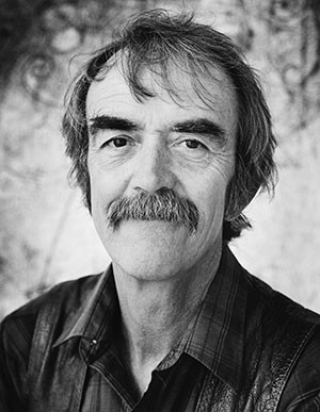

Born 1937, Bedford, Indiana

With repurposed materials and characteristic wit, William Wiley’s Canjo relishes the inventiveness that transforms simple materials into an aesthetically rewarding object. A plain woven cord binds together seven empty coffee cans that Wiley has attached to a found tree branch. Strung with a single wire, Wiley’s down-home take on the banjo shares many similarities with folk instruments like the one-stringed diddley bow, whose easy assembly and bluesy sound continue its appeal for guitar enthusiasts today.

Canjo’s folk sensibility not only relates to Wiley’s talent as a guitarist and harmonica player, it also embodies the participatory aspects of music making that he developed after joining the art faculty at the University of California, Davis, in 1962. Alongside his colleagues—among them Robert Arneson, Roy De Forest, and Bruce Nauman—Wiley thrived in this informal environment. He experimented energetically across media, eventually forging an idiosyncratic vocabulary that incorporated drawing, assemblage, painting, and absurdist texts. His admiration for musicians and independent-minded artists merges in a series of hand-carved, functional guitar sculptures of the 1980s that he dedicated to figures like Muddy Waters and Joseph Beuys. In the spirit of extending such reciprocity, Wiley once joked that he wanted buyers of his banjos and guitars to send him a cassette of music made with his instruments, but he judged the idea too imposing. Nevertheless, his openness to exchange echoes in the correspondence he maintained with enigmatic Chicago artist H. C. Westermann, whose outsider status encouraged Wiley to pursue his own dadaist- and surrealist-inflected works.

In 1988 Canjo was displayed with an anonymously made cigar-box violin in the exhibition Not So Naïve at San Francisco Craft and Folk Art Museum. A multimedia assemblage by Bruce Conner paired with a television-and-glass-jar group by Howard Finster were also on view, along with a De Forest painting and one of Nellie Mae Rowe’s dreamlike drawings. This show among others exemplified the Bay Area’s disregard for convention, which created space for curators and artists to explore openly the connections between vernacular and mainstream art.

Elaine Yau

Moser, Joann, John Yau, and John Hanhardt. What’s It All Mean: William T. Wiley in Retrospect. Washington, DC: Smithsonian American Art Museum, with the University of California Press, Berkeley, 2009.

William T. Wiley: Struck! Sure? Sound / Unsound. With Terrie Sultan and Christopher C. French. Washington, DC: Corcoran Gallery of Art, 1991.