Artists who headed south toward Naples and beyond encountered a landscape that married the allure of classical antiquity with the drama of volcanic activity. Few subjects rivaled the awe-inspiring sight of a volcano erupting, deemed by one painter to be “the most terrible and the most magnificent spectacle” offered by nature. Climbing to the rim to sketch was a way for artists to prove their mettle. In southern Italy they had their pick, including Mount Vesuvius near Naples and the Sicilian volcanoes Mount Etna and Mount Stromboli. Vesuvius, destroyer of ancient Pompeii, most ignited the artistic imagination. Easily accessible, it spewed forth a fairly regular succession of minor rumblings and emissions, punctuated by vigorous eruptions of choking dust-clouds and red-hot lava. Several powerful explosions in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries sent the surrounding population fleeing the flames and smoke — and artists toward them to sketch the pyrotechnic glory.

A deep attachment to nature took root in European art of the late eighteenth century. Nurtured by philosophical writings, scientific inquiry, and poetic sentiment, the quest for naturalism led artists to embrace open-air painting decades before the impressionists famously took their canvases outdoors. Aspiring painters were taught that truthful rendering of nature could be learned only from direct observation — not in the studio from a master or from a manual. Venturing outside with portable paint kits, they trained their eyes and hands to transcribe in quick oil sketches the ephemeral effects of light and atmosphere, the fleeting shape of a cloud, the textured bark of a tree, or the rush of a waterfall. Rapidness was key, according to Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes, the most influential exponent of the practice: shifting conditions meant an oil sketch would no longer be true to nature if more than two hours were spent working on it. Capturing the essence of a motif was more important than recording all the finicky details.

Rome was the center of the oil-sketch tradition. Filled with monuments, steeped in classical associations, and graced with picturesque environs animated by a steady, exquisite light, the city beckoned bands of young artists from France, Germany, Scandinavia, Great Britain, and elsewhere to learn from its splendor. Returning home, they continued painting outdoors, spreading the practice among those who never made an Italian journey.

Painted freely and thinly on sheets of paper and small cuts of canvas or board, open-air oil sketches were exercises in skill intended neither for sale nor for exhibition. Although some were later worked up in the studio, most remained out of public view, consulted as private artistic resources for the larger polished landscapes on which painters staked their reputations. Yet to modern eyes the freshness and immediacy of these glimpses of nature are what make them so appealing. This exhibition brings together some one hundred outdoor oil sketches by artists across a spectrum of fame, from Camille Corot and John Constable to painters largely forgotten or unknown. Their quick yet luminous responses to nature are arranged thematically — from views of Rome and southern Italy to studies of trees and clouds — to reflect the way artists themselves organized these painted observations made “in the field.”

The artist brings back the result of his observations, and the studies that he has made in the countryside . . .

In looking at his work, he remembers perfectly the sites that he has copied.

All the phenomena that he has admired retrace themselves in his memory.

—Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes, 1799

Rome and the Campagna

André Giroux, Santa Trinità dei Monti in the Snow, 1825/1830, oil on paper on canvas, Chester Dale Fund, 1997.65.1

In Rome, marvelous views greeted artists at every turn. Set against the backdrop of the Sabine Hills, church towers rose up next to ancient ruins — all bathed in the magical light of Italy. Such was the city’s lure that some northern visitors stayed for years or never returned home. Artists built vibrant expatriate communities that welcomed new arrivals and introduced them to the best sites and methods for outdoor painting.

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, The Island and Bridge of San Bartolomeo, Rome, 1825/1828, oil on paper on canvas, Patrons' Permanent Fund, 2001.23.1

In the surrounding countryside, known as the campagna, these artists stayed at the same inns and hostelries and, though eager to claim their own remote spots, often ended up easel to easel at the same romantic prospects. Crossed by the Tiber and Aniene Rivers and the highways radiating from ancient Rome, the campagna was dotted with majestic ruins, tombs, and huge arching aqueducts, while flocks of sheep, herds of buffalo, and bandits also roamed its fields and hills. Painters saw in the region a timeless, elegiac beauty arising from its striking mixture of nature, light, and classical antiquity.

Léon-François-Antoine Fleury, The Tomb of Caecilia Metella, c. 1830, oil on canvas, Gift of Frank Anderson Trapp, 2004.166.16

The South of Italy:

Naples, Capri, and Volcanoes

Giuseppe de Nittis, Eruption of Vesuvius, 1872, oil on wood panel, Fondation Custodia, Collection Frits Lugt, Paris

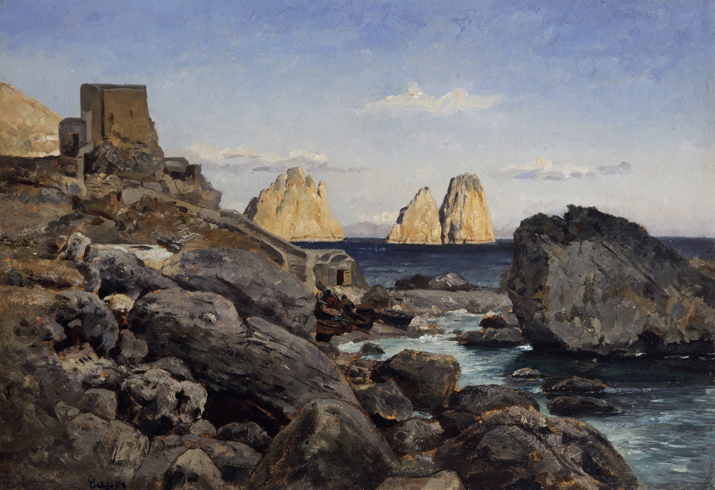

August Kopisch, View of Faraglioni near Capri, oil on wood panel, Fondation Custodia, Collection Frits Lugt, Paris

Almost as thrilling as an erupting volcano was the perilous journey to Capri in the Gulf of Naples. Until the early nineteenth century, many travelers avoided the island, deterred by the dangers of its rocky coastline. But tales of Capri’s captivating beauty, embodied in dazzling oil sketches made by the few artists who braved the conditions, convinced others to venture there. Those who did delighted in the island’s craggy limestone cliffs and white buildings set against an azure sky, as well as its famed faraglioni, majestic rock formations jutting from the inky-blue sea.

