Carol McMichael Reese

Race, Housing, and Community Design in the Company Towns of the US Canal Zone, 1920–1970

For almost a century (1904–1999), the United States governed the Panama Canal Zone as a colonial dominion inside the Republic of Panama, holding sovereign rights over the roughly 50-mile-long, 10-mile-wide swath of territory established by the 1903 Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty. Much of the zone was unbuilt and existed as tropical forest, providing a watershed that insured the canal’s operation and replenishing the flow of water through its locks. But within this lush landscape, a coordinated and highly productive system of civilian communities and military bases was established to house and support those who first built the canal and later administered, serviced, and defended it. As a geopolitical enterprise, the Panama Canal, which opened to traffic in 1914, had global resonance. Its building, operation, and maintenance produced millions of documents—both textual and visual—that were carefully organized and archived from the beginning of the 20th century until the United States released the canal’s operation to Panama on January 31, 1999. My work with these documents, which are housed in the National Archives, has been ongoing since 2002; it has focused on the socio-spatial design of civilian and military communities in the Canal Zone and its relationship to issues of 20th-century urbanization in the United States, Panama, and Latin America more broadly.

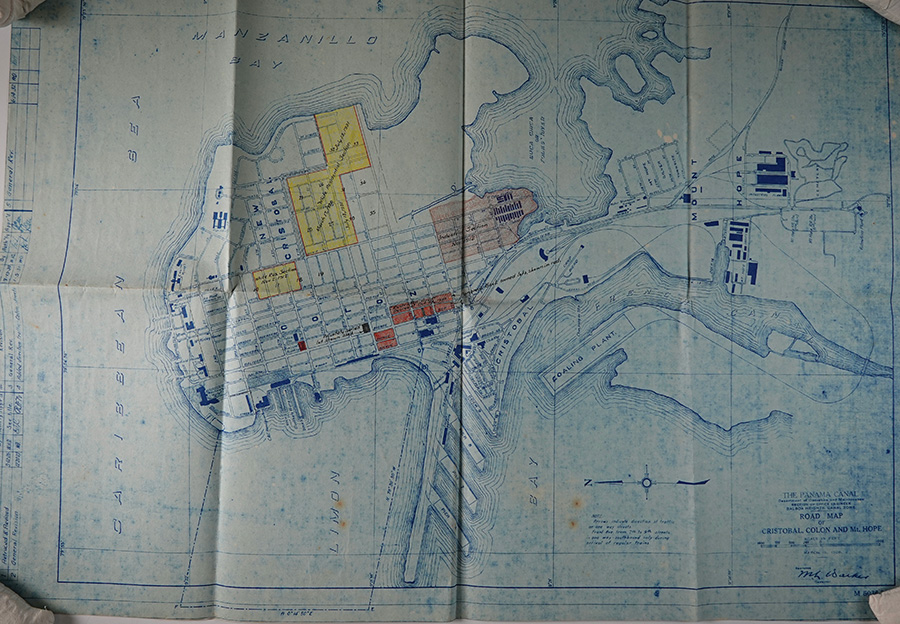

M. L. Walker, Road Map of Cristobal, Colon and Mt. Hope (showing “white residential section” in yellow), March 15, 1926, hand-colored blueprint, National Archives and Records Administration, Archives II, Record Group 185, Textual Records Division

The United States exercised absolute control in the zone from its “tropical” capital of Balboa, which served as the administrative center for the canal’s belt of specialized labor camps, industrial facilities, supply divisions, town sites, and military reservations. These installations evolved to meet the changing industrial, economic, and political conditions of the canal’s operation; bilateral agreements between the United States and Panama; and multilateral international affairs. Initially planned according to prevailing Jim Crow racist ideologies, the zone’s communities have received scant study, yet their architectural and social history yields important new knowledge about the US government’s sanction of racial segregation, its reification in terms of community design, and the ensuing urban effects in neighboring Panama.

The Canal Zone was a territory in which international politics, labor relations, racial constructs, and ecological interdependencies created a fraught field of urban development. Confrontations between Panama and the United States, where the imbalance of power was an omnipresent issue, had important urbanistic consequences in both domains. For the United States, the zone provided a space to test sanitation measures, building materials, supply chain rationales, pre-built and portable structures, tropical landscapes, architectural adaptations for hot and humid climates, and, not least, planned communities with concomitant social and racial hierarchies. In Panama—a nation created in 1903 by treaty in conjunction with the US purchase of assets from the failed French canal project—the expression of modern nationhood through civic architecture and urban planning became paramount. These projects were undertaken as xenophobia in Panama mounted, stimulated not only by the tensions of US occupation, but also by the largely unwelcome presence of Black, predominantly Caribbean, canal laborers. Their status was constantly in flux, as the United States took responsibility for their welfare only so long as they were in canal employ. Shifting labor demands in the zone led to marked demographic and urban change in the Panamanian cities at either end of the canal, Panamá and Colón, where unemployed workers relocated to find jobs and housing, and pressured the Panamanian government for the rights of citizenship. Thus, relationships between the United States and Panama were both symbiotic and antagonistic, exacerbated by nationalist sentiments on both sides of the zone’s mostly unfenced borders.

