Civil War

These images are from a series created by artist Glenn Ligon describing the character of “Glenn,” in the style of runaway slave notices that were common in the era of slavery preceding the Civil War. Compare Ligon’s series to a real notice posted by Thomas Jefferson in 1769. What similarities can you find between the 1769 notice and Ligon’s recreation of the format?

Imagine being “Glenn.” What thoughts might you have upon seeing and reading this notice?

Glenn Ligon, Max Protetch Gallery, Burnet Editions Master Printers, Untitled, 1993, lithograph in black on wove paper, Gift of the Collectors Committee and Luhring Augustine Gallery, 2010.57.10

In The Spirit of War, a rugged mountain landscape provides the backdrop for a medieval wartime scene: knights on horseback ride into battle, a distant settlement burns, and a mother and child cower on the ground. A castle rises from the jagged rocks, framed by gathering storm clouds that portend destruction. Jasper Francis Cropsey described the scene of his painting as “promising naught but the uncertain and gloomy future of warlike times.”

By contrast, its companion piece, The Spirit of Peace (Woodmere Art Museum, Philadelphia), shows a landscape with tiny figures engaged in various recreational pursuits. The paintings’ twinned themes of war and peace would have had an immediate emotional significance for Cropsey’s audience. The recent Mexican War (1846–1848) and the debate over whether the western territories would join the nation as free or slave states contributed to the strained national atmosphere in the decade preceding the Civil War.

Read the poem “Beat! Beat! Drums!” by Walt Whitman, which was written about the impending Civil War. What sentiments are expressed in that poem? How does the sentiment of the poem compare with what’s shown in this painting? Imagine one of the people depicted in the painting is the “drummer” from the poem. What do you think might happen next?

Jasper Francis Cropsey, The Spirit of War, 1851, oil on canvas, Avalon Fund, 1978.12.1

This painting, completed just three years before the Civil War began, may be an expression of Northern antipathy toward the gentry of the South.

A well-dressed man leans casually on the right, hands tucked in his pockets and legs crossed, while a hardworking blacksmith labors on the left. The dog might be a reference to the breeding of animals for sport and show, an idle pursuit of Southern aristocracy during this period. During the war, the greyhound was one of the symbols of the Confederacy in anti-Southern political satires. The white poster on the right depicts a man (who resembles the Grim Reaper) running with scythe in hand above the misspelled text “Stop Theif!”—reminding the viewer that time is precious and not to be wasted.

Look closely at this painting. What details do you notice? What is a symbol? Are there any parts of this painting that might serve as a symbol? What might they symbolize? Tell students or ask them whether they recall Aesop’s fable about the ant and the grasshopper. Are there any connections that can be made to this painting?

Abolitionist minister Henry Ward Beecher (in response to the caning of Sumner) said in 1856 that "the symbol of the North is the pen; the symbol of the South is the bludgeon." What do you think he meant by that statement?

Frank Blackwell Mayer, Leisure and Labor, 1858, oil on canvas, Corcoran Collection (Gift of William Wilson Corcoran), 2014.136.111

This painting represents voting on an election day. The two men in the foreground are engrossed in conversation, and the man on horseback to the left reads the newspaper aloud—activities that suggest study and debate in preparation for voting. The lively hand gestures of the two men who beckon toward the building in the distance and a third at left who points his riding crop direct attention toward the polling station. The artist’s inclusion of a small group of African American spectators standing apart from the larger gathering outside the polling place may allude to the issues at stake.

Historians suggest this image may depict either the creation in 1845 of the first nationwide Election Day in the United States, or a pivotal Maryland state election that year.

Pick a person depicted in this artwork. What might that person be thinking about, feeling, and wanting to do?

Alfred Jacob Miller, Election Scene, Catonsville, Baltimore County, c. 1860, oil on academy board, Corcoran Collection (Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Lansdell K. Christie), 2014.79.26

Look closely at this painting. What details do you notice?

Two Union soldiers listen as the regimental band plays “Home, Sweet Home.” Winslow Homer himself visited the front in 1861 and 1862. The title of Homer’s painting evokes the “bitter moment of homesickness and love-longing” that the song inspired in the soldiers. With surely intended irony, the title also refers to the soldiers’ “sweet” home, shown with all of the domestic details—a small pot on a smoky fire, a tin plate holding a single piece of hardtack—that Homer, who did the cooking and washing when he was at the front, knew intimately.

Listen to the folk song “Home Sweet Home,” performed by Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs. What does it make you think of? Alternatively, play the song and have students illustrate what the song brings to mind. How do the students’ illustrations compare with Homer’s painting? How do you imagine the men depicted in this painting might be feeling?

