Introduction

David Seymour (1911–1956), known as Chim (pronounced shim) after his original Polish surname, was a pioneering photojournalist whose unapologetically compassionate work reflected both his deep-seated humanism and his belief in the unique ability of photography to awaken the public’s conscience. Highly cultured and conversant in eight languages, Seymour combined technical skill, formidable intellect, and intense empathy to tell stories photographically.

Chim at work, photographer and date unknown, © Chim Archive

Constantly on the move, Seymour used his camera as a weapon with which to document—and to combat—the injustice, unrest, and violence that plagued Europe, and later the Middle East, from the mid-1930s through the mid-1950s. He took notable battle photographs during the Spanish Civil War and covered the Suez Crisis in 1956, but his most memorable photographs document civilians behind the front lines coping with the devastating effects of war. In these deeply affecting images, Seymour captured singular historical moments while simultaneously evoking universal human themes.

Seymour was also an accomplished portraitist—of intellectuals and, later in his career, celebrities—and an avid documenter of street life. One of his greatest legacies is the storied Magnum Photos cooperative, which he cofounded in 1947 and directed for two years after his close friend Robert Capa’s untimely death in 1954.

Biography

Chim’s 1936 press card from the French photo agency RAP, which was owned by a family friend, © Chim Archive

Born Dawid Szymin in Warsaw, David Seymour grew up in a cosmopolitan household. His father was a leading publisher of Hebrew and Yiddish books, and he ran a bookstore that was a locus of Warsaw’s Jewish intellectual life. During World War I (1914–1918) the family fled to Minsk and then Odessa before returning to Warsaw in 1919.

A passionate reader, talented pianist, and precocious linguist, Seymour passed his baccalaureate in 1929 and then studied printing technology at Leipzig’s prestigious Staatliche Akademie für Graphische Künste und Buchgewerbe. He returned home after graduating in 1931, but faced with Poland’s worsening economic and political climate, he decided to continue his education in Paris. He enrolled at the Sorbonne in 1932 to study physics and chemistry.

Concerned about straining his family’s resources, Seymour in 1933 sought work from David Rappaport, a family friend who ran a Paris-based photo agency. Though untrained in photography, Seymour was a quick learner. His photographs, largely of working-class subjects, soon began appearing in several Parisian illustrated periodicals. He started stamping his prints “Chim,” an abbreviated version of Szymin that was easier to pronounce. In 1934, he was appointed staff photographer for Regards, a leftist illustrated weekly that pioneered humanist photography in France. During these early years in Paris he also forged a lifelong friendship with Robert Capa and

Regards sent Chim to report on the Spanish Civil War soon after its outbreak in July 1936. His photographs of battles and especially of life behind the lines cemented his reputation as a leading photojournalist. He photographed the defeated Republicans fleeing to France and then covered the voyage of the first ship to carry Spanish émigrés to Mexico.

Seymour made his way from Mexico to New York, arriving just after the beginning of World War II. Taking advantage of immigration regulations that allowed foreigners to open businesses, he teamed up with German photographer Leo Cohn to open what soon became a highly regarded photo-finishing business (called Leco) in New York. Many notable photographers who had left Europe, including

A wartime holiday card from the photo-finishing firm Leco depicts Chim as a soldier, December 1944, © Chim Archive

Chim was drafted in 1942. While training in military intelligence at Camp Ritchie, Maryland, he became a naturalized U.S. citizen. Fearful of reprisals by the Nazis against his family in occupied Poland, he adopted a new, Anglo-Saxon name, David Robert Seymour. Between 1942 and 1945, Chim served in photo reconnaissance and interpretation in the U.S. Army. He worked in England, France, and eventually occupied Germany, earning several promotions and a bronze star. While in Paris to celebrate the city’s liberation he found that his old apartment had been sealed by the SS, but that nothing had been removed. Soon he would learn that both his parents had been killed by the Nazis.

In 1947, Seymour cofounded Magnum Photos and served as its first vice president. In 1948, he was commissioned by UNICEF to photograph the plight of Europe’s children in the aftermath of World War II. The resulting images—striking and sympathetic—are among his best-known works and cemented his reputation.

In the 1950s, Seymour made Rome his home base. He became the trusted portraitist of many film stars—including Sophia Loren, Gina Lollobrigida, and Ingrid Bergman—whose images were in high demand by magazines such as Life. With a deep affinity for Mediterranean culture, he traveled frequently around Italy and Greece to pursue his own photography. He also became a dedicated documenter of the new state of Israel, with which he identified closely.

He continued to photograph regularly, even after assuming the presidency of Magnum following Capa’s death in 1954. Seymour remained president until November 10, 1956, when he and French photographer Jean Roy were killed by Egyptian machine-gun fire en route to covering a prisoner exchange in the aftermath of the Suez Crisis.

Funeral services for Chim and Paris Match photographer Jean Roy, November 14, 1956, near Port Fuad, Egypt, photographer unknown, © Chim Archive

Chim at Work

Chim was especially adept at composing powerful images, even of fleeting events. Whenever possible, he carefully prepared to cover a story; he learned all he could about the issue or subject and thought about the story both conceptually and pictorially, leaving as little to chance as possible, as though he imagined photographs in his mind before actually taking them.

Well-versed in math, science, and modern printing technology, Seymour quickly mastered the medium’s technical aspects. In addition to his instinct for composition he was particularly attentive to lighting and depth of field. Many of his images are sharp from the immediate foreground to the distant background, providing a plethora of information and indicating the context for a scene. Seymour often incorporated signs, banners, or posters into his images that functioned like

Nearly all of Seymour’s photographs focus on people. Occasionally a subject will look directly into the lens, but more often Chim preferred to shoot people absorbed in what they were doing. The sympathy and authenticity that radiate from his most arresting photographs derive from his up-front working method. Rather than trying to be invisible, he engaged with his subjects and gently earned their trust, which in turn encouraged them to act naturally around the camera. Seymour saw his work as a collaborative effort between himself and his subject.

