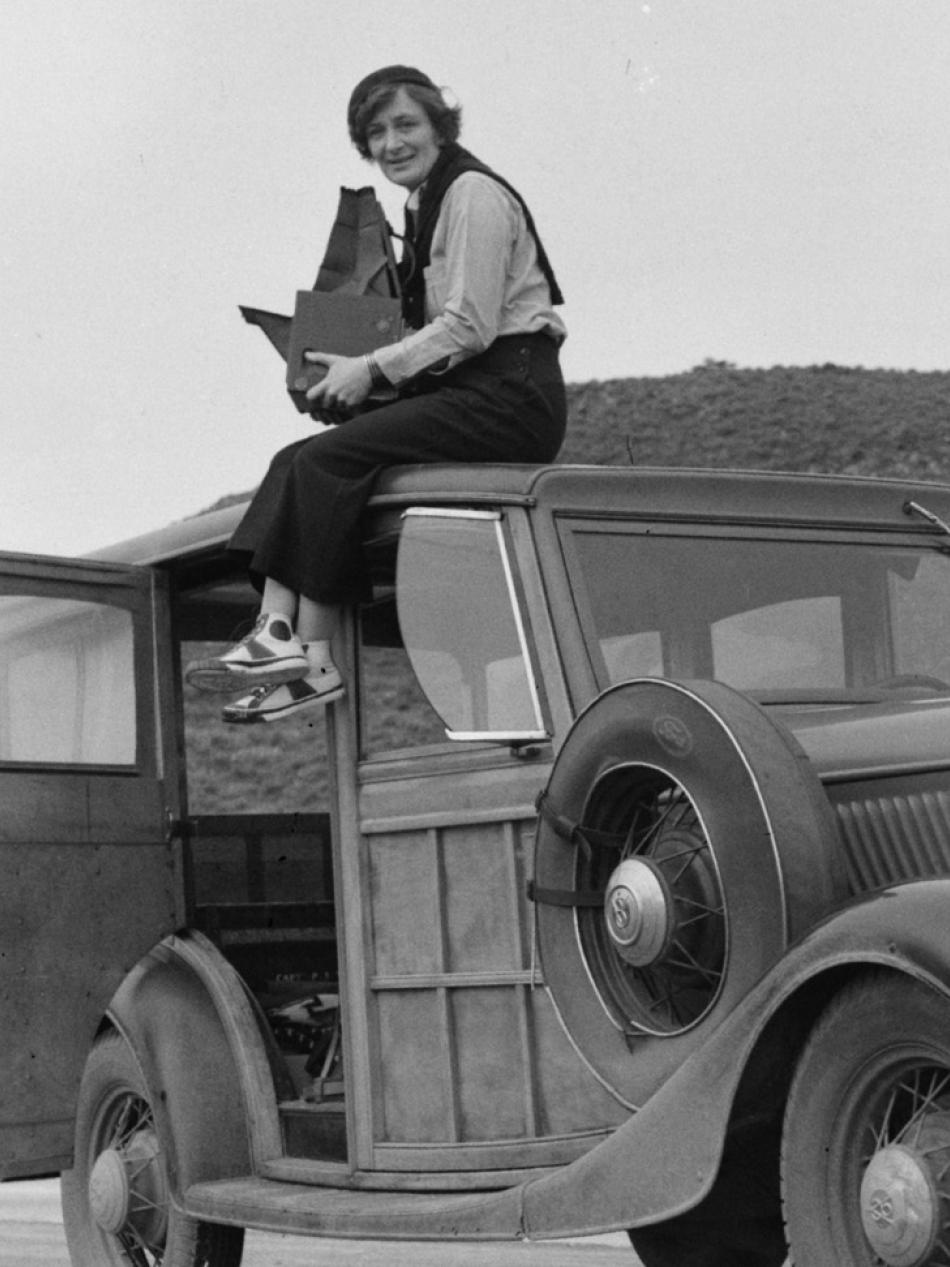

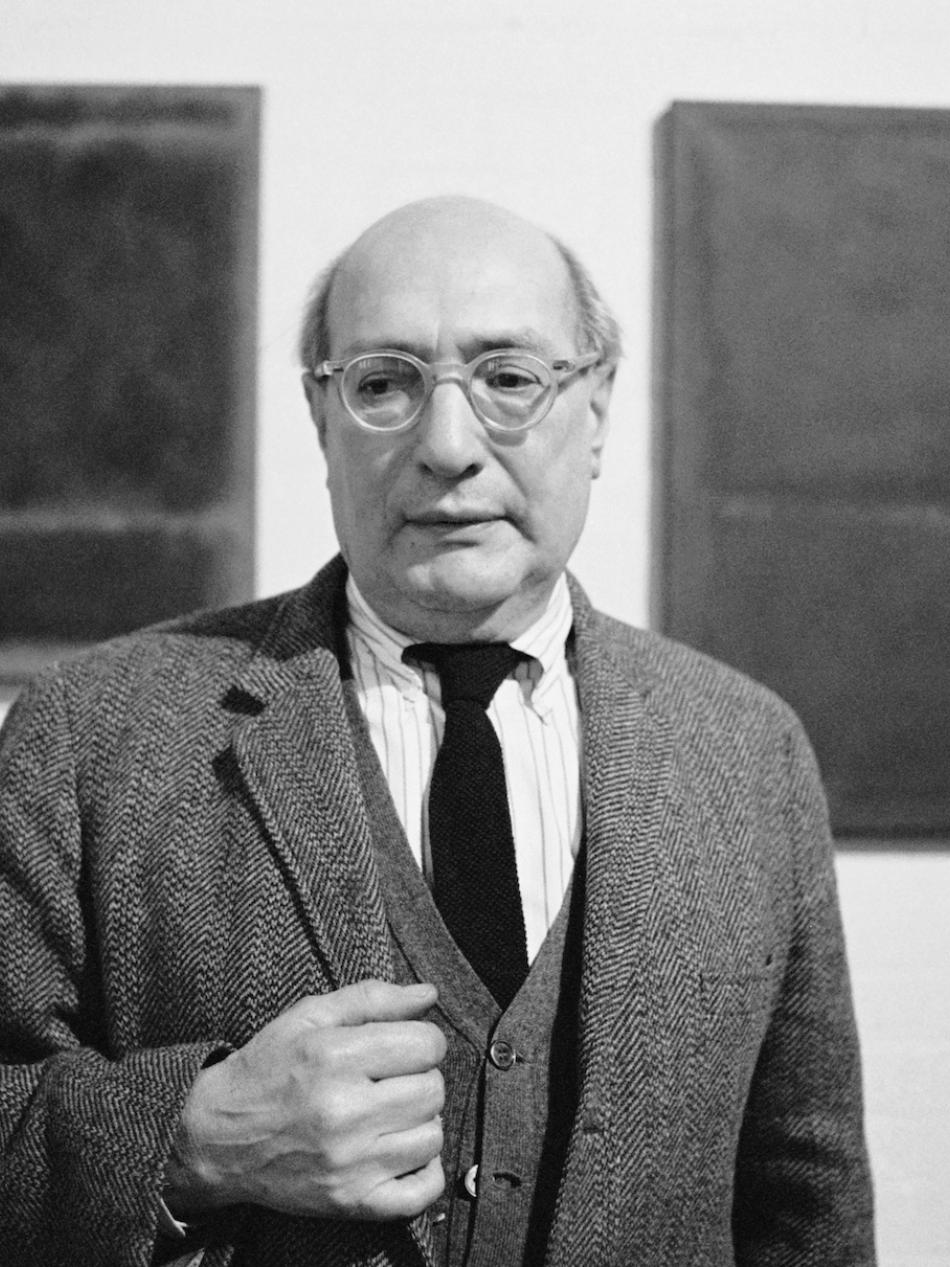

Article: Creating an Index of American Design

The US government once employed artists to draw pictures of designs from historical objects. The idea is reimagined by artists today.