Winslow Homer, Home, Sweet Home, c. 1863, oil on canvas, Patrons’ Permanent Fund, 1997.72.1

At the beginning of the Civil War, photographer Timothy O’Sullivan was working in Mathew Brady’s Washington, DC, studio under Alexander Gardner. Gardner, O’Sullivan, and a number of other qualified photographers were actively involved in photographing the war.

O’Sullivan photographed military men at camp, swimming, relaxing, in battle, wounded, and dead. He also captured images of the landscape, bridges during construction and after destruction, and battlefields littered with the bodies of dead soldiers.

Most people who viewed this image at the time it was created would have almost certainly never seen a casualty of war before. How do you imagine they would have reacted?

Timothy H. O’Sullivan, Field Where General Reynolds Fell, Gettysburg, July 5, 1863, July 5, 1863, albumen print, Gift of Mary and Dan Solomon and Patrons’ Permanent Fund, 2006.133.111

In 2001, artist Sally Mann began a project to photograph Civil War battlefields, starting in Antietam—site of the bloodiest one-day battle in US history—and moving on to many others across Virginia. This photograph was taken at the battlefield of Cold Harbor, but any trace of fighting or death is conspicuously absent from this photograph.

To make this and other photographs in the series, Mann worked the same way that Civil War photographers such as Mathew Brady would have, using processes that required bringing a portable darkroom in order to develop photos on the spot.

What information can we learn from looking closely at this photo? What information is left out of the image?

Sally Mann, Battlefields, Cold Harbor (Battle), 2003, gelatin silver print, Gift of the Collectors Committee and The Sarah and William L Walton Fund, Image © Sally Mann, 2016.194.2

Alexander Gardner worked in photographer Mathew Brady’s studio. After witnessing the battle at Manassas, Virginia, Brady decided that he wanted to make a record of the war using photographs. Brady dispatched more than 20 photographers, including Gardner, throughout the country. Each man was equipped with his own traveling darkroom so that he could process the photographs on site.

In November 1861, Gardner was granted the rank of honorary captain on the staff of General George McClellan. This put him in an excellent position to photograph the aftermath of the Battle of Antietam. On September 19, 1862, two days after the battle, Gardner became the first of Brady’s photographers to take images of the dead on the battlefield. Gardner went on to cover more of the war’s terrible battles, including Fredericksburg, Gettysburg (where this image was taken), and the siege of Petersburg.

What iconic photos have you seen from a current war? What elements of those photos struck you? What do you think the photographer was aiming to convey or capture with those images? How do these images from the Civil War compare with images from 21st-century wars?

Alexander Gardner, A Sharpshooter's Last Sleep, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, July 1863, 1863, albumen print, Gift of Mary and Dan Solomon and Patrons’ Permanent Fund, 2006.133.73

Because photographs had become much easier to produce by the start of the Civil War, they became less expensive. Aware that he might return changed or not return at all, the average soldier could have his portrait photograph taken before leaving for war. A photo like this may have been the only photo ever taken of many of these soldiers. The portrait photos were often kept safe in small but ornate frames such as the one shown in this image.

The soldier shown in this portrait likely knew it was a major occasion when he decided to have his photograph taken. What decisions did he make about his clothing, appearance, and expression? What do you think he wanted viewers to think about him, based on the decisions he made about how he would look?

American 19th Century, Portrait of a Soldier, 1860s, tintype, Robert B. Menschel and the Vital Projects Fund, 2012.40.3

The central image in this painting is of a freed black man in the uniform of the US Colored Infantry, with broken shackles in his hands and on the ground. In a gesture of Union sympathy, he stands beside a pole on which the US flag is raised, while the flag of South Carolina lies in tatters beneath his feet. Union support is also expressed by the mounted soldier to the left, who waves the Union flag in the air as he drags the first Confederate national flag.

This print differs from similar emancipation-themed prints from the period, in which the black man is typically portrayed as prostrate before a paternalistic white man.

The tropical trees may be South Carolina palmettos, while the ruins may refer to the upheaval of the old order in the South, or the state of the war-ravaged nation in general. Atop the ruins is an eagle devouring a snake, a motif which conveys that good has triumphed over threatening foes. During the Civil War, the eagle assumed its role as a symbol of the nation in Union propaganda, while the serpent represented the Confederacy.

What is an allegory? If you were to draw an allegory of freedom, what would it look like?