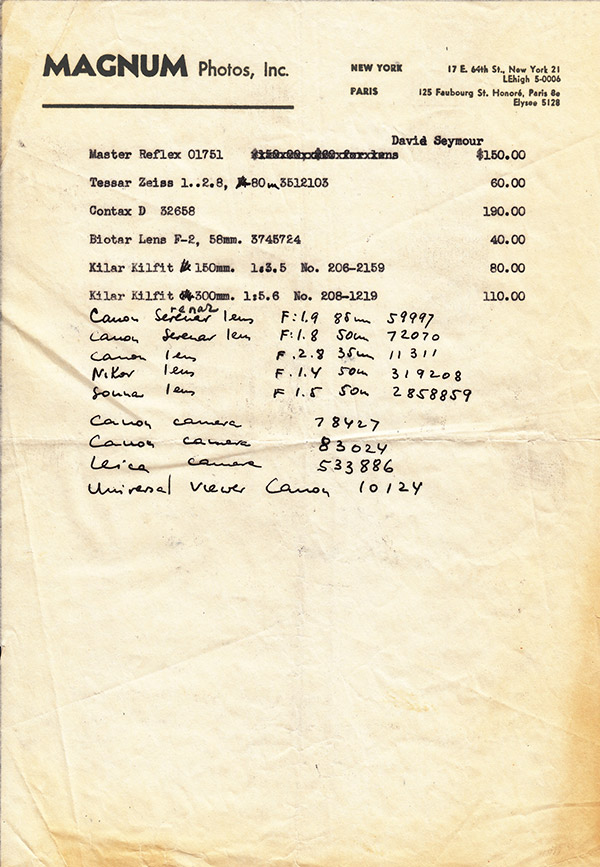

He favored two camera models, Leica and Rolleiflex. The revolutionary Leica was small and unobtrusive, perfect for working quickly; the Leica proved that the small negatives (24 × 36 mm) produced with 35 mm film could be used professionally. He opted for the more deliberate Rolleiflex—a twin-lens reflex camera that produced remarkably sharp, large, square-format negatives (6 × 6 cm)—when he had more time to compose his images (such as in his series on children in post–World War II Europe). Seymour was well known for his expertise in developing and printing and also for his excellent eye in laying out a photo story.

A list of Chim’s photo equipment, c. 1953, © Chim Archive

Paris

Seymour arrived in Paris from his native Poland in 1932. While studying science at the Sorbonne, he found work at a family friend’s small photo agency. Though he had no formal photographic training, he had likely been exposed to modern photography and graphic arts during his studies in Leipzig, and using a borrowed camera, he was soon making publishable photographs.

Seymour quickly adapted to life in Paris. He wrote to his girlfriend in Warsaw in 1933, “I am sitting at my big desk, with a globe of the world on it, in my new apartment….I am getting to know Paris. I am becoming a part of it….I am a reporter, or more exactly, a photo-reporter.” He drifted away from the Polish community and picked up new photographer friends, especially

Chim arrived in Paris amid heightened domestic and international tension. France was bitterly divided politically and Hitler had recently assumed Germany’s chancellorship. But this also proved a propitious moment to enter photojournalism. Innovative illustrated weeklies proliferated in Paris in the early and mid-1930s, and they required large numbers of topical pictures.

Regards, the pioneering weekly picture magazine for which Chim began to work in 1934, was perfectly in tune with his progressive political outlook. Run by leftist intellectuals, Regards championed the cause of the Front Populaire, a clamorous political alliance of trade unionists, socialists, and communists that won the general election in May 1936.

A flyer for a 1933 Paris photo exhibition includes Chim, only a year into his career, among an impressive roster of photographers, © Chim Archive

Henri Barbusse and Left-wing Intellectuals at his Monde Office, Paris

David Seymour (Chim), Henri Barbusse and Left-wing Intellectuals at his Monde Office, Paris, 1935, printed 1982, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.38.1

Acclaimed French writer Henri Barbusse, a long-time pacifist and communist, was a leading figure in the campaign of French leftist intellectuals to combat fascism and improve workers’ conditions. Chim took this group portrait of Barbusse (in the front row, third from left) and his like-minded peers in the Paris offices of Barbusse’s new literary journal, Monde, during the International Writers’ Congress for the Defense of Culture. By posing them before a socialist realist mural and practically incorporating some of the painted figures into the portrait, Chim underscored the close alliance of intellectuals and workers that would be critical to electing the leftist Front Populaire to office in France in 1936.

Romain Rolland

David Seymour (Chim), Romain Rolland, 1935–1936, printed before 1962, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.22

Like Barbusse, Romain Rolland was an acclaimed writer, pacifist, and antifascist. Winner of the 1915 Nobel Prize for literature and a regular correspondent with the likes of Mahatma Gandhi and Sigmund Freud, Rolland was a towering intellectual figure whom many saw as the symbolic grandfather of the Front Populaire.

Chim made this portrait of the distinguished writer, nearing age seventy, on the balcony of his childhood home in Burgundy. The unusual composition—closely cropped, off-center, and shot from above—suggests Rolland’s intellectual restlessness, an effect echoed by the author’s piercing eyes and serious mien.

Anti-War Rally, Saint-Cloud

David Seymour (Chim), Anti-War Rally, Saint-Cloud, 1936, printed 1982, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.38.3

Chim quickly became adept at shooting the mass demonstrations that were a signal feature of French politics in the Front Populaire era. He made this photograph at an antiwar rally in Saint-Cloud, just outside Paris, in August 1936—an event that assumed special urgency in the aftermath of Hitler’s reoccupation of the Rhineland in March and the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in July.

