Rheagan Eric Martin

Printed, Painted, and Illuminated: Venetian Visual Culture at the Dawn of Print (1469–1517)

Titian, Madonna di Ca’ Pesaro (detail), 1519–1526, oil on canvas, 478 × 266.5 cm, Basilica of Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, Venice. Photo: Rheagan Eric Martin, with permission of the Ufficio Beni Culturali, Curia Patriarcale di Venezia

Located in the Franciscan Basilica of Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari in Venice is an altarpiece painted by Titian known as the Madonna di Ca’ Pesaro (1519–1526). Often lauded for its intriguing organization of space, the painting places the Madonna at an oblique angle to the picture plane. More significantly for my study, what appears to be a printed book is located at the center of the composition in the hands of Saint Peter. The saint’s index finger points to a four-line-high indentation in the text—an intriguing gap of white paper at the center of a major altarpiece. It would be quite rare for a manuscript, usually adorned through illumination, to contain an empty space; however, it was extremely common for publishers of incunabula to leave a large blank space with a small printed initial at the center for later customization.

This choice on Titian’s part points to the status of the printed book in Venice at the turn of the 16th century: contrary to the perception of print as inferior to manuscript predecessors, the printed book held particular significance for the painter, the patron, and the city in terms of its spiritual, political, and material functions. Furthermore, the anachronistic pairing of an early Christian saint with a printed book emphasizes a moment in which the technology of movable type prompted image-makers and viewers in Venice to reconsider critical aspects of visual culture and representation. A printed book at the center of a major commission referenced Venice’s position as the most productive center of European printing by the first quarter of the 16th century, producing an estimated 70 percent of all European books.

The first year of my Samuel H. Kress Predoctoral Dissertation Fellowship allowed me to consult Venetian incunabula firsthand in collections throughout the UK, Germany, and Italy. Through visual analysis of fonts, paper quality, ink quality, watermarks, woodblock illustrations, hand coloring, rubrication, illumination, and historic bindings, my interests coalesced around certain categories of printed books in which publishers developed sophisticated solutions to the technological challenges within specialized fields of knowledge. Each chapter of my dissertation, which I finalized during my time at the Center and will defend in summer 2023, focuses on different categories of knowledge: classical and legal texts, geometric and astronomical treatises, and liturgical works often containing printed music and woodblock illustrations. Although every solution was unique to its task, each also demonstrated a self-awareness of the technology of printing with movable type in dialogue with broader visual and material culture.