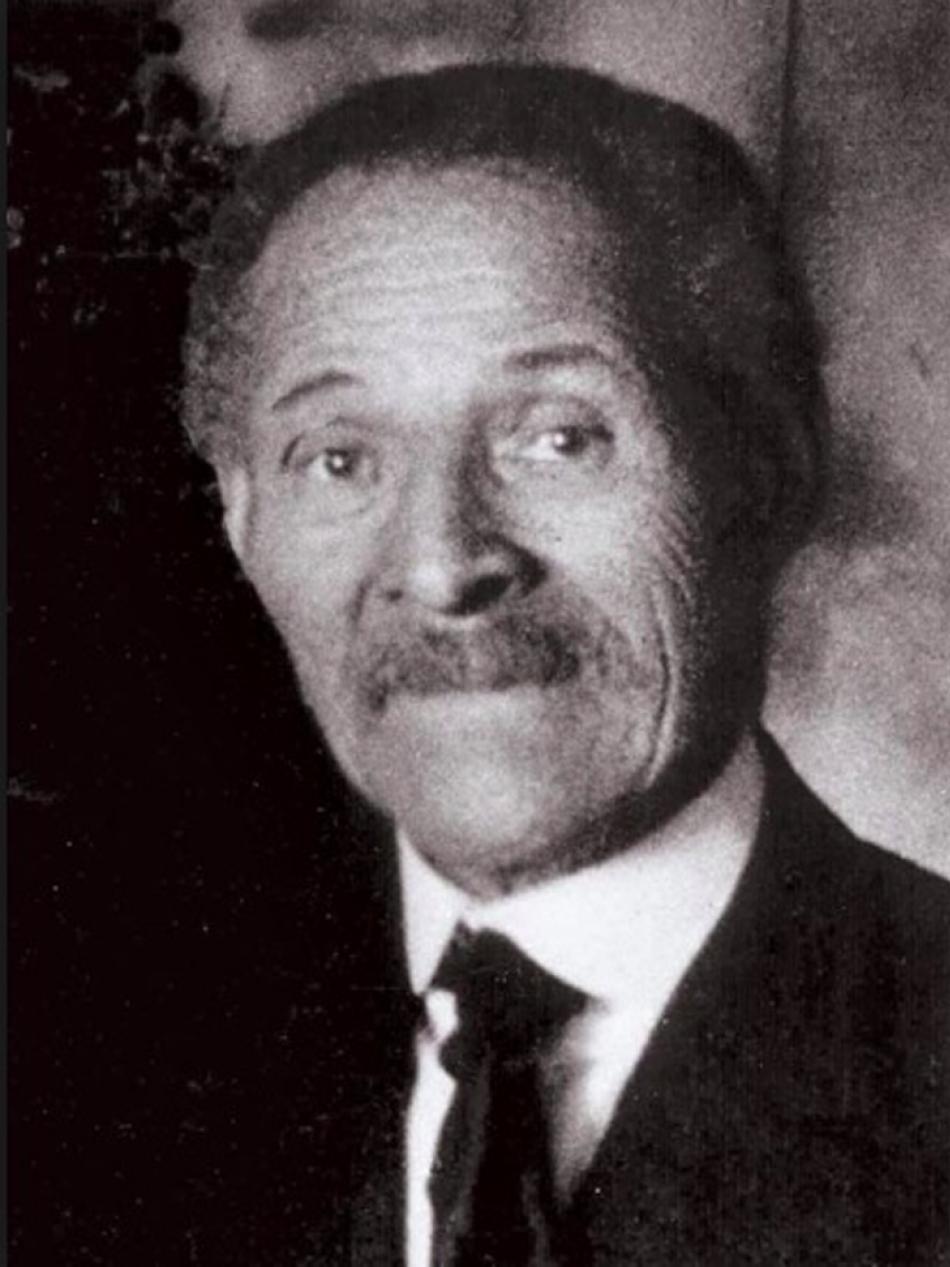

Interactive Article: How the Index of American Design Kickstarted Edward Loper’s Art Career

The acclaimed Delaware artist first brought his artistic ambitions to life drawing decorative art objects for the Work Progress Administration project.

