Stories

Read, watch, or listen to inspiring stories about art and creativity.

Jump to:

Editor’s picks

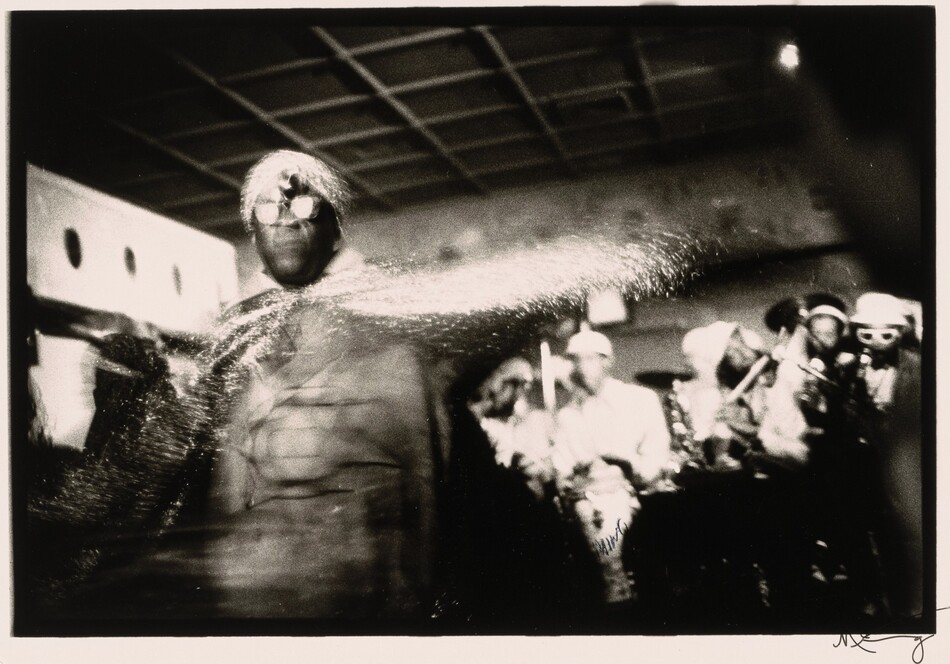

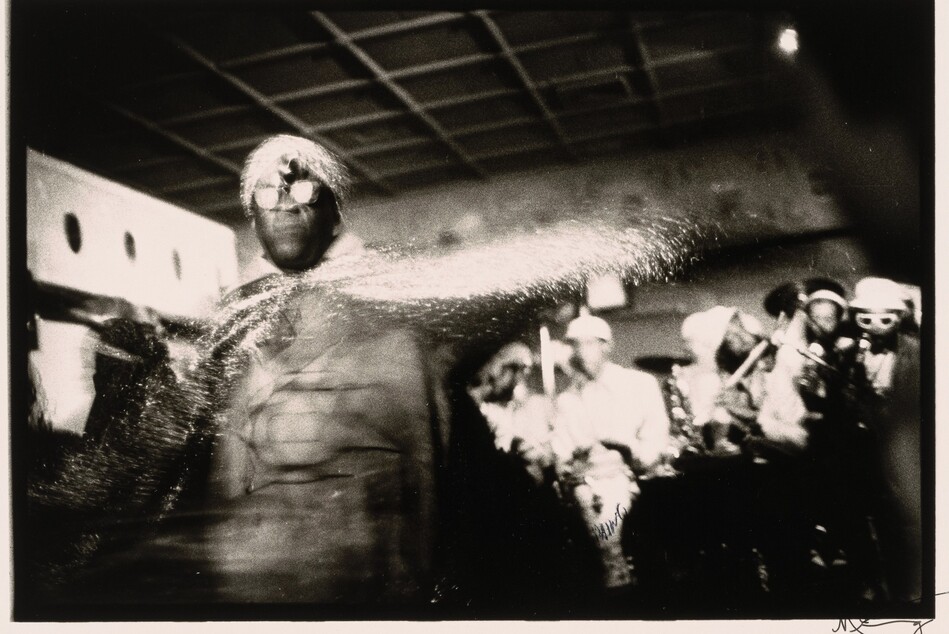

Article: What Is the Black Arts Movement? Seven Things to Know

Learn how the "cultural revolution in art and ideas" celebrated Black history, identity, and beauty.