Simon Denis, View near Naples, c. 1806, oil on paper on canvas, Chester Dale Fund, 1998.21.1

Water: Coasts and Cascades

Baron François Gérard, A Study of Waves Breaking against Rocks at Sunset, oil on millboard, Private Collection, London

In foggy weather that sailors call sea mist, the water is gray and the color of the atmosphere, above all when it is tranquil; but if the sea is rough, it takes on different tones: blackish green, greenish blue, darkened violet mixed with the foamy white of the cresting waves that grow and roll and break into each other.

—Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes, 1799

The confluence of water and land beckoned artists to picturesque coastlines from Italy and France to Denmark and Germany. Painters could try their skill at depicting changing weather conditions, liquid reflections of sky and earth, pale sandy beaches, frantic waves, and rocky cliffs eroded by sea and wind. Inland, lakes and waterfalls served a similar purpose.

Christian Ernst, Bernhard Morgenstern, Waterfall in the River Traun, Bavaria, 1826, oil on paper, Fondation Custodia, Collection Frits Lugt, Paris

Water in motion is one of the most demanding motifs to paint. Flowing in cascades or surging in the sea, it never holds its shape, all the while changing color as it shifts from frothy whites to transparency to reflecting the palette of its surroundings. Rushing water moves faster than any brush, yet the quickness of oil sketching often matched the subject. In many sketches, loose brush marks fly and descend and collide to suggest a rapid chute of water and foamy waves crashing violently against rocks.

Jean Joseph Xavier Bidauld, View of the Waterfalls at Tivoli, 1788, oil on paper on canvas, Gift of Fern and George Wachter, 2005.140.1

Rocks, Grottoes, Caves

Jean-Baptiste Adolphe Gibert, Interior of a Cave, oil on paper, Fondation Custodia, Collection Frits Lugt, Paris

The variety of shapes, textures, and colors of the earth’s crust appealed to the sculptural and painterly sensibilities of land- scape artists working in the open air. Like architectural ruins, geological formations also prompted painters to contemplate time. Advances in earth sciences dwarfed a sense of human history by revealing the effect of monumental forces, from geothermal activity to water and wind erosion, in shaping cliffs, outcrops, and caves over millennia. Eroded rocks and weathered outcroppings captured attention in northern landscapes, while in Italy artists were particularly taken by the caves and grottoes that riddled the volcanic terrain. Their grandeur and mystery matched that of the ancient Etruscan and Roman architectural ruins that also defined this land.

Carl Wilhelm Götzloff , Limestone Rocks, Sorrento, 1858, oil on paper, mounted on cardboard, Fondation Custodia, Collection Frits Lugt, Paris

Trees

Fritz Petzholdt, Tree Crowns in a Forest (Ariccia?), c. 1832, oil on paper, Fondation Custodia, Collection Frits Lugt, Paris, Gift of John Schlichte Bergen and Alexandra van Nierop, Amsterdam

Considered the greatest ornament and noblest element of the landscape, the tree was also acknowledged as a fiercely complicated motif to paint. The diversity of arboreal size, shape, and color meant that no single ideal existed for artists to emulate. In an era that saw the introduction of a modern botanical classification system and the emergence of forest management as a profession, artists found themselves alongside scientists wandering in the woods. Both strove to understand these natural treasures through firsthand observation and sketching. In their oil studies, however, artists generally favored expressing the character of a species by conveying distinctive features in just a few lines or strokes. “Sufficient resemblance” was the goal, according to the writer of a treatise on depicting trees. “It is not necessary to become a perfect Botanist to delineate a leaf.”

André Giroux, Forest Interior with a Waterfall, Papigno, 1825/1830, oil on paper, Gift of Mrs. John Jay Ide in memory of Mr. and Mrs. William Henry Donner, 1994.52.4

Skies and Atmospheric Effects

John Constable, Cloud Study: Stormy Sunset, 1821-1822, oil on paper on canvas, Gift of Louise Mellon in honor of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, 1998.20.1

Stormy or serene, overcast or brilliant, looming over a low horizon or shimmering through foliage, the sky offered itself as an endlessly variable and wondrous element of any landscape. Painting manuals urged artists to observe atmospheric effects at different times of day, in different seasons, and under different conditions. The weather transformed not only the appearance of the landscape but also that of the rooftops and buildings that caught the eye of the artist. The burgeoning field of meteorology helped drive the interest; notes on the weather dominate the diaries and correspondence of many artists of the era. The formation of clouds, cotton-like or wispy, were of particular concern. The quality of light and range of colors in the sky at sunrise and sunset could be spectacular, but even mastering the art of gradations of gray was a useful skill, especially for artists working in the north. Landscapes sketched in the absence of the sun could be enchanting, where forms begin to lose their contours in the mist or descending darkness.

Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes, Study of Clouds over the Roman Campagna, c. 1782/1785, oil on paper on cardboard, Given in honor of Gaillard F. Ravenel II by his friends, 1997.23.1

The exhibition is organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, the Fondation Custodia, Collection Frits Lugt, Paris, and the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, UK.