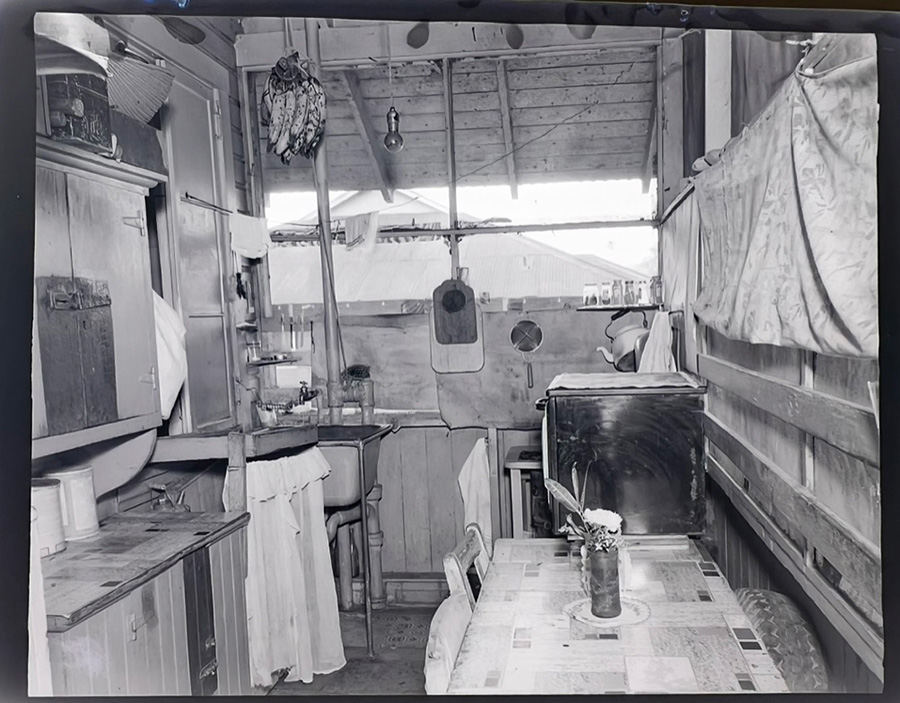

Unknown photographer, House 515, Apartment A, Old Type 18, 12 Single-family Apartments, Red Tank (kitchen in a designated Black community of the Panama Canal Zone), January 11, 1944, black-and-white photograph, National Archives and Records Administration, Archives II, Record Group 185, Still Pictures Division

My research has parsed the Canal Zone’s history in three eras. In 2013, with my coauthor Thomas Ford Reese, I published El Canal de Panamá y su legado arquitectónico (1905–1920) / The Panama Canal and Its Architectural Legacy (1905–1920), a bilingual volume regarding the first period of the zone’s development. My recent fellowship at the Center enabled me to return to the National Archives to seek carefully targeted documents related to key hypotheses concerning two subsequent eras of the urban development of the Canal Zone, which are the subject of our new book. In this well-advanced manuscript, we study the interwar period from the early 1920s to the early 1940s—when the economic effects of the Depression reduced appropriations for the canal and political conflict escalated during Arnulfo Arias’s presidency—and the ensuing period of growth and prosperity from the early 1940s through the 1960s, when the facilities of the zone were mobilized to respond to the United States’ entry into World War II and its operating entities were reorganized.

While in Washington, I found seminal reports on improvements in Canal Zone housing authored by US advisors working in Latin America in the 1940s. These reports and related interventions include critical documents prepared by Jacob Leslie Crane (1892–1988) and Wallace Gleed Teare (1897–1989), advisors to the Federal Public Housing Authority, such as their “Housing Program for the Panama Canal” (1945), which provided design solutions for upgrading the housing of the canal’s Black laborers. These men, as well as other international consultants, worked with federal development agencies in the United States as well as Panamanian and other Latin American colleagues to support housing initiatives and sanitary urban improvements in the zone and elsewhere in the Americas. Their reports evidence international concerns about minimal standards for urban housing, health, and safety, moving concepts of urbanization in the direction of equity. In Washington, I found additional documents concerning the attitudes toward racial segregation in the US armed services that were impactful in the Canal Zone. From the earliest years of canal construction, the planning and building of military and civilian communities in the zone were closely interconnected. These newly consulted documents now allow me to connect the post–World War II integration of US military forces, the proliferation of military family housing in the zone after 1945, and the gradual dismantling of the racist Jim Crow protocols on which the Canal Zone communities were founded.

Tulane University

Ailsa Mellon Bruce Visiting Senior Fellow, summer 2022

Carol McMichael Reese will return to the Tulane School of Architecture, where she is the Favrot IV Professor. In the school, she teaches architectural history and theory, urban studies, and social science research methodology. In Tulane’s School of Liberal Arts, she codirects the Urban Studies minor program.