Article: Smithsonian Scientists on How Artists Depicted Five Curious Creatures

Staff at the National Museum of Natural History helped us identify the animals and insects in our collection.

Video: What Do Kids REALLY Think About Art?

Sharp, hilarious, brutally honest kids react to some of our most iconic works.

Articles

Look closer

Article: Smithsonian Scientists on How Artists Depicted Five Curious Creatures

Staff at the National Museum of Natural History helped us identify the animals and insects in our collection.

Article: What Is the Black Arts Movement? Seven Things to Know

Learn how the "cultural revolution in art and ideas" celebrated Black history, identity, and beauty.

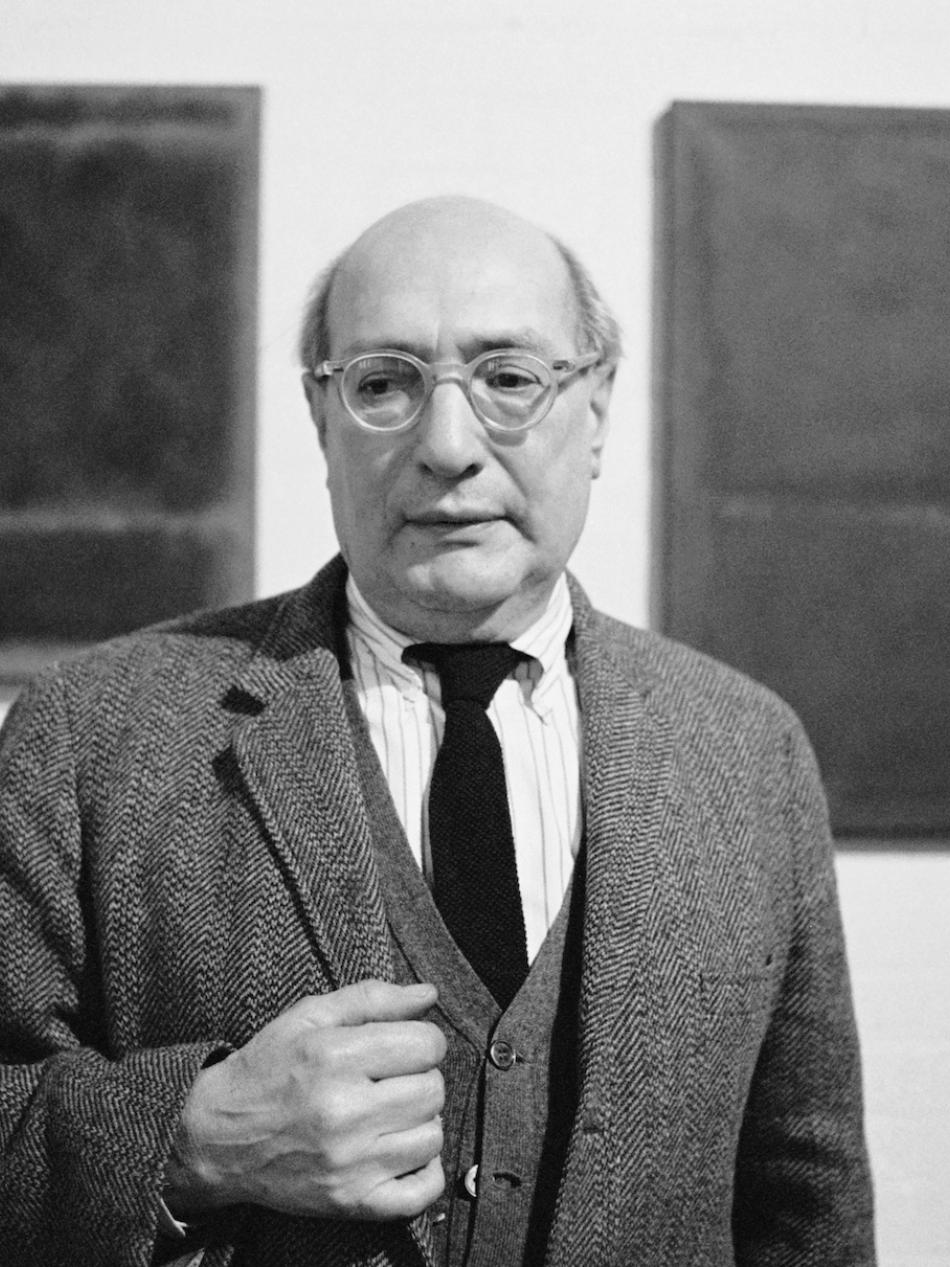

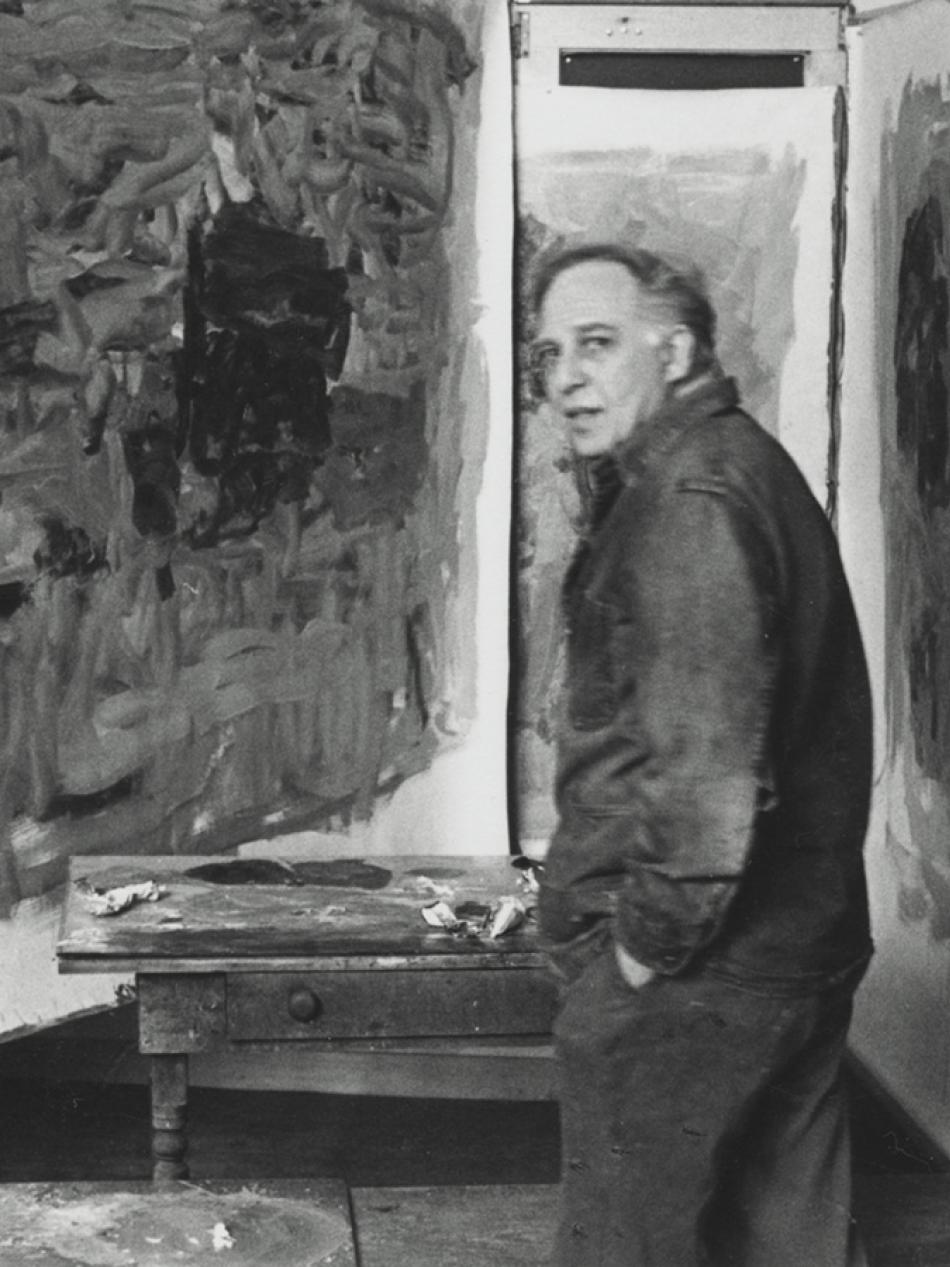

Article: In Plain Sight: What to Do When You Don’t “Get” Modern Art

Modern art can be intimidating. Here’s how to trust yourself and your own reaction to what you see.

Article: In Plain Sight: Finding Your First (Art) Love

How can we learn to fall in love with a work of art? From curators who share the works that sparked their lifelong passion for art.

Article: In Plain Sight: You Already Belong in This Museum

A podcaster explores her own museum anxieties and discovers how the people who work behind the scenes to help visitors feel at home—one conversation at a time.

