Ann C. Huppert

Building Knowledge: The Culture of Construction in 16th-Century Rome

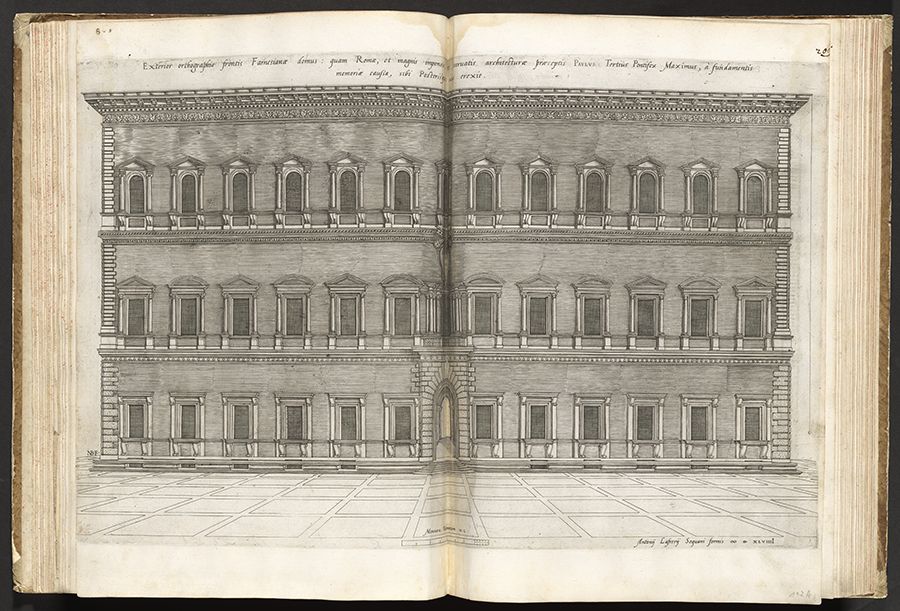

Nicolaus Beatrizet, published by Antonio Lafreri, Palazzo Farnese, 1549, engraving, National Gallery of Art, Washington, The Ahmanson Foundation, 2012.46.1.21

Architecture has always been a collective endeavor, entwining those who envision a design and those who realize it in built form. Yet the dominant narrative, one inherited from Renaissance writers, still privileges the architect as prime mover while downplaying the myriad contributions of others—not only patrons and their agents, but especially builders, craftsmen, and artisans. My book project reconsiders major architectural works of early modern Rome, envisioning the city as a site of networks for the exchange of knowledge about architecture and construction. I focus on mechanisms of communication as the key to understanding this generation of knowledge, redefining architectural authorship and challenging established scholarship, in part by elevating practical knowledge alongside theoretical knowledge, which was long considered solely the purview of the architect.

An alternative story emerges from the work yards of Counter-Reformation Rome, a rapidly rebuilding city. Construction sites formed a nexus for economic, artisanal, and intellectual activities, and the Fabbrica (Building Works) of Saint Peter’s Basilica served as a central generator and repository of knowledge surrounding architecture. The Fabbrica provides a lens through which I examine organizational structures and explore the networks of individuals at work on multiple projects beyond the Vatican, through a series of case studies that includes residential and religious architecture together with urban infrastructure. By tracing communications surrounding the design process, charting the interchange of knowledge between a range of participants, and mapping the physical locations of their exchanges, I seek to narrate a fuller, more nuanced, and inclusive story of 16th-century Renaissance architecture.

During my fellowship, I began my chapter on the Palazzo Farnese, a monument that still dominates Rome’s urban landscape. Nicolaus Beatrizet’s 1549 engraving provides a striking portrait: filling the page, his image suggests a completed building, unencumbered and detached from its surroundings, framed and fixed in space by the carefully rendered perspectival construction of the fronting piazza. The Latin caption at the top highlights the patronage of Pope Paul III. A narrative of its succession of head architects derives from another vital period source, The Lives of the Artists by Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574): Antonio da Sangallo (1483–1546) led the project for over four decades, beginning in 1513, followed at his death by Michelangelo (1475–1564), Jacopo da Vignola (1507–1573), and ending with Giacomo della Porta (1532/1533–1602 or 1604), who oversaw the completion of the rear portions of the palace only in 1589.

Anonymous, Palazzo Farnese under construction, c. 1541, drawing, Biblioteca Nazionale di Napoli, Ms. D.XII.1, c. 8ra. By permission of the Ministero della cultura - Biblioteca Nazionale di Napoli

Vasari, in his quest to celebrate and elevate the architect’s role as designer, gave little attention to other contributors crucial to the realization of architectural projects. We gain a sense of some of these figures from a compelling drawing that shows the palace work site, probably around 1541. While architecture predominates, with new construction enveloping a preexisting towered palace, it is the stoneworkers, masons, and laborers—along with their cranes, scaffolding, carts, horses, and tools—who animate the view. The drawing exemplifies the collective engagement in the realization of buildings that is the focus of my investigation.

My two months at the Center were highly productive, providing focused time to assess my primary source materials and write with ready access to fundamental library resources, while also benefiting from invaluable exchanges with colleagues. Architectural drawings together with financial accounts and other project records preserve evidence of how design information was conveyed and elucidate collaborations between participants on the project. The rich repository of images in the National Gallery’s Italian Architectural Drawings Photograph Collection (assembled under the direction of Henry A. Millon) and the opportunity to study engravings in two volumes of Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae further advanced my research. Within the surviving documents, I now have identified recurring names of individuals beyond the well-known architects, thereby establishing continuity of project supervisors and master craftsmen even as the chief designers changed, and I have outlined the organizational structure at the Palazzo Farnese work site as compared with other projects in the city. Building on my continuing research into the construction of Saint Peter’s Basilica, the Church of the Gesù, and Santa Maria in Traspontina, I can chart interconnections that span across building sites. My research therefore points to the significant roles of multiple individuals whose contributions have previously been downplayed in the scholarship on these important buildings.

University of Washington

Ailsa Mellon Bruce Visiting Senior Fellow, fall 2022

Ann C. Huppert returned to the University of Washington, where she is associate professor in the Department of Architecture.