Chim here captured in one shot individual marchers, the sense of the emotionally charged crowd, and by framing the scene against the giant disarmament posters, the rationale for the demonstration. The composition gains much of its potency from its clever rhyming of the marchers’ peacefully pumping fists with the static, bellicose hand clenching a sword in the English-language “War Is Insanity” poster (at top right).

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War began in July 1936. The officer corps, led by General Francisco Franco, attempted to overthrow the Frente Popular, a leftist coalition that had narrowly won recent elections. The conflict quickly assumed an international dimension: Franco’s Nationalist forces were backed by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, while the poorly trained and equipped Republicans received support from the Soviet Union and an international brigade of sympathizers who hoped to save the elected government.

War photography dates to the Crimean War (1853–1856), but the Spanish Civil War was the first conflict to be extensively photographed for a mass audience. It marks the birth of modern war photography. A corps of professional photographers equipped with small cameras was able to take pictures of all aspects of the war, including close-ups of battles, and their work was published almost immediately in newspapers and magazines across the world.

Chim, sent by Regards, was one of the first photographers on the scene, and he spent much of the next thirty months shooting the war. He covered the Republicans’ earliest battles but soon turned his focus to the plight of civilians behind the front lines and the wider effort to support the government forces.

Letter from the Paris office of the International Committee of Coordination and Information for Assistance to Republican Spain asking Chim quickly to send two of his photos of Republican leaders to Amsterdam for an exhibition, © Chim Archive

Republican Soldiers in Combat, Spanish Civil War

David Seymour (Chim), Republican Soldiers in Combat, Spanish Civil War, 1936, printed before 1962, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.20

Chim was not eager to cover battles, but he did so when circumstances demanded. This was especially the case before the arrival in Spain of two of Chim’s fellow Regards photographers who would quickly prove inveterate battle photographers: Capa, one of his closest friends, and Capa’s companion, Gerda Taro, who would be killed while covering the war in 1937.

In this stunningly composed image, Chim perfectly aligned his lens with the wheel of an artillery cannon that has just been fired (as evidenced by the smoke pouring forth from the muzzle). To do so, he had to be in an exposed position on top of the ridge behind which the Republican riflemen take cover. The blurred figures and billowing smoke convey the tumult of battle even as the cloudless sky and rolling hills evoke a larger, timeless landscape.

The Ernst Thaelmann Brigade

David Seymour (Chim), The Ernst Thaelmann Brigade, 1936, printed 1982, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.38.4

More than 30,000 foreign volunteers—chiefly French, German, Italian, and American—rallied to take up arms on the Republic’s behalf. The foreign units were eventually organized into five international brigades, the first army of its kind in modern history.

This photograph depicts the Ernst Thaelmann Battalion, a German unit named for a leading communist who had been imprisoned by the Nazis. It quickly gained a reputation for being one of the bravest and best-trained units in the international brigades.

Like the photograph of the Saint-Cloud peace rally, this image highlights Chim’s ability to encapsulate narrative in a single frame. The fresh-faced soldier in the center conveys the spirit of idealism and determination that suffused the international volunteers, while the line of identically posed and uniformed soldiers ranged behind him suggests the vast numbers of like-minded fighters. The battalion’s flag, meanwhile, featuring a hammer and sickle and the name of the unit, plainly identifies the scene, functioning like an internal caption.

Pablo Picasso in front of Guernica, Paris

David Seymour (Chim), Pablo Picasso in front of Guernica, Paris, 1937, printed 1982, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.38.2

In late May 1937, during a brief hiatus from his war coverage, Chim collaborated with Henri Cartier-Bresson on an issue of Regards dedicated to the Paris World’s Fair. Chim made this well-known portrait of

Picasso’s searing anti-Franco masterwork was motivated by the Nazi air force’s merciless pummeling of the Basque town of Guernica on April 26. Over the course of three hours, German planes dropped an unprecedented 100,000 pounds of high explosive and incendiary bombs that leveled the historic town and caused 1,600 civilian casualties. The usually apolitical Picasso made no bones about what lay behind his work during this period: “I am expressing my horror of the military caste which is now plunging Spain into an ocean of misery and death.”

Chim’s portrait depicts Picasso as both an artist and a Republican partisan. The composition projects Picasso into the painting and suggests the artist’s identification with the immense, horror-stricken figure above him. Picasso’s crossed arms underscore his defiance, as does the ominous shadow that falls across half his face.

National Lottery, Barcelona, Spanish Civil War

David Seymour (Chim), National Lottery, Barcelona, Spanish Civil War, 1938, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.33

Since its inception in 1812, the national lottery has been both an integral element of Spanish culture and an important source of government revenue. Recognizing this, the Republicans and Nationalists each launched their own lotteries during the Spanish Civil War. Here, a Republican lottery vendor in Barcelona sits in his adult tricycle festooned with tickets.

Chim’s photograph captures the bizarre combination of continuity and rupture that often characterizes a home front during war. Here, the only obvious sign that this was taken during wartime is the giant poster in the background, which translates as “There is no greater honor for the country than to defend it.”

This photograph, slightly cropped, appeared in a mammoth 24-photograph essay by Chim, entitled “Barcelona, A City at War,” that ran in Life magazine on November 28, 1938. Chim’s photographs, the accompanying text said, “show how a people learn to live with war.”

The Exodus from Spain into France of the Defeated Loyalists at the End of the Civil War

David Seymour (Chim), The Exodus from Spain into France of the Defeated Loyalists at the End of the Civil War, 1939, printed 1982, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.38.12

With Franco’s victory all but inevitable by the end of 1938, nearly half a million Republican soldiers and citizens made their way through the wintry Pyrenees to the French border. Chim accompanied the refugees through the pass at Le Perthus and took this photograph there in February 1939 as men from the Republican Army—whom the French stripped of their weapons—waited to enter France.

