Suffused with effortless grace, the model in Fragonard’s Young Girl Reading embodies the cultured lifestyle treasured by high society in pre-Revolutionary France. She is absorbed in a small book that she holds in her delicately curled right hand—pinky extended—reflecting the vogue for portable novels that flourished among the elite late in the century (such as Voltaire’s satirical Candide or Rousseau’s sentimental Julie ou la nouvelle Héloïse).

Young Girl Reading is visually delectable. The model, shown in profile, rests her left arm on a wooden rail and leans back against a plush, oversized cushion. Strong light from above softens the pink of her cheeks (one 19th-century critic compared them to the skin of a peach) and casts her shadow against the cushion and the wall. The fashionable lemon-yellow dress, accented with a white ruff and cuffs, stands out brilliantly against the unadorned interior. Lilac ribbons adorn the figure’s bodice, neck, and coiffed hair, echoing the cushion’s purplish tones.

Fragonard’s astounding brushwork is as much the subject of this painting as the young woman reading is. He has carefully delineated her face, but her dress, ribbons, and the cushion are loosely brushed in large, vigorous, unblended strokes. The artist’s brio is further conveyed by the summarily sketched book and the edging of the girl’s collar, the latter of which he executed—one imagines in a single, great flourish—with the handle of the brush. The vivid brushwork draws attention to Fragonard’s virtuosity, but it also suggests the mental transport experienced by the figure of the self-contained reader.

Young Girl Reading is linked to a series of Fragonard paintings known as portraits de fantaisie (imaginary portraits) that upended established conventions of portraiture and was the subject of a National Gallery of Art exhibition in 2017. Executed very quickly—purportedly in an hour—these compositions featured half-length single figures on canvases of very similar dimensions. Working feverishly, Fragonard used his models as a springboard for his artistic imagination. Unlike the portraits de fantaisie, however, Young Girl Reading functions less as a portrait concerned with accurately capturing the sitter’s likeness or character than as a genre painting (a scene of everyday life), which became immensely popular in 18th-century France.

About the Artist

Had Jean Honoré Fragonard followed the traditional path of 18th-century artists, he well might have become the French king’s “first painter” and director of the nation’s acclaimed Académie royale. Born in Grasse in 1732, Fragonard moved with his family to Paris when he was still a young boy, and in his late teens he studied with two lions of 18th-century French painting, Jean Siméon Chardin and François Boucher. After winning the illustrious Prix de Rome in 1752, he entered the École royale des élèves protégés. Fragonard went to Rome in 1756 and stayed in Italy for five years, traveling the country, copying paintings, and working with fellow French artist Hubert Robert. He returned to Paris and based on the strength of his painting of an ancient Greek tale, he was approved by the Académie royale in 1765. Almost overnight, he came to embody the hopes of the French school and seemed poised to resurrect the fortunes of history painting, the most prestigious painting category.

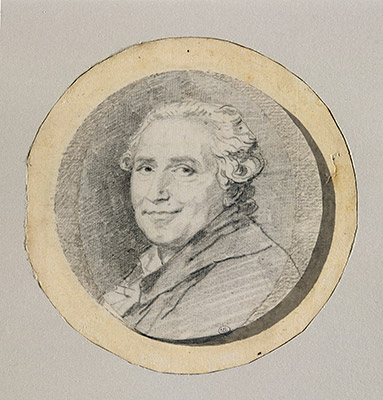

Jean Honoré Fragonard

Self-Portrait, Three-Quarters to the Left, c. 1778–1780

black chalk

13 x 10.2 cm

Musée du Louvre, Paris, RF 41191

© RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY, Photo: Gerard Blot

Jean Honoré Fragonard, The Swing, c. 1775/1780, oil on canvas, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.17

Soon, however, Fragonard largely dropped out of the rigid official system that governed artists’ professional development and, to the disdain of his contemporaries, chose to work for an eager and growing market of wealthy private collectors. Freed from thematic and formal constraints, he concentrated on freely brushed small works and decorative paintings that he often infused with latent (or in some cases more explicit) eroticism. With his extraordinary imagination and artistic virtuosity, Fragonard was almost unequaled in his ability to challenge the traditions of painting and the conventions of aesthetic taste.

In the aftermath of the French Revolution, Fragonard became an important arts official and helped establish new museums at the Palais du Louvre and at Versailles. Yet by the time of his death in 1806, he had faded into obscurity, and it was not until the 1840s that his stylistic freedom—characterized by bravura brushwork and brilliant coloring—came to be seen as a singularly important precursor to Romanticism.

More Images of Women Reading

in the National Gallery of Art Collection