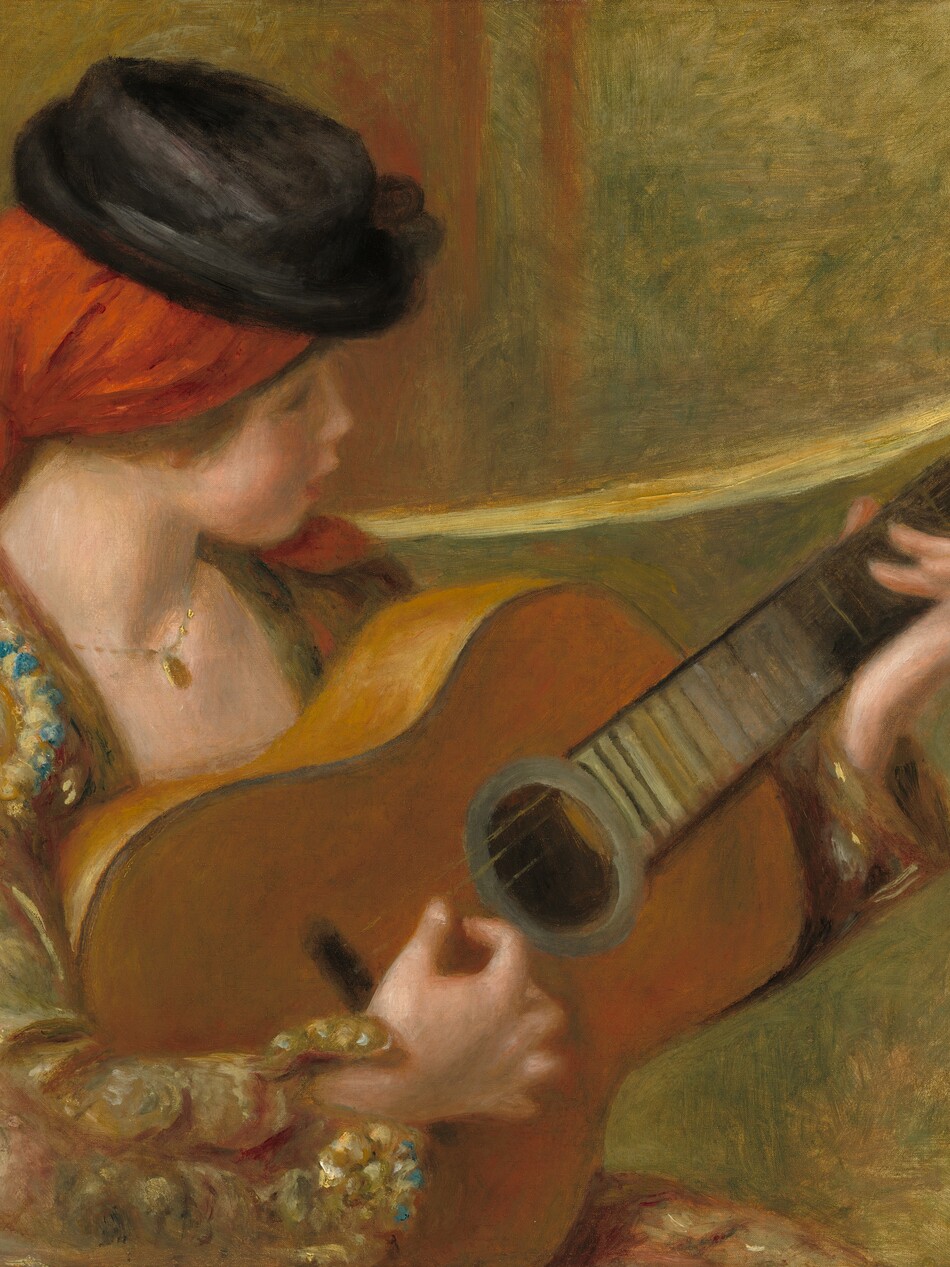

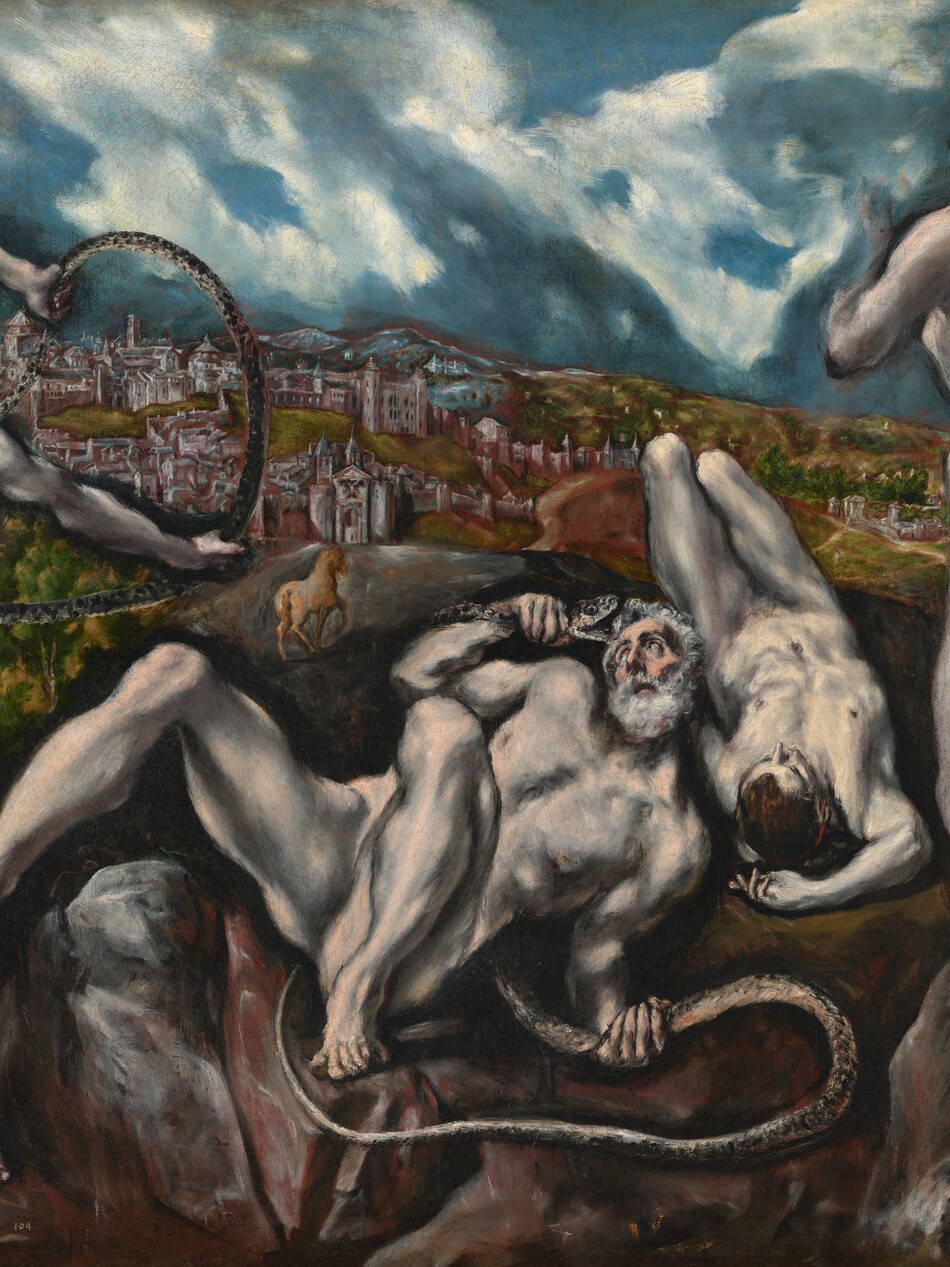

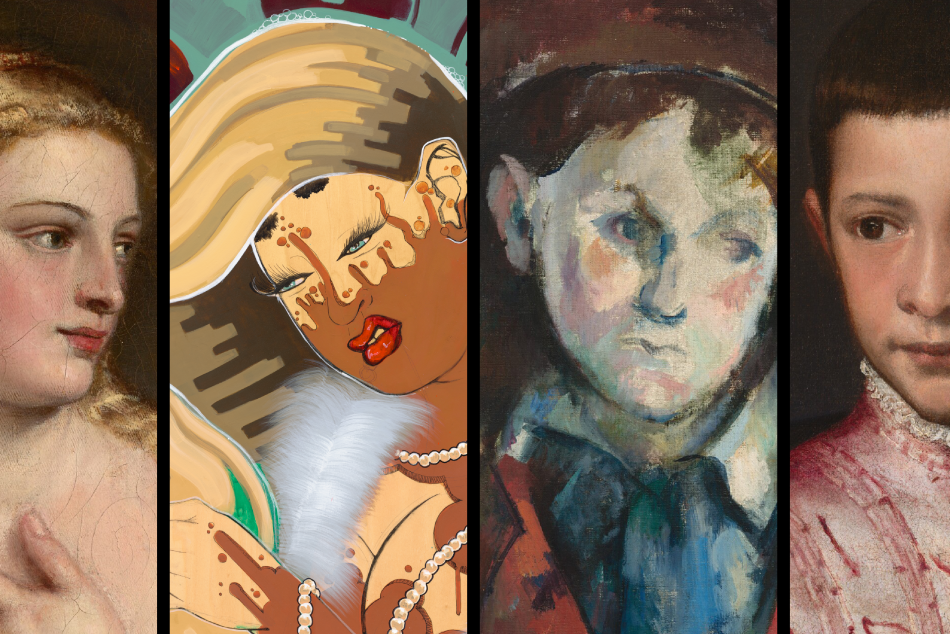

Interactive Article: Four Paintings Speak to Each Other Across Space and Time

See how Titian, Cezanne, and Rozeal. remix and reinterpret conventions for painting people.

Videos

Catch up on our latest videos

Video: What Do Kids REALLY Think About Art?

Sharp, hilarious, brutally honest kids react to some of our most iconic works.

Video: He Painted Bugs Like Jewels — And Changed Science

At a time when bugs were mostly feared or ignored, Joris Hoefnagel's exquisite insect drawings invited wonder—and helped change the course of scientific illustration.

Video: Look Closer: The Art of Devotion

Explore powerful stories of devotion, love, and artistic passion through iconic works of art—from religious masterpieces to revolutionary portraits.