Spanish Refugees Preparing to Board S.S. Sinaia

David Seymour (Chim), Spanish Refugees Preparing to Board S.S. Sinaia, 1939, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.29

Spanish Refugees aboard S.S. Sinaia

David Seymour (Chim), Spanish Refugees aboard S.S. Sinaia, 1939, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.32

The French were unprepared for the massive influx of Spanish refugees and moved them into improvised camps set up along Mediterranean beaches. The Republican government, now in exile, tried to arrange for the passage of many of the refugees to Mexico and South America. The new French weekly Match assigned Chim and writer George Soria (with whom Chim collaborated frequently for Regards) to cover the May 1939 voyage of the S.S. Sinaia, the first ship to carry refugees to Mexico.

The Sinaia’s sailing was a logistical challenge that required the cooperation of English, French, Mexican, and Spanish authorities. For some, making it onto the ship was more trying than the 23-day journey itself. One passenger described the “hair-raising” four-day process of collecting the refugees and transferring them to the boat as “more emotionally exhausting than anything I have ever experienced.”

Chim’s photograph of the people on the quay captures the chaos that preceded the departure. That of the men sleeping on deck highlights the ship’s overcrowded conditions but also encapsulates the refugees’ utter exhaustion after years of war, escape to France, and months spent in a makeshift refugee camp. Several of Chim’s Sinaia photos were published in the United States by Life.

Children of Europe

Chim did not work as a photojournalist during World War II. He ran a photo-finishing business in New York and then served as a photo-interpreter with the U.S. Army in Europe from 1942 to 1945. In 1947 Chim, Capa, and Cartier-Bresson fulfilled their long-held desire to form a new kind of picture agency. Together with English photographer George Rodger, they founded Magnum Photos, an international photographic cooperative with editorial independence.

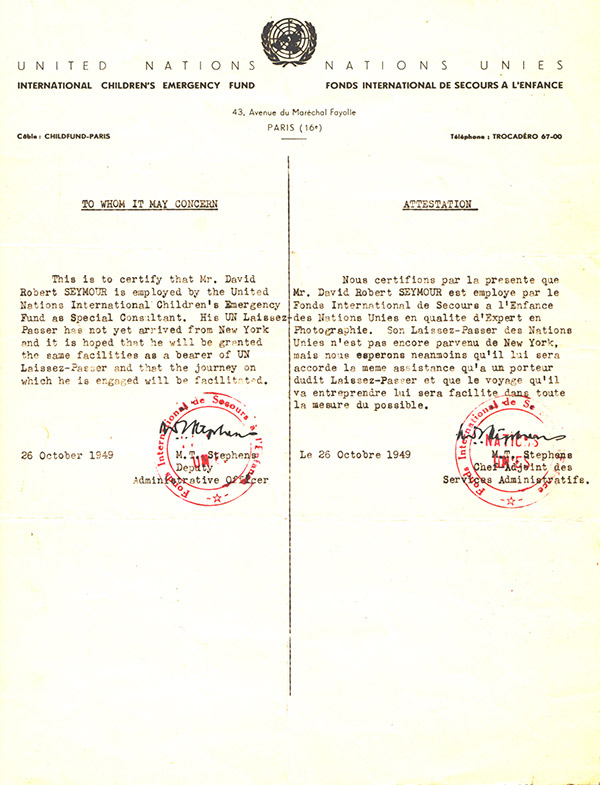

In 1948 Chim accepted an assignment to take photographs for a UNICEF book intended to show the horrid conditions endured by needy children in postwar Europe and the work undertaken by the United Nations agency to ameliorate their situation. For Chim it was a perfect project. He had always liked being around children and loved to photograph them. As a staunch pacifist, he knew that nothing could speak more poignantly to the senseless destruction of war than the plight of these innocent victims.

In twelve weeks Chim traveled to his native Poland and to Hungary, Austria, Italy, and Greece. No other series better demonstrates his deeply ingrained humanitarian sympathies, and the profoundly moving photographs are widely considered to be among his best work. Forty-seven of the approximately 5,000 photographs that Chim took appear in the UNICEF book Children of Europe (1949). Select images also were published in leading magazines throughout the world, including eleven in Life’s 1948 Christmas issue.

A letter from UNICEF certifying that Chim is employed as a special consultant, October 26, 1949, © Chim Archive

Terezka, A Disturbed Child in a Warsaw Orphanage

David Seymour (Chim), Terezka, A Disturbed Child in a Warsaw Orphanage, 1948, printed 1982, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.38.5

Terezka grew up in a German concentration camp. Chim photographed her at a home for mentally disturbed children in Warsaw. When asked to draw a picture of “home,” she managed only the chaotic scribbles visible on the blackboard. Though she pauses to look at the camera, her wild-eyed stare suggests her mind, at least, is still in a darker place.

During this trip to Poland, Chim learned the details of his parents’ deaths during the war. They were killed in 1942 in a ghetto created by the Nazis in Otwock, a resort town just outside Warsaw where the Szymin family formerly had a summer house. It is not difficult to imagine that Chim—visiting his devastated hometown for the first time since the war’s end—regarded Terezka with sympathy.

Albergo dei Poveri, Naples

David Seymour (Chim), Albergo dei Poveri, Naples, 1949, printed 1982, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.38.6

Naples’ Albergo dei Poveri was a massive royal alms house constructed in the eighteenth century to shelter, nourish, and provide work to destitute Neapolitans. After the war, vagrant children were remanded by the juvenile court to the Albergo, where they went to school and learned trades.

