My book manuscript analyzes a range of depictions of enslaved people from the antebellum period, addressing the multifarious ways that supporters of enslavement applied art in justifying their beliefs. A variety of examples of antebellum art reflected the rhetoric of pro-slavery apologists by representing enslaved people in an optimistic light, and they also worked to undermine abolitionists’ powerful use of visual culture. The works of apologists reflect trends broadly categorized as concealment, which I organized into a series of subthemes, including physical concealment, idealization, secrecy, and destruction. In idealizing slavery and thereby concealing the horrific aspects of the institution, some of these best-known works offer a rosy romanticism. Literal methods of concealment were undertaken in some cases, and strict secrecy was maintained in the creation of other works. Anger toward abolitionists resulted in outright destruction (of artworks, of structures, and ultimately of bodies) in extreme cases. Suspicion regarding slavery at nearly every turn led to cover-up and this manifested in disparate ways. My research explores these little-acknowledged trends within slavery-related art; drawing from a range of media, this project addresses art history’s covert implication in support of slavery.

The artists addressed in this project did not experience the hardship of slavery themselves. Rather, they illustrated their understanding of it to suit their beliefs or purposes—or more likely, those of their patrons. However, works and actions such as these mediate our view of slavery today. My goal therefore is not to probe the difficulties of slavery, but rather to locate and acknowledge how a visual culture of cover-up affected the coeval political climate and continues to cloud our view of the past.

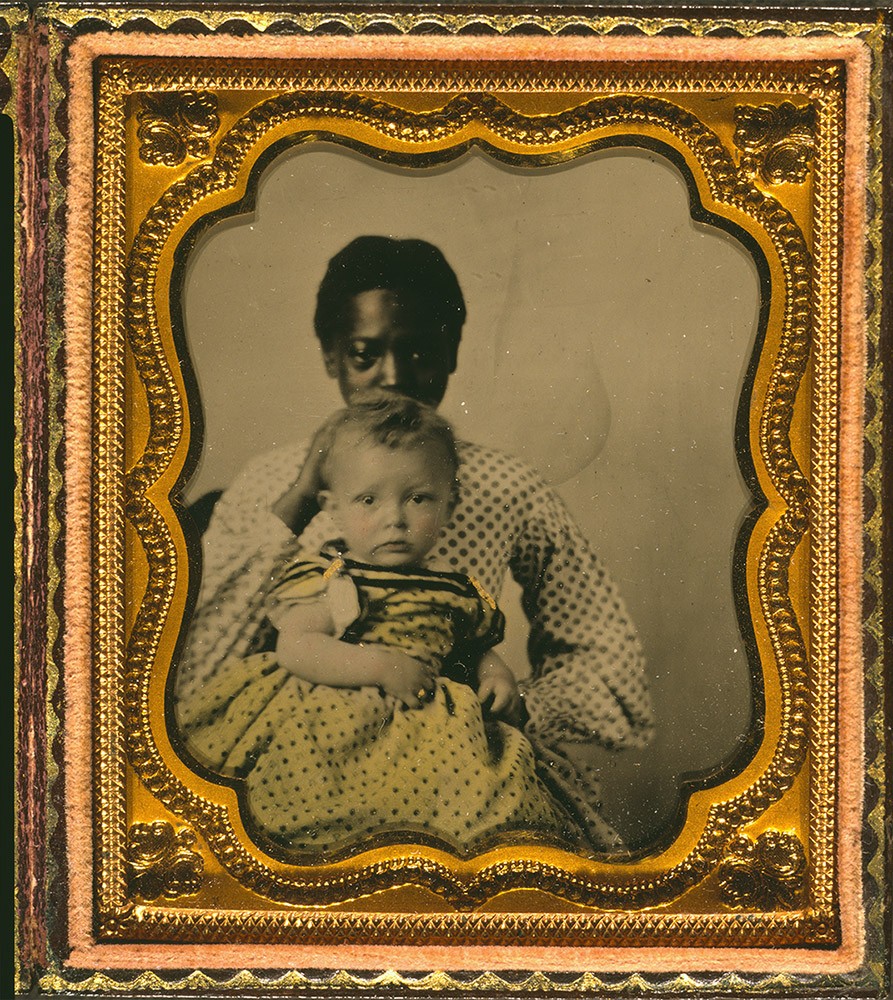

Although antebellum artwork often marginalized them, I strive to put enslaved individuals at the center of this project. Because the institution of slavery attempted to strip away their humanity, using artistic resources (especially those made during the antebellum period and often by their oppressors) to recover human lives and experiences proves problematic. Abolitionist art tended to stunt enslaved people’s agency by focusing on the violence enacted upon them. Pro-slavery art is, by contrast, almost always a farce. Despite this, I continue to work to locate the buried individual through various research means, which often involves reading between the lines (or brushstrokes), parsing the words of enslavers, and embracing unknowns. I also draw parallels between the cover-up of slavery’s realities and the attempted suppression of enslaved people’s humanity, while also celebrating enslaved people’s own, often concealed, culture and humanity.