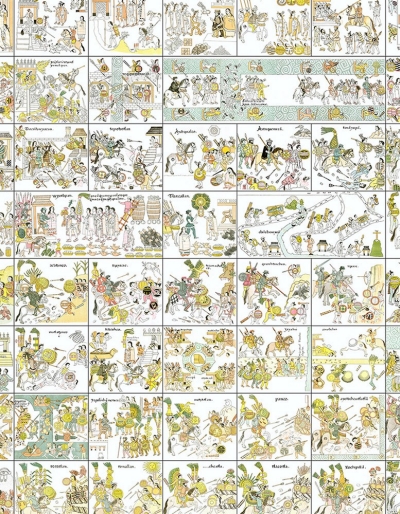

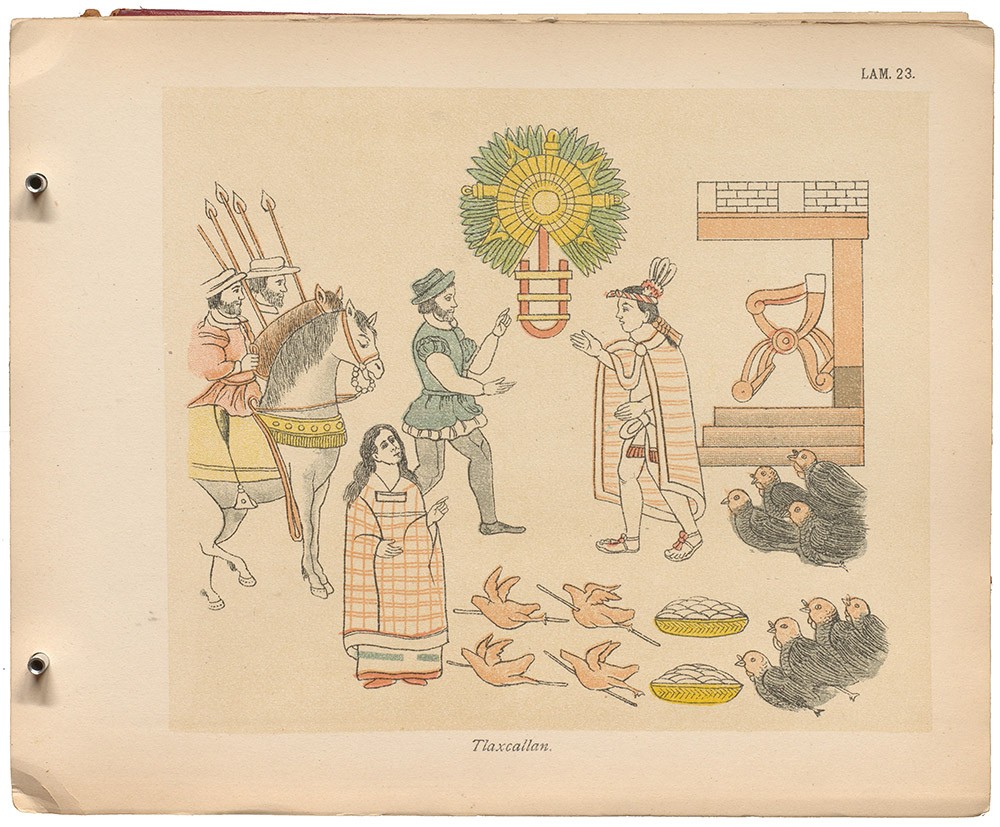

Media archaeology has an uncomfortable relationship with military violence. Consider Friedrich Kittler’s “Rock Music: A Misuse of Military Equipment” (2013), or references in media-theoretical writings to Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow (1973; the title referring in part to the parabolic arc made by a V-2). Media archaeology also tends to have a US/European North Atlantic bias, although this is beginning to change—for example, Brian Larkin’s Signal and Noise (2008), or Delinda J. Collier’s Media Primitivism (2020). The history of the Lienzo de Tlaxcala (first iteration c. 1552) across five centuries activates these issues in various ways. The Lienzo provides a visual history of military violence: telling how the Tlaxcalans (with a little help from Hernán Cortés and his European soldiers) conquered the capital of their pre-Hispanic enemies, the Aztecs, and went on to seize lands far beyond the limits of the Aztec Empire. It is a story that connects the European North Atlantic to the Mesoamerican world: not simply because European soldiers were co-opted to pursue the ends of their Native American allies, but also because the Lienzo itself (or, more accurately, one of its three original copies) was designed as a gift to be sent across the Atlantic to Emperor Charles V. And it is a story of media and remediation across 500 years. Its images (painted on cloth) were based in part on an earlier, European-style bound book on Mesoamerican bark paper (1540s), and the finished cloth was then repeatedly copied and remediated in the centuries to come: with black ink on European paper (1580s), watercolor on cloth (1779), pencil on tracing paper (1860s), lithograph (1840s and 1890s), and, most recently, a digital re-creation (2012).

In the 1540s, European woodcuts proved to be a key model for the pre-Lienzo “Texas Fragment,” due in part to the visual homologies between late pre-Hispanic images (bold, black outlines; solid fields of color) and woodcuts. Indigenous artists borrowed woodcuts’ frame lines and techniques of overlap to create a visual narrative of alliance with Cortés. Three centuries later, during the French occupation of Mexico in the late 1860s, tracing paper was the medium by which two artists (one French, one Mexican) created copies of the circa 1552 and 1779 iterations of the Lienzo (both of which had ended up in Mexico City’s Museo Nacional). At this point, the 16th-century cloth disappeared, leaving colored tracings behind as our main record of this still-lost document. (In 1892 these tracings would be used to create a large-format, lithographed “facsimile.”)