The intimacy of many of Chim’s photographs of children derives in part, as here, from being taken at the children’s height. This frame-filling image manages both to offer a close-up portrait of the boys in the foreground and to suggest the countless number of children affected by the war. It was printed across two pages in the centerfold of the UNICEF book.

Child’s Funeral, Matera, Italy

David Seymour (Chim), Child’s Funeral, Matera, Italy, 1948, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.30

Chim made this bird’s-eye-view photograph of a funeral procession for a child in Matera, an ancient hillside town in a region of southern Italy that was among the most impoverished in Europe. (In Italy, a child’s hearse is traditionally white.) Chim’s trip to Matera may have been instigated by his close friend Carlo Levi, a writer and painter from northern Italy whose shocking description of the town’s dire conditions, published in Christ Stopped at Eboli (1945), drew national attention.

Besides its devastating poverty, the town’s deep ties to Catholicism also likely drew Chim’s attention. Despite being Jewish and agnostic, Chim had an abiding interest in Catholic rites and festivals, which would culminate in his making photographs for a book on the Vatican in 1949.

Delinquency, Budapest, Hungary

David Seymour (Chim), Delinquency, Budapest, Hungary, 1948, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.4

Policewomen patrolling a black market in the center of Budapest question a shoeless boy tinkering with spare automotive parts. The caption on the reverse of the photograph says the policewomen are trying to learn “whether he needs proper care and attention.”

Improvised Chemistry Lab Experiment, Szeged, Hungary

David Seymour (Chim), Improvised Chemistry Lab Experiment, Szeged, Hungary, 1948, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.3

Beyond the children’s immediate material needs, UNICEF also sought to redress the educational gap that resulted from many children being unable to attend school during the war. Chim’s wonderfully composed photograph of two female Hungarian students huddled over a chemistry experiment in a seemingly “normal” school setting captured the hope that a new generation would soon be able to assume its place in European society. At the same time, the improvised lab materials—with light bulbs serving as beakers—called attention to the schools’ need for new equipment.

David Seymour (Chim), Improvised Chemistry Lab Experiment, Szeged, Hungary (Verso), 1948, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.3

Because they were often reproduced in books or magazines, the reverses (or versos) of Seymour’s vintage prints bear stamps, handwritten notations and measurements, and occasionally, as here, lengthy captions. This photograph includes both the Magnum Photos stamp crediting Seymour and a “special photo for UNESCO” stamp because it is from Chim’s UNICEF assignment. The captions were often written by photo editors, but it is tempting to speculate that Chim, who studied advanced chemistry before taking up photography, might have been especially interested in detailing this experiment.

Elections at Children’s Town, Hajduhadhaza, Hungary

David Seymour (Chim), Elections at Children's Town, Hajduhadhaza, Hungary, 1948, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.2

Several European municipalities established children’s communities to care for parentless youth after the war. The children’s villages, sometimes located in abandoned barracks, aimed to provide more extensive education and training than standard orphanages. One distinguishing characteristic of the villages was “self-government,” which was intended to impart a sense of responsibility and community.

Chim took this photograph of a boy using a friend’s back for support as he fills out a secret electoral ballot at the children’s town in Hajduhadhaza, Hungary. Here, children older than age ten elected a mayor, police captain, postman, and members of a “children’s court” that settled disputes. Chim’s intimate image is full of hope: despite years of tragic hardship, the children are seen to be eager, cooperative participants in a model civil society.

Tailoring Workshop at Children’s Town, Hajduhadhaza, Hungary

David Seymour (Chim), Tailoring Workshop at Children's Town, Hajduhadhaza, Hungary, 1948, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.1

Chim’s skillful manipulation of light and shadow adds poignancy to this quiet photograph of an instructor mentoring a student at the tailoring shop in Hajduhadhaza’s children’s town. The hopeful image underscores the potential for a return to normalcy via the age-old process of passing knowledge from one generation to the next.

Italy

Chim’s 1956 journalist pass from Italy’s State Railways, © Chim Archive

From 1949, Chim started spending more time in Italy. Though he still traveled constantly and was frequently in Paris to attend to Magnum business, Rome became his de facto home base until his death.

Chim’s friends recognized that while he was always generous and good-humored, he was also deeply sad—especially in the aftermath of the war and the Holocaust. As Henri Cartier-Bresson described it, Chim “carried the weight of the world on his shoulders.”

Italy, however, offered Chim a welcome escape. He was drawn to the comforting continuity of Italy’s customs and traditions, particularly those related to Roman Catholicism, and to the renewed optimism of the 1950s, when Italy became a haven for celebrities. A famous gourmet and an impeccable dresser, Chim especially appreciated Rome’s fine restaurants and skilled clothes makers. As John Morris, executive editor of Magnum Photos, later recalled, “Chim’s greatest days were in Rome. He owned that town.”

French Croix de Bois Choir Members at a Papal Mass

David Seymour (Chim), French Croix de Bois Choir Members at a Papal Mass, 1949, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.15

Chim, though not a believer, had a deep interest in religion, religious institutions, and in the fulfillment people found in passionate belief. This fascination increased after the war, and in 1949 Chim agreed to take photographs for a book that Ann Carnahan planned to write on the Vatican (The Vatican: Behind the Scenes in the Holy City, 1949).

The two worked together in Vatican City for ten weeks, from the time the gates opened in the morning until they were closed in the evening. Seymour took some 2,500 photographs, including a portrait of the pope made during a private audience. His friends started calling Seymour “Il Papavile” because he became so steeped in the pomp and ceremony of the Catholic Church.

In this image, Chim photographs the photographers. He captures the French choir members’ excitement at being near the pope and slyly comments on photography’s ubiquitous role in society.