American 19th Century, Allegory of Freedom, 1863 or after, oil on canvas, Gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch, 1955.11.4

This engraving depicts a Union sharpshooter, positioned in a tree for camouflage, who takes aim at an unseen enemy. Newer rifles used in the Civil War meant that soldiers like the sharpshooter depicted here could be positioned at a much farther distance from their targets, disconnecting them from death and the consequences of their actions.

About his experience documenting the sharpshooters, Winslow Homer said, “The above impression struck me as being as near to murder as anything I could think of in connection with the army [and] I always had a horror of that branch of service.”

Imagine seeing this image as a regular member of the public during the Civil War. What reaction might you have to it? What reaction do you think the artist might have wanted viewers to have when seeing it?

American 19th Century, Winslow Homer, The Army of the Potomac - A Sharp-Shooter on Picket Duty, published 1862, wood engraving, Print Purchase Fund (Rosenwald Collection), 1958.3.18

This imaginary scene is set against the east facade of the US Capitol in Washington, DC. Led by the classic image of the goddess of Liberty driving a chariot, Lincoln and his officers are in turn followed by Union army cavalry. The full-bearded, sword-wielding general at the right resembles Ulysses S. Grant.

A. A. Lamb balanced the Union army with a crowd of freed people cheering and waving at the left, their recent emancipation signified by the broken chains on their wrists. A ball and chain, shackles, and whip lie in the right foreground next to a trampled Confederate flag. This painting, like many other images from the time, depicts a scene in which emancipated slaves look in gratitude upon whites in positions of power. Look carefully at this picture. Who are being portrayed as the heroes of this story? How can you tell? How might the painting have been different if created for a different audience?

Compare this image with the text of the Emancipation Proclamation. Can you draw an arrow between certain paragraphs of the proclamation and certain parts of this painting? Who do you think the main audience for the Emancipation Proclamation was? Is it the same as this painting?

A. A. Lamb, Emancipation Proclamation, 1864 or after, oil on canvas, Gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch, 1955.11.10

Into Bondage is a powerful depiction of enslaved Africans being forcibly taken to the Americas. Shackled figures with their heads hung low walk solemnly toward slave ships on the horizon. A woman at left raises her bound hands, guiding the viewer’s eye to the ships. The male figure in the center pauses on the slave block, his face turned toward a beam of light emanating from a lone star in the softly colored sky, possibly suggesting the North Star. The concentric circles are a motif frequently employed by Aaron Douglas to suggest sound, particularly African and African American song.

In 1936, Douglas, considered a leader of the Harlem Renaissance, was commissioned to create a series of murals (of which this is one) for the Texas Centennial Exposition in Dallas. Installed in the Hall of Negro Life, his four paintings charted the journey of African Americans from slavery to the present. The Hall of Negro Life opened on Juneteenth (June 19), a holiday celebrating the end of slavery.

What rights had black Americans gained by the 1930s, at the time when Douglas made this mural series? What rights and freedoms did they have yet to gain? Why do you think Juneteenth, a commemoration of the abolition of slavery, is an important holiday to celebrate?

Aaron Douglas, Into Bondage, 1936, oil on canvas, Corcoran Collection (Museum Purchase and partial gift from Thurlow Evans Tibbs, Jr., The Evans-Tibbs Collection), 2014.79.17

This print, published in the popular journal Harper’s Weekly, depicts various spheres of “the influence of woman” in the war efforts during the Civil War. Many Americans would have turned to Harper’s Weekly illustrations and articles for information about the war.

Women had varied roles in the war: they served as cooks, nurses, clothes washers, and menders; they organized drives to collect food and supplies needed by troops; and they provided care to recovering soldiers injured in battle. Some even fought as soldiers, disguising themselves as men to be able to enlist. (Women were barred from enlisting in both the Union and the Confederacy.) Many black women, both free and enslaved, served in these roles, though they were less commonly depicted as being part of the war efforts.

Look closely at this drawing. Can you identify the different roles or jobs women had in the war by looking at the details that are included? If you were to make a drawing of women’s roles in more recent wars (e.g., the war in Afghanistan), what would you include?

American 19th Century, Winslow Homer, Our Women and the War, published 1862, wood engraving on newsprint, Avalon Fund, 1986.31.261

Commissioned from the celebrated American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens in the early 1880s and dedicated as a monument in 1897, the Shaw Memorial has been acclaimed as the greatest American sculpture of the 19th century. The memorial commemorates the valiant efforts of the 54th Massachusetts, the first Civil War regiment of African Americans enlisted in the North. Recruits came from many states, encouraged by African American leaders such as the great orator Frederick Douglass, whose own sons joined the 54th. The unit was commanded by 25-year-old Robert Gould Shaw, the Harvard-educated son of dedicated white abolitionists.

