Claude Joseph Vernet: The Shipwreck

The Painting

The wind came out of nowhere, lifting the sea and slamming our ship into the rocky shore. A blanket of clouds quickly closed in—but for the ragged flashes of lightning, we were in the dark. With thunder blasting like cannons at close range, men leapt into the surf, towing a line and tying the ship to a rock, while I, along with my sons, slid down the rope line to safety. A drowning woman, pulled from the sea, lay half-dead on the beach as we came ashore, and another leaned into the wind, exhausted, crying out to the heavens.

Claude-Joseph Vernet, The Shipwreck, 1772, oil on canvas, Patrons' Permanent Fund and Chester Dale Fund, 2000.22.1

For the eighteenth-century imagination, this representation of a shipwreck was the equivalent of a modern movie, in full technicolor and stereo sound. French artist Claude Joseph Vernet (1714–1789) specialized in these stormy seascapes, often depicting sailing vessels in distress. His patrons and critics loved to imagine themselves within these wild scenes of destruction, battered by wind and spray, feeling the terror of the sublime. Paintings like this one were also thought of as vanitas, reminders of the transitory nature of life on earth.

Claude-Joseph Vernet, The Shipwreck, 1772, oil on canvas, Patrons' Permanent Fund and Chester Dale Fund, 2000.22.1

In Vernet’s Shipwreck, lightning spotlights a seaside town in the far distance and the breaking waves on the near shore. Vernet often portrayed changing weather and time of day (rain, lightning, sunsets, and moonlight), filtering light through clouds and mist to create the superb atmospheric effects for which he was famous. Here the artist used lively brushwork to create sparkling spray and moving clouds; in contrast, the foreground details are precise and tight—a sailor’s straining muscles, the blowing cape, the green bedroll and trunks, even a frightened dog.

Claude-Joseph Vernet, The Shipwreck, 1772, oil on canvas, Patrons' Permanent Fund and Chester Dale Fund, 2000.22.1

Through his use of strong diagonals, Vernet creates a vortex of motion in the lower half of the painting. He points the ship’s mast straight at the broken tree; from the tree, he leads the eye through the breaking wave down the cliff to the woman lying on the beach, and then circles back up along the rope line to the crow’s nest. The diagonal lightning bolt points directly to the center of action. This circular composition sets the boat, the water, and the sky into rolling, turbulent motion. Only the castle stands strong against the storm.

Claude-Joseph Vernet, The Shipwreck, 1772, oil on canvas, Patrons' Permanent Fund and Chester Dale Fund, 2000.22.1

What made Vernet's work so popular? Unlike his contemporaries, Vernet painted from nature, spending time in the country and at the seaside observing and sketching. His palette of blues, grays, greens, and ochres approximated the actual color of the sea, the sky, and the surrounding foliage. You only need to compare the naturalistic tonality of a Vernet landscape to one by his contemporary François Boucher to see the difference.

(left) Claude-Joseph Vernet, The Shipwreck, 1772, oil on canvas, Patrons' Permanent Fund and Chester Dale Fund, 2000.22.1

(right) François Boucher, The Love Letter, 1750, oil on canvas, Timken Collection, 1960.6.3

Vernet went to great lengths to gain real-life experience from which to render his subjects. He was reputed to have had himself bound to a ship’s mast during a storm so that he could experience a storm at sea. His grandson painted this episode.

A colleague wrote:

Vernet was sure to be on the beech [sic]; where he often prevailed on the watermen to put to sea, even during the heaviest storms, in a small open boat. By these means his mind becomes familiar to horrors, and his pencil capable of embodying...the elements in all their sublimity and grandeur.

Horace Vernet, Joseph Vernet Tied to a Mast in a Storm, c. 1822, Musée Calvet, Avignon, photograph by André Guerrand

The turbulent Shipwreck contrasted sharply with its paired mate, or pendant, Mediterranean Coast by Moonlight. The scene shown here, The Night, A Seaport by Moonlight, probably resembles the long lost Mediterranean Coast. This serene moonlit scene was "beautiful" in contrast to the Shipwreck's dark image of the "sublime."

(top) Claude-Joseph Vernet, The Shipwreck, 1772, oil on canvas, Patrons' Permanent Fund and Chester Dale Fund, 2000.22.1

(bottom) Claude Joseph Vernet, The Night: A Seaport by Moonlight, unknown date, Musée du Louvre, Paris, © Réunion des Musées Nationaux

Vernet often made pairs of paintings, even sets of four canvases, contrasting times of day with different weather effects.