The Great Day of Gubbio, the Festa of the Ceri

David Seymour (Chim), The Great Day of Gubbio, the Festa of the Ceri, c. 1951, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.9

On his own, Chim began a project to document Italy’s great religious festivals. He was especially interested in those that had long histories, pageantry, and fervor. In the early 1950s he attended Gubbio’s famed Corsa dei Ceri (the race of the candles)—an annual civic and religious celebration that likely dates to the twelfth century.

On the morning of May 15, each of three colorfully attired teams parades through the city with a “candle,” a half-ton wooden pillar topped with a statue of a saint. In the evening, the three teams race up a steep hillside to reach the church atop the city where the ceri reside the rest of the year.

Chim, his camera always at the ready, here captures an unusual event: one of the ceri has toppled, and its bearers, joined by spectators, are trying to right it. The caption on the reverse reads, “When a Ceri tips over it is considered a great shame for the confraternity carrying it, and for months after the talk goes on in the cafes of Gubbio about it.”

Religious Festival, Italy

David Seymour (Chim), Religious Festival, Italy, c. 1951, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.7

This image of religious absorption is particularly arresting because the young man’s robes, the banner he holds, and the architectural setting suggest a direct link to impassioned religious practice from centuries earlier.

Sunday Afternoon, Baldo Plays Morra

David Seymour (Chim), Sunday Afternoon, Baldo Plays Morra, 1951, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.28

Chim was always drawn to street life, especially customs and traditions that gave a unique flavor to human interaction in different regions and countries. In this image, he captures a group of young men in Gubbio playing morra, a hand game (similar to “odds and evens” or “rock-paper-scissors”) that entails guessing the total number of fingers stretched out simultaneously by two opponents.

Venice Fish Market at the Rialto

David Seymour (Chim), Venice Fish Market at the Rialto, 1950, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.16

David Seymour (Chim), Venice Fish Market at the Rialto, 1950, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.17

David Seymour (Chim), Venice Fish Market at the Rialto, 1950, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.18

At Venice’s famed Rialto fish market, Chim captured the intimate and seemingly mysterious process by which fishmongers auctioned fish by the lot to dealers. After the fishmonger-cum-auctioneer announced that a lot was open for bidding, dealers would approach him individually and whisper offers in his ear. The strangely silent proceedings continued until all the interested dealers had whispered their bids, at which point the auctioneer would announce the winner.

Truman Capote

David Seymour (Chim), Truman Capote, 1953, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.21

Italy in the 1950s became an important center of movie making, and American magazines, such as Life and Look, increasingly devoted coverage to movie stars. Chim, low-key and personable, made celebrities and would-be celebrities feel comfortable. He quickly became the favored photographer of Ingrid Bergman, whom he shot on many occasions. He produced several widely published stories on a new star, Gina Lollobrigida (including covers for both Life and Look), and soon he was asked to publicize other up-and-comers, including Joan Collins, Ava Gardner, and Audrey Hepburn.

In 1953 the magazine Picture Post commissioned Magnum Photos to document the shooting of Beat the Devil. The movie had the makings of a blockbuster. Set on Italy’s dramatic Amalfi coast, it was directed by John Huston, had a screenplay written by Truman Capote, and featured an all-star cast, including Humphrey Bogart, Gina Lollobrigida, Peter Lorre, and Robert Morley. In the end, however, it was a critical and financial flop.

Chim filled in on the assignment for Capa, whose passport had been temporarily confiscated by U.S. authorities after Capa had been accused of being a communist. This image shows Truman Capote and Robert Morley relaxing aboard a ship off the Italian coast.

Arturo Toscanini in His Home, Milan

David Seymour (Chim), Arturo Toscanini in His Home, Milan, 1954, printed 1982, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.38.7

Arturo Toscanini did not like to be photographed, but his daughter, with her father’s consent, invited Chim to their home in Milan to photograph the 87-year-old maestro in the year he retired as music director of the immensely popular NBC Symphony Orchestra. It was a treat for Chim, an aficionado of classical music who, before changing paths in his student days, had first studied to be a concert pianist.

This moving portrait juxtaposes the vigorous but aged conductor seated at the keyboard with the haunting death masks of three of his inspirations: Beethoven (mostly obscured), Verdi, and Wagner. Toscanini would be the first subject in a series of Chim’s portraits of aged men who in their life’s work had raised the spirit of humankind.

Bernard Berenson at Ninety, Visiting the Borghese Gallery, Rome

David Seymour (Chim), Bernard Berenson at Ninety, Visiting the Borghese Gallery, Rome, 1955, printed 1982, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.38.8

Chim’s portrait of 90-year-old Bernard Berenson, the renowned art historian, complements his portrait of Toscanini taken the year before. Both men were towering cultural figures with close ties to Italy who had dedicated their careers to the arts, and both were in the twilight of their lives.

Chim photographed Berenson as he revisited several of his favorite works of art at Roman museums, including, here,

Israel

A page from Chim’s passport that includes, at right, the entry visa for his first trip to Israel, October 12, 1951, © Chim Archive

From his base in Rome, Chim turned his attention increasingly toward the Mediterranean. He often traveled to Greece, and beginning in 1951 he visited Israel almost yearly to document the emergence of the new Jewish state, which had been established in 1948.

Chim’s attraction to Israel was almost instinctive. The culture that he had grown up with in Poland was destroyed during World War II. His parents, relatives, and friends had been killed or had fled. In fact, the inveterate traveler did not return to Eastern Europe at all after 1948.

Israel, by contrast, offered hope. As Seymour wrote his sister, “It was like coming home again. It was like picking up the living threads of my life, for which I had been searching in vain on the heaps of rubble and ash in the ruins of Warsaw.” Israel in many ways embodied Chim’s idea of a political utopia, fusing communal living, a melding of nationalities, pioneering spirit, and fervent idealism.