Interactive Article: The Marvelous Details of Joris Hoefnagel’s Animal and Insect Studies

Scroll to discover tiny brushstrokes, hidden meanings, and the immense impact on our understanding of the natural world.

Article: Seven Highlights from the Index of American Design

Peer into the American past with a collection of Great Depression–era watercolors.

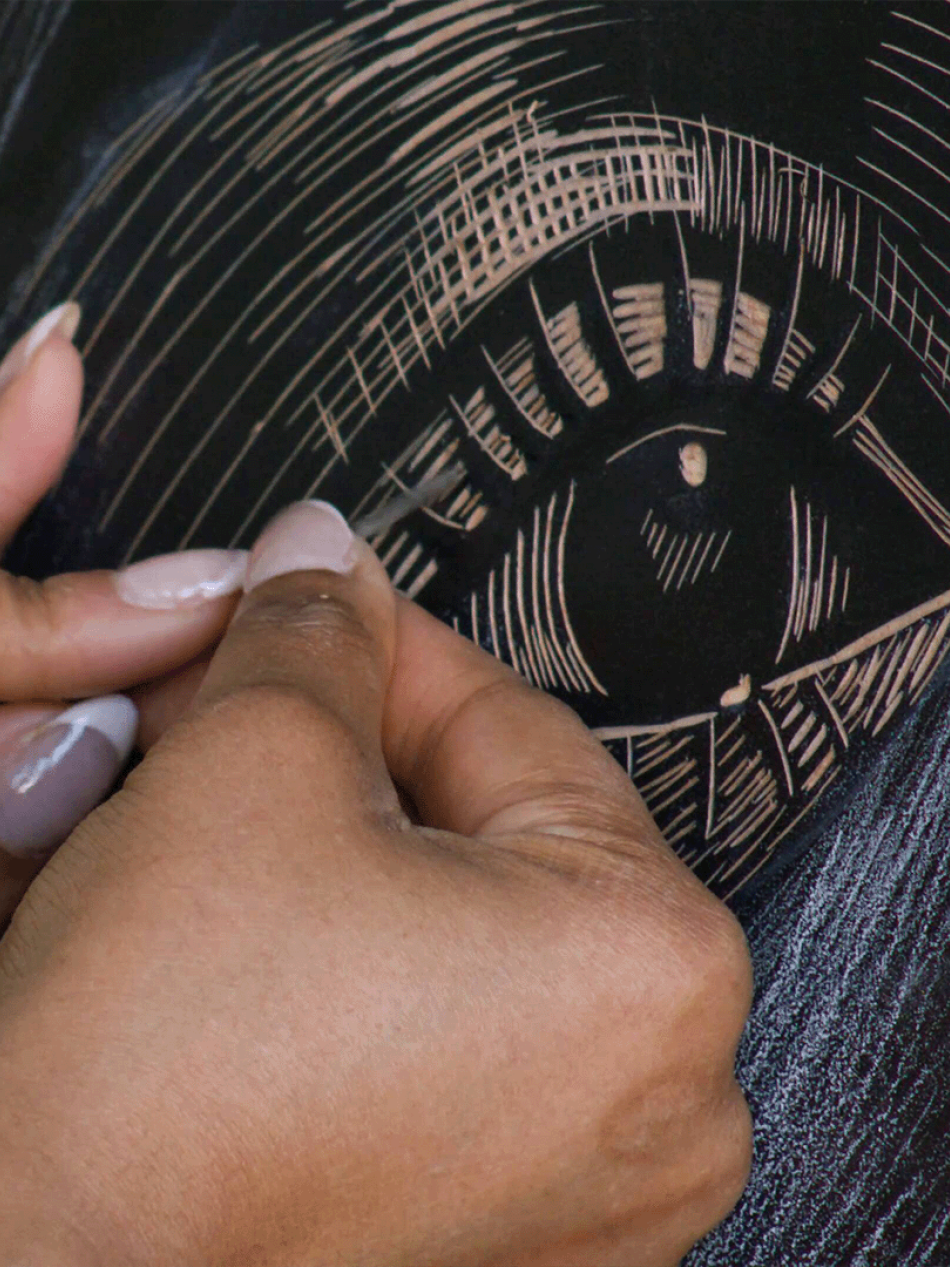

Article: Who Is Elizabeth Catlett? 12 Things to Know

Meet a groundbreaking artist who made sculptures and prints for her people.