(top left) Claude Joseph Vernet, The Four Parts of the Day: Morning or Fishing, 1762, Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon, © Réunion des Musées Nationaux, photograph by Daniel Arnaudet

(top right) Claude Joseph Vernet, The Four Parts of the Day: Noon or the Storm, 1762, Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon, © Réunion des Musées Nationaux, photograph by Daniel Arnaudet

(bottom left) Claude Joseph Vernet, The Four Parts of the Day: Evening or Sunset, 1762, Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon, © Réunion des Musées Nationaux, photograph by Daniel Arnaudet

(bottom right) Claude Joseph Vernet, The Four Parts of the Day: Night or Moonlight, 1762, Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon, © Réunion des Musées Nationaux, photograph by Daniel Arnaudet

The Artist

Claude Joseph Vernet was the most famous and successful landscape and marine painter in eighteenth-century France. Admired for his ability to combine the spectacular atmospheric effects of sky and weather with a detailed, lively handling of foreground figures, Vernet received important commissions throughout his career from the reigning King of France, Louis XV, and from nobles and diplomats throughout Europe and Russia.

Benedict Alphonse Nicolet after Charles-Nicolas Cochin II, Claude Joseph Vernet, 1781, etching on laid paper, Gift of John O'Brien, 1989.84.15

Born in 1714 in Avignon, France, Vernet came from a family of artists. His father, a minor decorative painter, gave Vernet his first lessons in drawing; Vernet later worked with a master painter in Avignon. In private collections there and in nearby Aix-en-Provence, Vernet would likely have studied works attributed to seventeenth-century masters Claude Lorrain, Salvator Rosa, and Gaspard Dughet.

Claude-Joseph Vernet, Trees Reflected in a Brook, pen and brown ink, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1984.78.1

Like Claude and other artists of the time, Vernet traveled to Italy to complete his artistic education. The young Vernet was immediately taken by the beauty of the Italian countryside, writing back to Avignon in 1734: "One finds the most beautiful views in the world for drawing [here in Rome]." Vernet loved to sketch en plein air. The English painter Sir Joshua Reynolds noted this, writing to a fledgling painter: "Carry your palette and pencils to the waterside. This was the practice of Vernet...he showed me his studies in colours...the impression is warm from Nature."

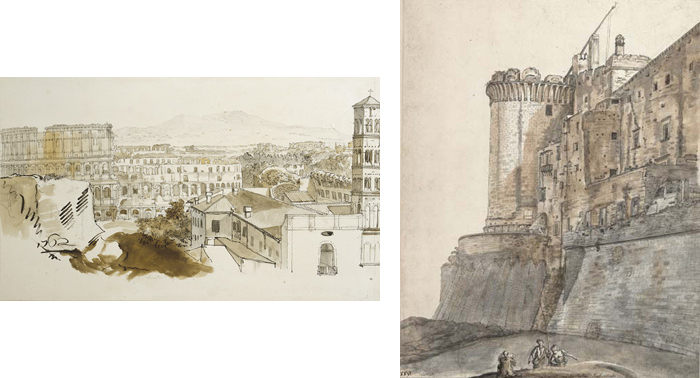

(left) Claude Joseph Vernet, Panorama of Rome, with Colosseum, unknown date, Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna

(right) Claude Joseph Vernet, The Artist Drawing the Castel Nouvo, Naples, unknown date, Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna

Vernet was soon overwhelmed with commissions from the diplomatic community in Rome and from the British, who considered his work the perfect souvenir of the Grand Tour. Vernet lived in Rome for the next twenty years, painting softly lit scenes of Tivoli, the Roman countryside, and the Neapolitan coast, as well as seascapes, both calm and stormy. While he occasionally accepted commissions for paintings of specific locations, he preferred to create imaginary scenes, combining dramatic skies and land- and seascapes with detailed foreground figures.

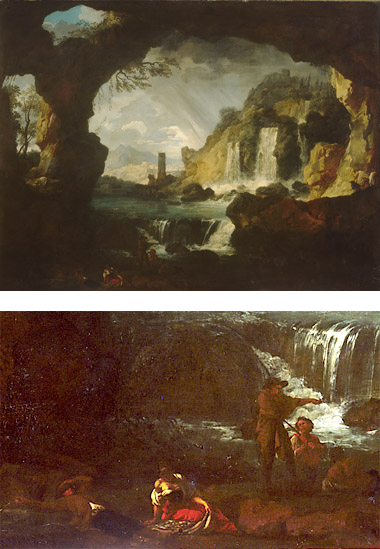

Claude Joseph Vernet, View of the Small Waterfalls at Tivoli, unknown date, Musée de la Marine, Paris, © Réunion des Musées Nationaux

In 1753 Vernet returned to France to begin paintings commissioned by Louis XV. He spent the next twelve years traveling the French coast, creating scenes of French military and commercial seaports. These grand seascapes, considered masterpieces, are collectively called the Ports of France. Vernet painted not only the specific topography but also included the daily activities in each port, giving the paintings an almost scientific interest typical of the age of Enlightenment.