The First Child Born in the Italian Immigrant Settlement of Alma, Israel

David Seymour (Chim), The First Child Born in the Italian Immigrant Settlement of Alma, Israel, 1951, printed 1982, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.38.9

Chim’s photograph of a beaming Eliezer Tritto holding up his newborn daughter—the first child born at the Italian immigrant settlement of Alma—captures the determination and idealism of the émigrés who helped establish the new state.

Chim was attracted to the settlement because of its residents’ unusual background. They hailed from San Nicandro, a small, impoverished town in southern Italy, and in the 1930s had converted to a homegrown version of Judaism under the sway of a cobbler and mystic who had grown disenchanted with Catholicism. The San Nicandro Jews were officially received into the Jewish community in 1946. Sixty or so emigrated to Israel in 1949, where they joined Holocaust survivors and Jews who had been persecuted in other countries.

Chim’s photo conveys the settlers’ resolve to make the state viable—both through human reproduction and through the cultivation of the hardscrabble land from which sprout tiny, new whitewashed homes. The baby’s white baptismal robe visually echoes the houses and speaks to the community’s Italian roots.

Israel Wedding

David Seymour (Chim), Israel Wedding, 1952, printed before 1962, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.5

Chim was fascinated with the pioneering spirit and sheer vitality that infused the settlers. Here he photographed a Jewish wedding in a barren border region. The young couple stands beneath a huppah, a traditional wedding tent, on which the Star of David can be glimpsed. In lieu of tent poles, however, the improvised tent is held aloft by a pitchfork and a rifle, tools—Chim quickly realized—that were emblematic of the country’s struggle for survival and prosperity.

Funeral on Israeli Border

David Seymour (Chim), Funeral on Israeli Border, 1953, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.26

The omnipresent threat of violence was the grim counterpoint to the heady idealism that animated Israel’s new settlers. In December 1953, Chim photographed the funeral of a young Israeli soldier who had been killed while standing guard near the border. Here two men carry the body, wrapped in a Jewish prayer shawl, as a rabbi recites a prayer.

Suez Crisis

Chim’s reportage on the 1956 Suez Crisis for Newsweek was his last. The crisis was triggered by Egypt’s nationalization of the Suez Canal. In response, France and Britain supported an Israeli invasion of the Sinai, launched on October 29, and soon injected their own forces to secure the canal.

Chim had been in Greece when the conflict broke out. Though he had not been a war correspondent since his time in Spain, he was determined to get to Egypt to cover the hostilities. Friends tried to dissuade him, but Chim argued that Magnum had to cover world events and that he was the only Magnum photographer available. His close emotional ties to Israel probably also impelled him to take part.

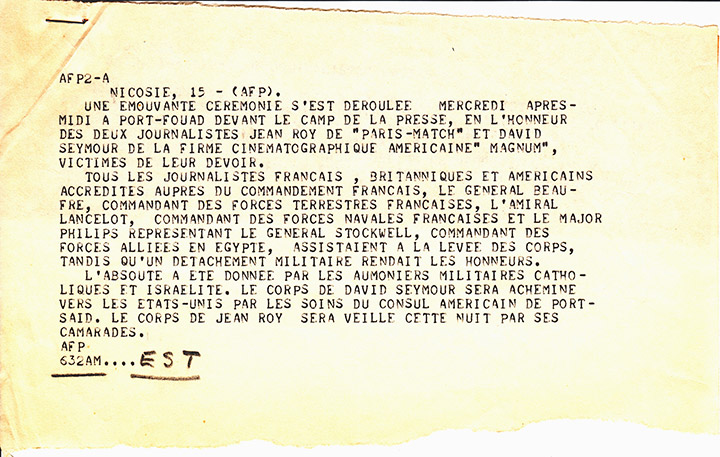

Chim made his way to Port Said, Egypt, on November 7, following the cessation of hostilities. In the company of several other journalists, Chim spent the following days photographing the destruction and mayhem in and around the city. On November 10, Chim and Jean Roy, a swashbuckling Paris Match photographer, drove 50 miles south of Port Said to photograph a prisoner exchange. Accounts of their deaths diverge, but the outlines are clear: Jean Roy drove their jeep past the Anglo-French lines, through no-man’s-land, toward the Egyptian lines. An Egyptian machine-gunner fired at the jeep, striking the photojournalists, and the jeep toppled into the Sweet Water Canal. Both Chim and Roy were killed.

A November 14 Agence France-Presse teletype report from Port Said describing the ceremony held when Egyptian authorities returned the bodies of Chim and French photographer Jean Roy, who were killed on November 10, 1956, © Chim Archive

A November 15, 1956, Agence France-Presse report from Nicosia further details the moving ceremony held at Port Fuad when the bodies were returned and notes that Chim’s body will be transported to the United States for burial, © Chim Archive

Breaking into a Food Store, Port Said

David Seymour (Chim), Breaking into a Food Store, Port Said, 1956, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.13

Port Said was devastated by the fighting. Desperate food shortages led to riots and, as seen here, the looting of food stores. Frank White, the Time-Life Paris bureau chief who traveled the city with Chim, recalled Chim’s fearlessness: “I remember many occasions when we had driven up to particularly nasty food riots…where we had been warned that everyone still had arms. Dave would have already made two, three, or a dozen pictures of the scene, but in each case he kept shooting in spite of our entreaties to leave. When making pictures, he seemed to be an entirely different man.”

Scraping Up Flour at a Looted Depot, Port Said

David Seymour (Chim), Scraping Up Flour at a Looted Depot, Port Said, 1956, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.37

Chim’s striking image depicts a boy whose face, centered and bathed in sunlight, has become covered in flour while he hurriedly scoops up every last grain from a looted depot. The photograph powerfully conveys the dire condition of the city’s population in the aftermath of the conflict.

