Kiki Karoglou

MANIA: Narratives of Madness in Classical Art

My current research forms the basis for my next book project on narratives of madness in classical art and their afterlives. Whereas representations of disabled bodies in the ancient Mediterranean world have been examined in scholarly literature, cognitive disabilities and atypical psychologies have not received adequate historical consideration. Addressing this inattention to cultural constructions of “able-mindedness” and their visual representations is a significant aspect of my research, which lies at the intersection of art history, classics, and disability studies.

Clytemnestra Tries to Awake the Sleeping Erinyes (detail), 380–370 BCE, Apulian red-figure bell krater, Musée du Louvre, Cp710. Photo: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Klytaimnestra_Erinyes_Louvre_Cp710.jpg

My study provides insight into how madness was visualized in antiquity and how depictions evolved over time in accordance with various artistic traditions and stylistic developments. It enriches our understanding of not only period attitudes toward madness and insanity but also their wider historical and cultural ramifications reflected in current popular notions of mania and melancholia.

Given the centrality of madness in ancient Greek myth and culture, it has received surprisingly scant attention—especially in English. In classics, scholarly treatments of madness rely almost exclusively on textual evidence, which consists mainly of Homeric epic, Athenian tragedy and comedy, and the Hippocratic corpus. Ainsworth O’Brien-Moore’s Madness in Ancient Literature (1924), for example, provides a solid examination of available literary sources but offers an outdated approach. E. R. Dodds’s seminal book The Greeks and the Irrational (1951), concerning the different iterations of divine mania, has shaped the discussion but, similarly, does not include any visual evidence. Finally, Ruth Padel’s insightful and wide-ranging work focuses exclusively on literature, especially Athenian tragedy, with an eye to psychoanalytic practice.

One reason for the lack of attention to the depiction of troubled mental states and inner psychological conflict is that they are notoriously difficult to render by pictorial means alone. Such depictions typically depend on narrative—that is, tales of temporary insanity, melancholia, and mental distress. There are numerous myths of vengeful gods driving individuals into madness that leads to violence with grim consequences, such as the infanticides committed by Herakles and Athamas or the suicide of Ajax.

The core questions that I examine are: How do artists visualize this complex psychological phenomenon? What are the components of the visual language of madness? To what extent do these visual representations deviate from myths and plays?