Videos

Catch up on our latest videos

Video: He Painted Bugs Like Jewels — And Changed Science

At a time when bugs were mostly feared or ignored, Joris Hoefnagel's exquisite insect drawings invited wonder—and helped change the course of scientific illustration.

Video: Look Closer: The Art of Devotion

Explore powerful stories of devotion, love, and artistic passion through iconic works of art—from religious masterpieces to revolutionary portraits.

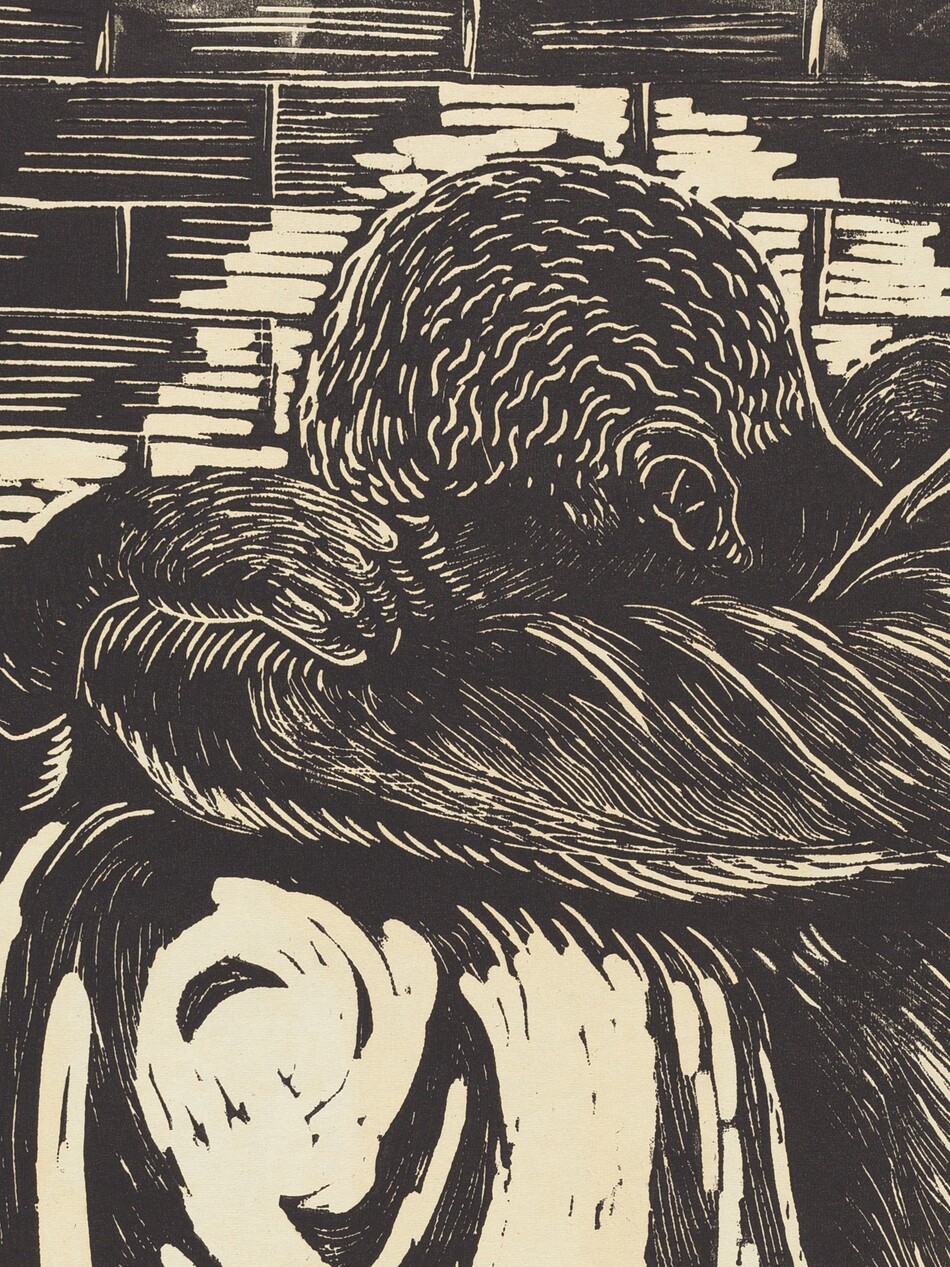

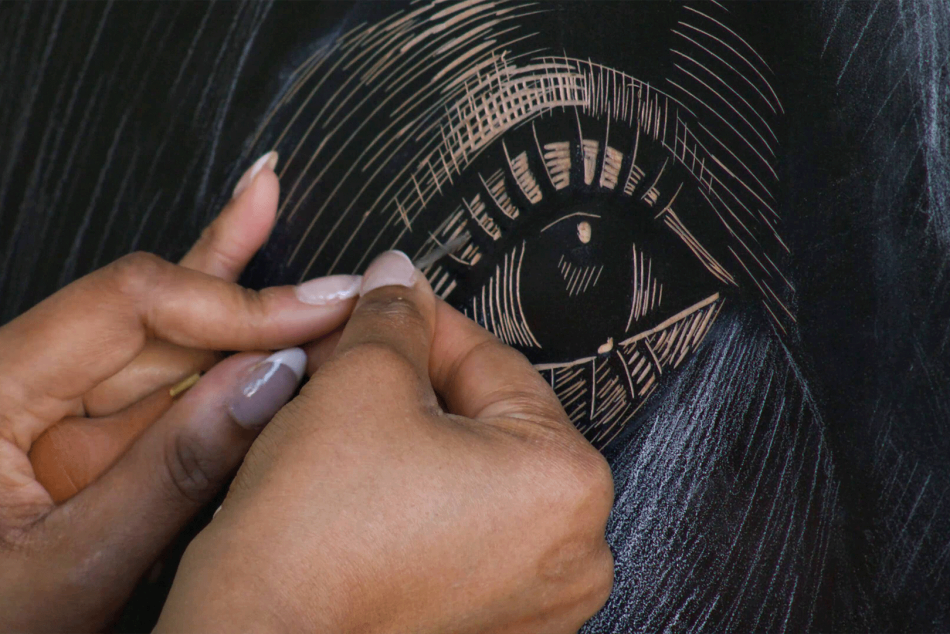

Video: Print Like a Great: Elizabeth Catlett

What happens when legacy, artistry, and womanhood collide? LaToya Hobbs creates a stunning woodcut portrait of Naima Mora, inspired by the life and work of legendary printmaker Elizabeth Catlett—Naima’s own grandmother.

Video: How This Photographer Used Selfies To Explore Layers Of Identity

Video essayist Nerdwriter helps us explore the extraordinary work of photographer Tseng Kwong Chi, whose iconic East Meets West series blends self-portraiture, performance, and satire.

Video: End as Beginning: Chinese Art and Dynastic Time

The A. W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts presented by Wu Hung (2019)

Video: Master Printmaker LaToya Hobbs Creates a Woodblock Print Inspired by Elizabeth Catlett

Master printmaker LaToya Hobbs creates a woodblock print portrait of Naima Mora, referencing the sculpture Naima created by Elizabeth Catlett.

Audio

Series

You may also like

Artworks

Explore our collection of nearly 160,000 works spanning the history of Western art.

Games and Interactives

Paint your own masterpiece, learn fun facts, or take an AI-powered journey through the collection.