On the evening of July 18, 1863, the 54th Massachusetts led the assault upon the nearly impenetrable earthworks of Fort Wagner, which guarded access to the port of Charleston, South Carolina. The steadfastness and bravery of the 54th were widely reported, providing a powerful rallying point for African Americans who had longed for the chance to fight for the emancipation of their race. By the end of the war, African Americans composed 10 percent of the Union forces, making crucial contributions to the final victory of the North.

Explore with your students the role of commemorative sculpture.

Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Shaw Memorial, 1900, patinated plaster, U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site, Cornish, New Hampshire, X.15233

Elizabeth Catlett dedicated her art to the African American experience. She believed that “art can prepare people for change; it can be educational and persuasive in people’s thinking.”

Catlett grew up in a middle-class neighborhood in Washington, DC, and studied art at Howard University. After she graduated, she taught high school in Durham, North Carolina. She later moved to Mexico, where she worked with the Taller de Gráfica Popular (TGP), a famous workshop in Mexico City dedicated to graphic arts promoting leftist political causes, social issues, and education. At the TGP, she and other artists created a series of linoleum cuts featuring prominent black figures, as well as posters and other materials to promote literacy in Mexico. In this work she depicted Harriet Tubman, the abolitionist who helped many escape slavery via the Underground Railroad.

What character traits would you use to describe Harriet Tubman based only on this depiction of her? Based on what you know of her life and work, is there anything you would add to that list?

Elizabeth Catlett, Taller de Gráfica Popular, Untitled (Harriet Tubman), 1953, linocut, Reba and Dave Williams Collection, Florian Carr Fund and Gift of the Print Research Foundation, 2008.115.37

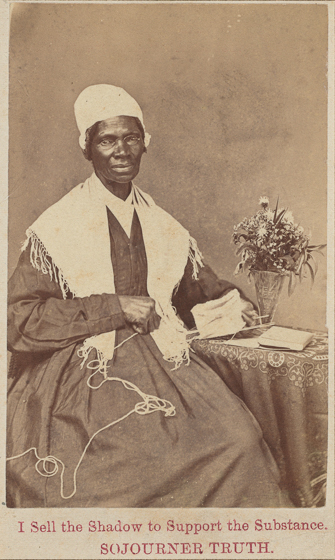

This is a carte-de-visite—a small photo cut and placed on a card. They were popular during the late 19th century as photos to be exchanged between people on holidays or other occasions. Compared to other forms of portraiture, cartes-de-visite were relatively inexpensive and accessible to many people, if they could get to a studio that would produce them.

Sojourner Truth, the woman depicted, was a famous abolitionist who advocated for the inclusion of black soldiers in the Union army during the Civil War and fought tirelessly throughout her life for women’s suffrage. The phrase “I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance” refers to how Truth strategically embraced photography and distributed photos of herself as a way to promote her positions and secure financial support to fund her efforts.

What words would you use to describe this woman, using only the information we can gather from the photo? Many people consider her a hero. Do you agree?

American 19th Century, Sojourner Truth, 1864, albumen print mounted on card (carte-de-visite), Pepita Milmore Memorial Fund, 2014.19.1

A Pastoral Visit depicts a family welcoming their elderly pastor to Sunday dinner—a frequent occurrence in both black and white rural parishes that could not afford parsonages. According to tradition, the pastor is served first, and following the meal he will be presented with the cigar box containing the congregation’s weekly contribution and the cloth-wrapped fruit at right. The banjo, prominently placed at the center of the composition, may indicate an after-dinner musical interlude.

Richard Norris Brooke had ample opportunity to study the interior depicted; it was located in a residence near his home in Warrenton, Virginia, where he painted the canvas. The figures in the painting are based upon his Warrenton neighbors: George Washington, Georgianna Weeks, and Daniel Brown. Brooke was one of many artists to depict African American life in the 1870s and 1880s, inspired by the dramatic social changes during Reconstruction, when black citizens were granted voting rights and protection under the Constitution. Unlike many of his peers, he portrayed his subjects with a degree of humanity and dignity rare in contemporary depictions of African Americans.

What was the period of Reconstruction? Read an anonymous notice posting rules for black laborers in Tennessee from 1867, likely authored by a vigilante group like the Ku Klux Klan. Do you think the scene in this painting represents the overall experience of freed black Americans during that time period? Why or why not?

Richard Norris Brooke, A Pastoral Visit, 1881, oil on canvas, Corcoran Collection (Museum Purchase, Gallery Fund), 2014.136.119