In his memoir, Ben Bradlee described how he and Chim had witnessed the scramble for flour among the starving in Port Said: “We watched trucks unload sacks of flour into crowds that hadn’t eaten in three days. I can still see Schim [sic], a wisp of a man, standing on the jeep silhouetted against the darkling sky quietly photographing mob scenes of Egyptians ripping sacks of flour apart.” Bradlee’s description of people coated in flour echoes Chim’s photograph: “Black-haired and dark-skinned men and women were powdered a ghostly white as they swept the streets for a last fistful.”

Civilians, Port Said

David Seymour (Chim), Civilians, Port Said, November 9, 1956, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.12

This photograph of two injured civilians—bloody and sharing a single mattress—speaks directly to the war’s human toll. The paltry and inconspicuous orange halves, tucked under the pillow, were likely a key source of nourishment amid the food shortage. The photograph was taken on November 9, 1956, the day before Chim was killed.

Operation Port Said

David Seymour (Chim), Operation Port Said, 1956, gelatin silver print, Gift of Ben Shneiderman, 2008.122.10

This carefully composed image shows the destruction wrought on Port Said by Franco-British bombing raids. Rubble is strewn everywhere, a building in the background has been destroyed, and a broken water main has caused a flood, which is the source of a lovely but haunting reflection. The lone figure, perfectly centered, lends a sense of scale to the surroundings and is a reminder that civilians have suffered—and continue to suffer—amid war’s destruction.

Chim at Magnum

Chim’s career encompassed far more than taking photographs. As a founding member of Magnum Photos, a pioneering photographic cooperative that still thrives, he was a guiding force in its uncertain early years.

The idea for a new type of photo agency controlled by photographers, not editors, dated to the 1930s. Chim, just starting out in Paris, developed a close friendship with two young photographers, Robert Capa and

Fourteen years and two wars later, Chim in 1947 received a telegram informing him that he had been named vice president of the newly established Magnum Photos. Chim, Cartier-Bresson, English photographer George Rodger, and (for a brief time) William Vandivert joined Capa, who spearheaded the project, as the founding photographers of the innovative cooperative.

Magnum’s aim was editorial independence: rather than working on assignments handed out by magazines, Magnum photographers would generate and shoot their own stories and would retain copyright to their images. Magnum’s offices, at first in New York and Paris, would write captions and then sell the stories throughout the world. Magnum photographers became known for their integrity, dedication, and individual expression.

Magnum was formed at the right time. Capa and Cartier-Bresson were already famous, and picture magazines, whose circulation and revenue increased markedly in the late 1940s and 1950s (before television’s domination of journalism), had an endless appetite for quality photography.

As Magnum grew, Chim assumed greater organizational powers, planning group projects, reorganizing the Paris office, and traveling around Europe to talk to editors and agents about Magnum stories and guarantees. In 1953 he was placed in charge of Magnum’s complex finances, which he proved deft at managing. For Chim, who was unmarried and had lost his parents in the war, Magnum became an ersatz family. When tempers flared, Chim, with his cool demeanor, played mediator and peacemaker.

May 1954 proved a tragic month for the photo agency. Capa, Magnum’s president, stepped on a mine in Vietnam and was killed. Almost simultaneously word reached the agency that Magnum photographer Walter Bischof had fatally plunged into a gorge in the Andes. Magnum was rocked, and Chim, despite losing one of his oldest and closest friends, took matters in hand to ensure its survival. As Magnum photographer Eve Arnold noted, “Magnum was now in disarray….Chim helped forge ways and means for us to continue. Without his concern I question whether we would have stayed together.”

Chim’s press pass for the 1956 photokina fair in Cologne, where Magnum mounted its first major group exhibition, © Chim Archive

Chim assumed the presidency, which he held until his own death. In his brief tenure, he took steps to professionalize Magnum that had a lasting impact, including working out issues of money and control. But he also helped shape Magnum’s identity. In an essay he wrote for the 1956 photokina photography fair in Cologne, where Magnum had its first representative group exhibition, Seymour explained what Magnum photographers had in common: “The Magnum group cannot be considered a homogenous school of photography. It includes all varieties of individual talents, different technical approaches, and creative interests. There is, however, some unity, difficult to define, but still existing. There is a great affinity among Magnum photographers in terms of their photographic integrity and respect for reality, their approach to human interests and search for emotional impact, their preoccupation with composition and layout, and their awareness of narrative continuity.”

Seymour’s affection for Magnum was consuming and infectious. But it is also what persuaded him to cover the Suez Crisis in Egypt, where he would be killed. When colleagues tried to dissuade him from going, he explained, “I feel we cannot stay out of world events if we are to grow as a group in photography.”

Additional Resources

Children of Europe, UNESCO, 1949, with photos by David Seymour.

http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0013/001332/133216eb.pdf

“Somewhere in Europe: A Photographer Highlights the Drama of Post-War Youngsters,” UNESCO Courier 2, no. 1 (February 1949), 1, 5–9 [with photos and text by Seymour]

http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0007/000739/073912eo.pdf

Homeless Children, UNESCO, 1950, with some photos by David Seymour.

http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0013/001337/133713eb.pdf

The online Chim Archive contains hundreds of Seymour’s letters and documents.

Bibliography

Beck, Tom. David Seymour (Chim). London and New York, 2005.

Bondi, Inge. Chim: The Photographs of David Seymour. Boston, 1996.

David Seymour—“Chim.” New York [1966].

David Seymour, Chim. Valencia, 2003.

US Army Master Sergeant David Seymour during World War II, c. 1942–1944, © Chim Archive

View all photos by Chim in the collection