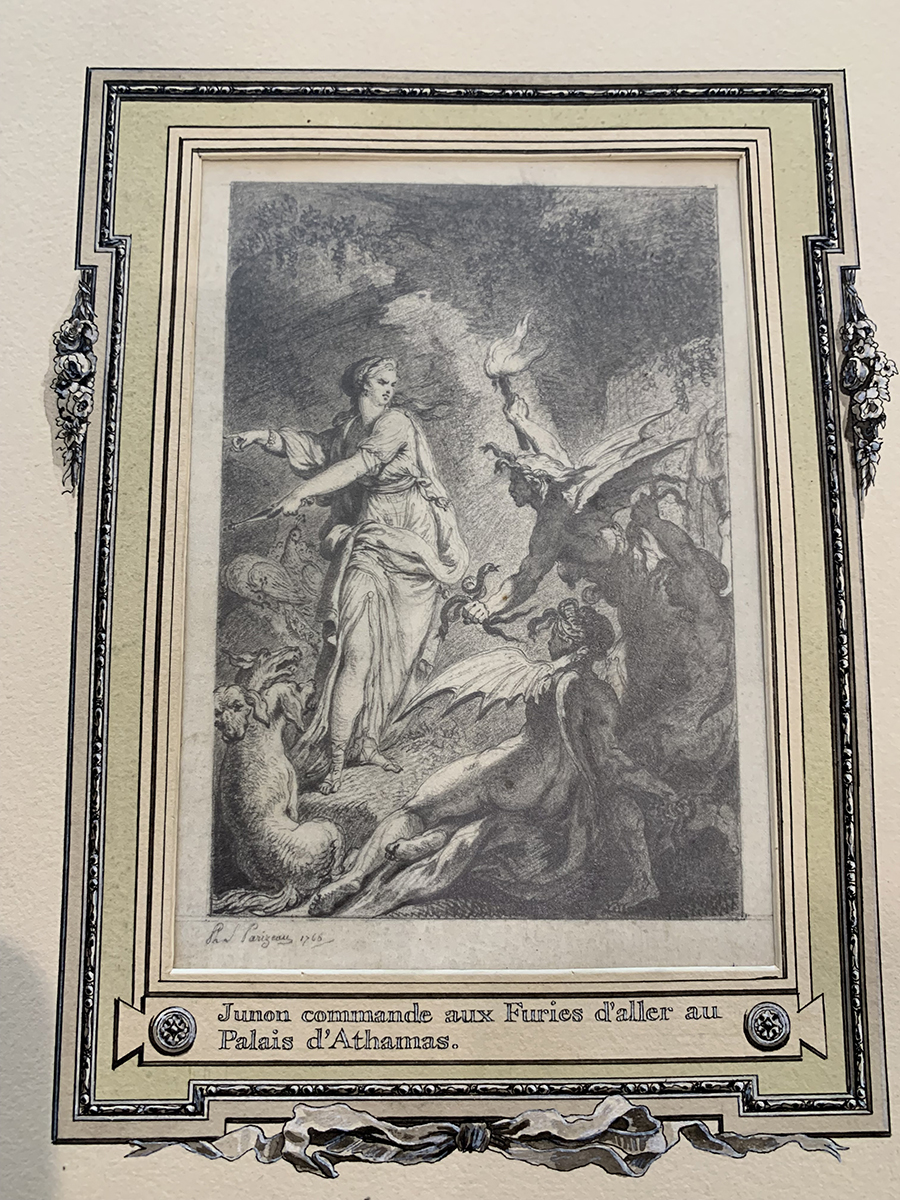

Philippe Louis Parizeau, Junon commande aux Furies d’aller au Palais d’Athamas, 1766, graphite drawing, part of an album for Book IV of Les Métamorphoses d’Ovide, National Gallery of Art, Widener Collection, 1942.9.936. Photo: Kiki Karoglou

Pictorial narratives portray madness though acts of violence and murder. Painters distinguish these manic episodes from violence in the battlefield or cold-blooded crimes by using visual markers of disassociation. These might include the epiphany of the god who causes madness, such as Dionysus, or the personification of the maddening agent, such as Mania (mad rage), Lyssa (rabid frenzy), or the Erinyes (Furies), the embodiment of hereditary guilt. Another visual tool involves distorted poses and frantic gestures that signify the intense emotions of both the inflicted and the spectators, such as the grief and horrified disbelief of onlookers.

Structurally, the book presents specific madness narratives as case studies. A brief discussion of literary sources and other ancient testimonia is followed by an in-depth analysis of visual evidence—for example, Athenian and South Italian red-figure vases, Roman mosaics and wall paintings, as well as 16th- to 18th-century prints, drawings, and panel paintings.

During my fellowship, I further explored some of the material in question and focused on postclassical representations of myths involving madness. These comprise primarily Flemish, Italian, and French book illustrations (engravings and prints) of Ovid’s Metamorphoses. To this end, I examined firsthand various editions in the National Gallery’s collection, such as Philippe Louis Parizeau’s drawing of an episode of the madness of King Athamas, illustrated here.

In addition to thinking through these ideas as well as interacting with the Center’s scholarly community in residence, my fellowship enabled me to explore new research directions, as, for example, the gendering and coloring of madness, to further develop and define the book’s chapter structure and intended audience.

New York, NY

Ailsa Mellon Bruce Visiting Senior Fellow, fall 2022

Kiki Karoglou will continue her research and writing to complete her manuscript as an affiliated scholar at the Center for Research in the Humanities, New York Public Library.