Venus with a Mirror was certainly one of Titian’s most popular compositions. Some 15 copies and variants are known, made by the master or his assistants. This canvas, though, is by Titian’s hand alone and must have been the first of all the copies to be painted. It remained in the artist’s studio until his death, more than 20 years after he painted it.

During the Renaissance the very idea of love was allied with the contemplation of beauty, and the imagery of mirror and reflection was often found in love poetry. In Italy, the theme goes back to Petrarch’s complaint to the mirror, il mio adversario (my rival), which held the face of his beloved Laura. Many artists painted Venus—or their own mortal lovers—admiring a mirrored reflection.

Why do we think this was the original Venus with a Mirror?

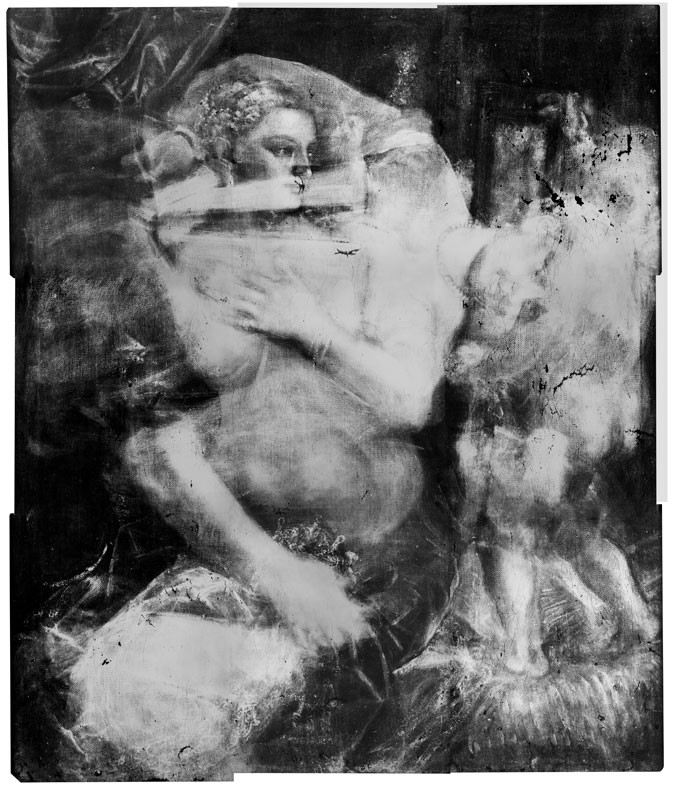

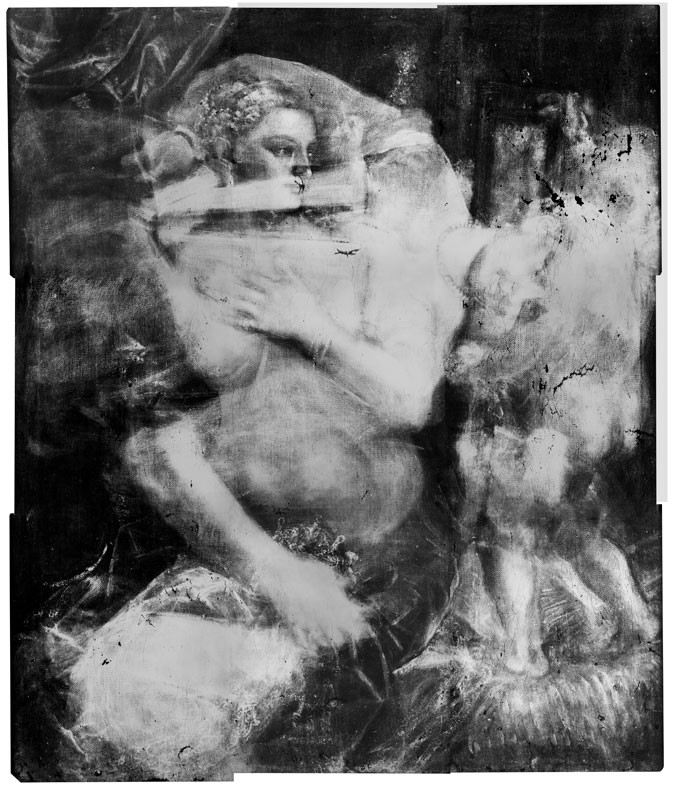

Other than the fact that this was the version of the painting Titian chose to keep for himself, strong evidence comes from x-ray analysis. The canvas was rotated and reused. The original horizontal image (the canvas rotated here to show the original painting in its correct orientation) depicted a man and a woman in three-quarter-length standing side by side. The lush velvet drapery that now covers Venus’ lap was originally the man’s cloak—it was left untouched when Titian repainted the rest of the canvas. Such clever reuse is a measure of Titian’s inventive genius and could only occur as he was first creating the new composition.

See Other Paintings of Venus With a Mirror

But does the shining eye caught in the mirror of Titian’s goddess really look back at itself? It is a bit ambiguous: perhaps instead she has been distracted from her own reflected loveliness, her attention drawn to something or someone outside the frame. It is tempting to understand that person as the artist working in her presence. If Titian “pictured” himself in the composition as the envious lover, it would help explain his long attachment to the work. Of course, Titian was also a busy and astutely businesslike artist and may simply have kept it as a model for copies.

Two cupids attend Venus. One holds the mirror as the other reaches to crown her with a garland. She adheres closely to the canon of female beauty extolled by Renaissance poets: blond hair, fair skin flushed with pink, red lips and arched brows. For Venus’ pose, Titian ingeniously transformed a well-known ancient statue in the Medici collection, yet this Venus has no trace of marble’s coolness. It vividly conveys the warmth and glow of yielding flesh, the richness of velvet, and the glint of gold embroidery. We sense as much as see the softness of the fur-lined robe as it brushes against her skin and the smooth perfection of her rose-tinted cheek. A cupid’s wing shimmers with iridescence.

It is the mastery—and the variety—of Titian’s brush that captures this wealth of textures. In Venus’ face small strokes are blended to reproduce her ideal complexion, and a careful line traces brows. But as she draws an arm across her breast, contours are softened to suggest a pliant body giving way under touch. A deep layering of translucent red glazes—unreadable up close—resolves into the folds of dense velvet at a greater distance. In the border, an intricate embroidered pattern is conjured by quick flashes of yellow and white highlights.