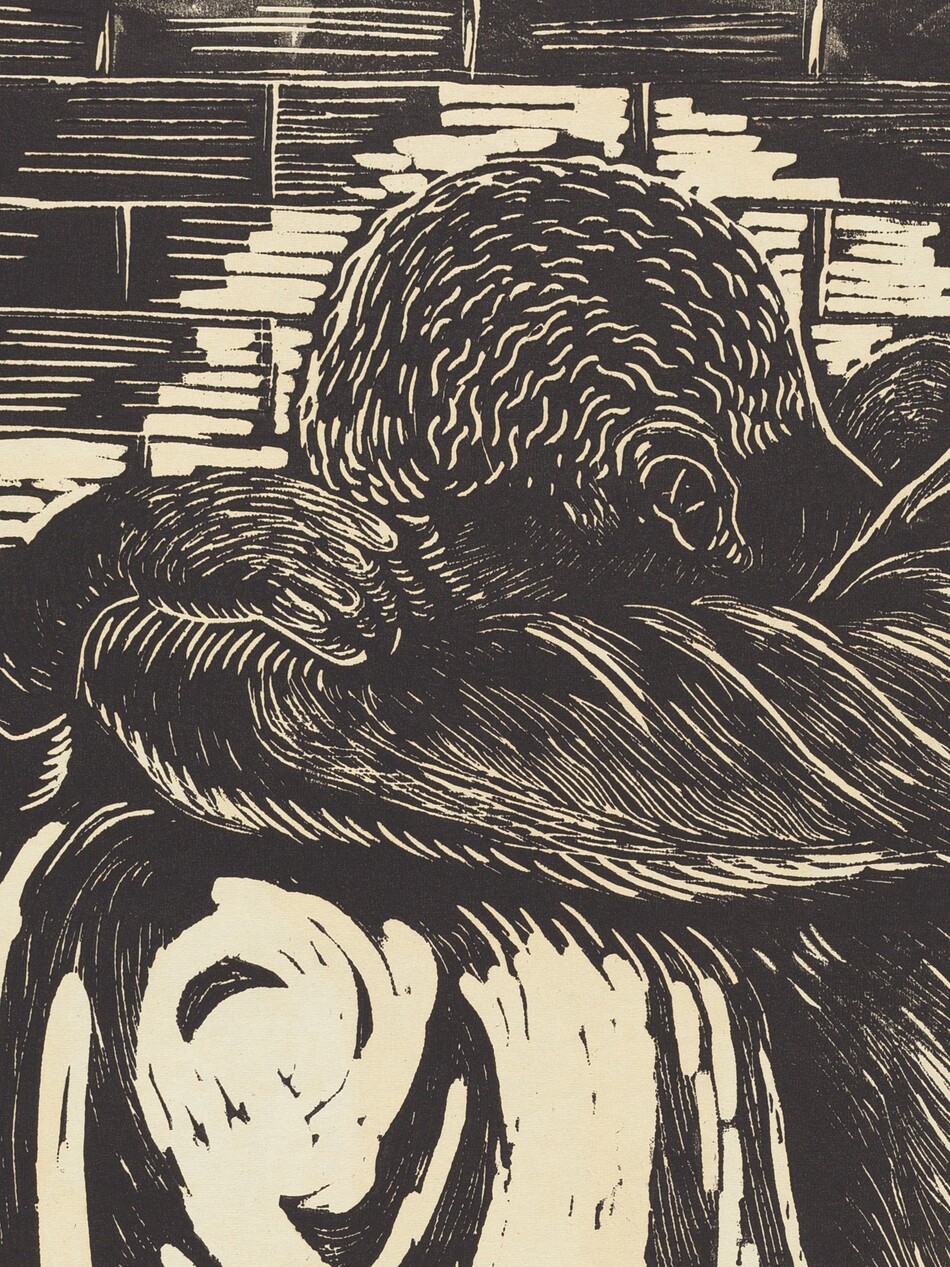

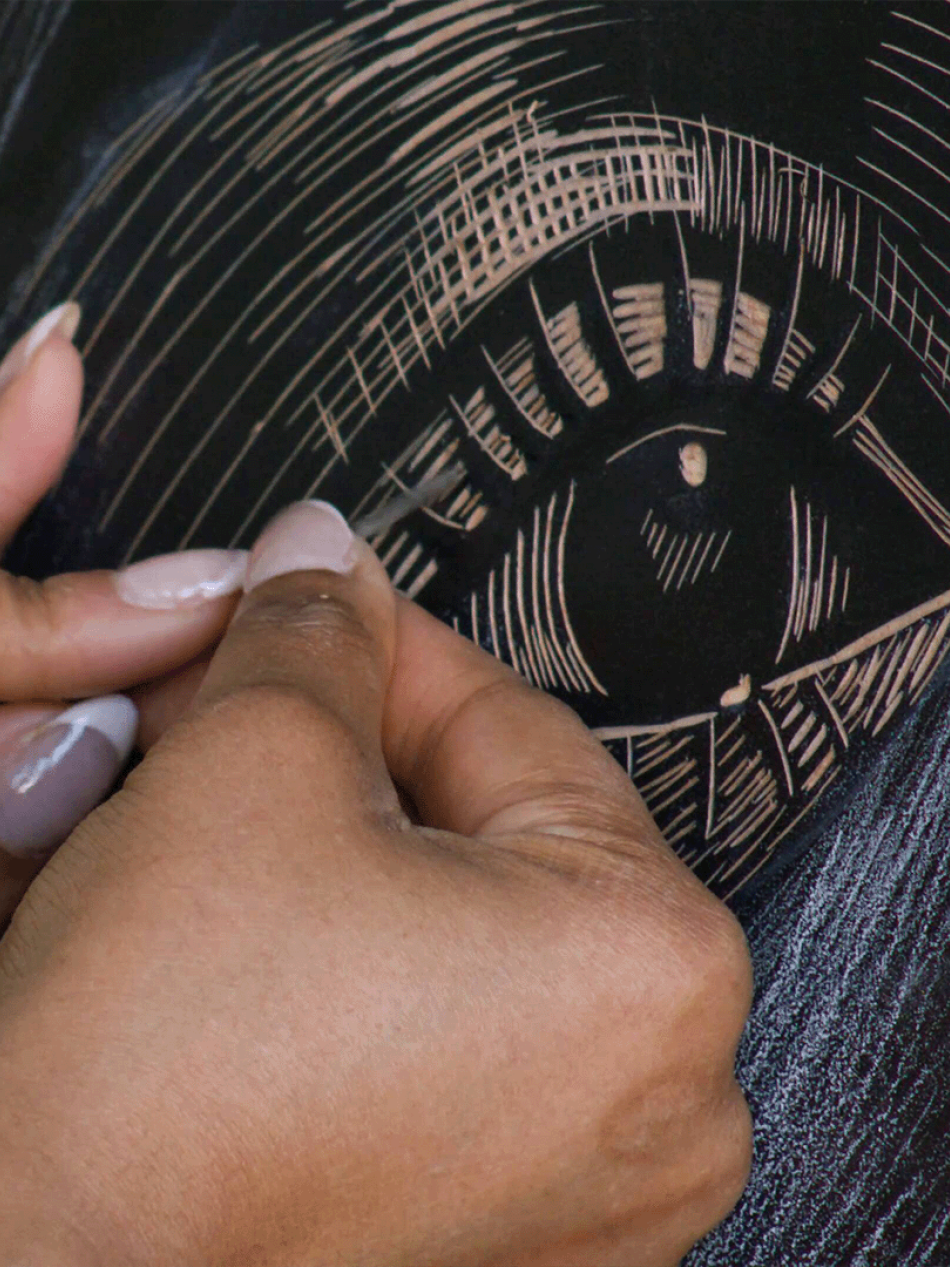

Video: Print Like a Great: Elizabeth Catlett

What happens when legacy, artistry, and womanhood collide? LaToya Hobbs creates a stunning woodcut portrait of Naima Mora, inspired by the life and work of legendary printmaker Elizabeth Catlett—Naima’s own grandmother.

Video: How This Photographer Used Selfies To Explore Layers Of Identity

Video essayist Nerdwriter helps us explore the extraordinary work of photographer Tseng Kwong Chi, whose iconic East Meets West series blends self-portraiture, performance, and satire.

Video: End as Beginning: Chinese Art and Dynastic Time

The A. W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts presented by Wu Hung (2019)

Audio

Series

You may also like

Artworks

Explore our collection of nearly 160,000 works spanning the history of Western art.

Games and Interactives

Paint your own masterpiece, learn fun facts, or take an AI-powered journey through the collection.