Although Louis XV commissioned some two dozen Ports of France, Vernet completed only fifteen. Year after year he exhibited them in the Paris Salon where they were praised by contemporary critics and viewers.

Claude Joseph Vernet, The Port of Sète, 1775, Musèe de la Marine, Paris, © Réunion des Musées Nationaux

In 1762 Vernet settled in Paris, where he would become best known for his often stormy marine paintings that expressed the sublime in nature. Critics praised Vernet's ability to study the natural world and capture it realistically on canvas, while suggesting a divine presence through the use of dramatic lighting, ravaged landscape, and atmospheric effects. Vernet's work captivated French philosopher Denis Diderot, who compared it to the finest history painting, at the time the most respected subject for art. Diderot liked to “visit” Vernet’s paintings as if they were actual sites, praising the exceptional points of view Vernet presented on canvas.

Thomas Ryder, Diderot, engraving on laid paper, Gift of John O'Brien, 1990.56.9

Visions of the Sea

A century before French artist Claude Joseph Vernet created his renowned seascapes, marine art had reached its peak in the Netherlands. Paintings of calm Dutch estuaries, crowded fleets in harbor, and ships tossed on stormy waters filled private homes and public buildings throughout the country. Surrounded by water, the Dutch Republic thrived because of its mastery of the seas: merchants sent trading ships throughout the world, bringing back all manner of common and luxury goods that fueled the booming economy. As the middle class grew and prospered, many became patrons of the arts, and seascapes were among the most popular subjects collected.

(top left) Claude-Joseph Vernet, The Shipwreck, 1772, oil on canvas, Patrons' Permanent Fund and Chester Dale Fund, 2000.22.1

(top right) Ludolf Backhuysen, Ships in Distress off a Rocky Coast, 1667, oil on canvas, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1985.29.1

(bottom left) Jan van Goyen, View of Dordrecht from the Dordtse Kil, 1644, oil on panel, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1978.11.1

(bottom right) Aelbert Cuyp, The Maas at Dordrecht, c. 1650, oil on canvas, Andrew W. Mellon Collection, 1940.2.1

Simon de Vlieger was among the most popular marine artists in seventeenth-century Holland. He painted "parades" of ships in harbor, calm estuary scenes like this one, and stormy shipwrecks. He is best known for his sensitivity to the constantly changing weather along the coast and inland canals of Holland. In Estuary at Dawn, painted between 1640 and 1645, he uses a subtle range of grays and blues to capture light filtering through drifting clouds and boats moving in deep and shallow waters. De Vlieger's dramatic use of atmospheric lighting to create silvery skies and shimmering water, and his tight pictorial design distinguished his work from his colleagues’.

Simon de Vlieger, Estuary at Dawn, c. 1640/1645, oil on panel, Patrons’ Permanent Fund and The Lee and Juliet Folger Fund in memory of Kathrine Dulin Folger, 1997.101.1

Throughout the history of art, a seafaring ship has been a metaphor for man's journey through life. For the Dutch patron, a quiet scene like Estuary at Dawn celebrated the harmony of man in the natural world, working and prospering with God's blessing. Here two workers apply pitch (tar) to the hull of a ship as dark smoke rises from a vat of hot pitch nearby. The jetty on the sandbar balances the rowboat, and in the near distance a large ship fires off a salute. As dawn's rays break through drifting clouds, all is in balance. For the Dutch, particularly in the first half of the seventeenth century, life was good: the sea with all its resources brought a "Golden Age" of prosperity and calm to the nation.

Simon de Vlieger, Estuary at Dawn, c. 1640/1645, oil on panel, Patrons’ Permanent Fund and The Lee and Juliet Folger Fund in memory of Kathrine Dulin Folger, 1997.101.1

To create this feeling of calm, de Vlieger composed the picture in horizontal bands, echoing the quiet morning activity of seamen who were up early to begin a day's work. The dark, flat clouds above the narrow rowboat, the sandbar extending out at low tide, and the low horizon line all contribute to the painting's serene effect.

In contrast, Vernet's Shipwreck, with its sharp diagonals and churning clouds and water, sent a message about the precariousness of life and the necessity of having faith in God to survive difficult times.

(top) Simon de Vlieger, Estuary at Dawn, c. 1640/1645, oil on panel, Patrons’ Permanent Fund and The Lee and Juliet Folger Fund in memory of Kathrine Dulin Folger, 1997.101.1

(bottom) Claude-Joseph Vernet, The Shipwreck, 1772, oil on canvas, Patrons' Permanent Fund and Chester Dale Fund, 2000.22.1