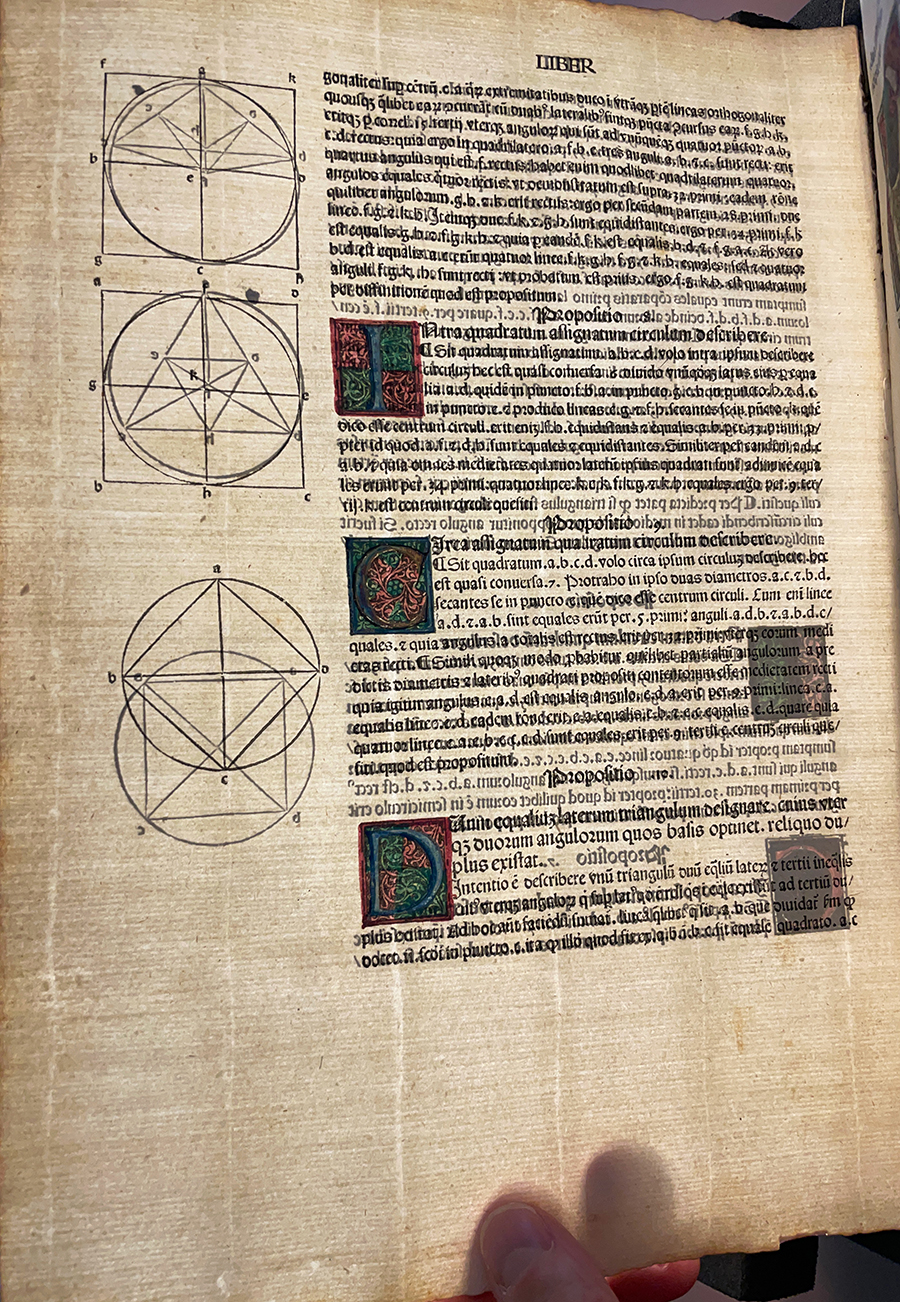

Euclid, Elementa geometria, trans. Adelard of Bath (1160 CE), ed. Giovanni Campano, published by Erhard Ratdolt in Venice on May 25, 1482, John Davis Batchelder Collection, Library of Congress, Incun. 1482 .E8616 QA22. Photo: Rheagan Eric Martin

The first chapter explores the output of French émigré printer Nicolas Jenson, whose classical histories and legal commentaries represent a moment of transformation as illumination encountered printed word. I consider the “torn-parchment” illuminations, which often adorn presentation copies given to Jenson’s financial investors. The myriad visual relationships made possible by feigned torn parchment influenced later illusionistic frames and layers of representation, including paintings by Giovanni Bellini and Antonello da Messina. I then consider how these illuminations frame the texts through classical technologies of reproduction, including depictions of wax seals, signet rings, and intaglio gems. The conspicuous presence of these representations of reproductive technologies made visual claims about the accuracy and correctness of the printed word at the threshold of encounter with the text.

Next, I consider the work of German expatriate Erhard Ratdolt. The second chapter analyzes Ratdolt’s mathematical and astronomical publications. I argue that Ratdolt utilized the precise registration of the printing press to align diagrams on either side of a single folio. In the course of turning the page, transmitted light passing through the translucent folio causes both diagrams to become visible simultaneously, allowing for comparison. Beyond book production, translucency and unexpected shifts in opacity were also present in other emerging visual technologies in Venice, including the production of clear glass and oil paint.

The final chapter analyzes works created by Lucantonio Giunti and Johann Emerich containing printed musical notation. The gradual published from 1499 to 1501 under Giunti’s aegis was the largest incunable ever created and the first to contain woodblock illustration in addition to printed musical notation. The corpus of woodblocks appearing in the gradual was reused for more than 30 years in a variety of liturgical texts. I draw upon Franchino Gaffurio’s proportional music theory to argue for the possibility that Johann Emerich may have conceived of woodblocks that would function on the proportional scale of the folded folio. Throughout these categories, my dissertation elucidates a dynamic, reciprocal relationship between the technological advancements of print and broader artistic production in Venice and the Veneto.

University of Michigan

Samuel H. Kress Fellow, 2021–2023

Rheagan Eric Martin has accepted a position at the Library of Congress, focusing on digital projects and accessibility.