Born 1894, Braddock, Pennsylvania

Died 1967, West Virginia

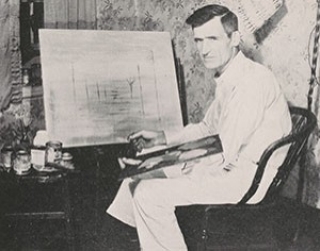

“You remember the old saying,” Patrick Sullivan once explained. “‘A lie is the truth in disguise.’ It is my intention to bring truth out in all its glory on my canvases . . . a sort of parable in picture form.”[1] Specifically, Sullivan created quietly striking landscapes to reveal such lessons, recognizable for the symmetrical compositions and “clean and plain” look that he deemed essential to art. Similarly, he valued his technical expertise with paint handling, a skill he attributed to his occupation as a house painter. Working in a corner of his West Virginia bedroom, Sullivan mixed his own oil paints and sometimes worked over painted surfaces with sandpaper to generate varied textures.

Sullivan produced only nineteen paintings that are known today, a number that would have been significantly smaller had New York dealer Sidney Janis not encountered Sullivan’s art at the Society of Independent Artists show in 1937. Immediately taken by its emotional power, he purchased several paintings and encouraged the artist’s development.[2] Then in 1938, at Janis’s prompting, Alfred Barr included Sullivan in his Masters of Popular Painting exhibition at MoMA. This show introduced contemporary, self-taught individuals as artists of stature and thereby validated their work as another branch of modernism.

Though Janis suggested that Sullivan’s imagery was coded as Christian—he saw a cross, Star of Bethlehem, and Holy Grail in The Fourth Dimension—the artist’s paintings seem less concerned with explicit religious meaning than with one’s relationship to an “infinite system of worlds and wonders.”[3] Three crosses in Solitude undeniably suggest themes of suffering and penance. Yet Sullivan places them atop a distant hill, as if to suffuse the foreground trees with their symbolism. While one tree has fallen and shattered, the other is robust and firmly rooted. A subtle cross emerges from the foliage of the standing tree, transforming it into a reflection, perhaps, of vitality amid desolate circumstances.

Elaine Yau

[1] Baker 1979, 54.

[2] Baker 1979, 58.

[3] Patrick Sullivan, quoted in Janis 1942, 70.

Baker, Gary E. Sullivan’s Universe: The Art of Patrick J. Sullivan, Self-Taught West Virginia Painter. Wheeling, WV: Oglebay Institute, 1979.

Janis, Sidney. They Taught Themselves: American Primitive Painters of the 20th Century. Foreword by Alfred H. Barr Jr. New York: The Dial Press, 1942.