Romare Bearden was born on September 2, 1911, in Charlotte, North Carolina. His parents, Bessye Johnson Banks Bearden and Richard Howard Bearden, moved the family north to New York City when Romare was about three years old, leaving family and friends in the rural South, as did many African Americans during the first wave of what is now known as the Great Migration. All shared in the hope of creating a better life in the urban North.

Bearden grew up in Harlem, but returned frequently to Charlotte during his boyhood to visit paternal relatives. He also spent time with his maternal grandmother in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where he completed his final two years of high school. His childhood memories, marked by the distinct character of his experiences in these three cities, would eventually play a central role in his art. Bearden’s father worked for the railroad and later as an inspector for New York City’s sanitation department. Bessye Bearden was the New York editor for the Chicago Defender, a weekly African American newspaper, and was active in public service and in politics. Her wide social circle meant that the Bearden’s Harlem home was frequented by leading African American intellectuals, writers, and musicians, including W.E.B. Du Bois, Langston Hughes, and Duke Ellington. This rich cultural environment shaped Bearden’s early life in Harlem and informed his art.

Bearden graduated from New York University in 1935 with a degree in education. He took a job as a case worker for New York City's social services, where he would continue to work for 34 years, and attended night classes at the Art Students League. During the 1930s he was also a political cartoonist, his work appearing in The Crisis, the Baltimore African-American, and other publications.

In 1940 Bearden had his first one-man exhibition of paintings and drawings. With the onset of World War II, he served in the U.S. Army (1942–1945) and in 1950 he traveled to Paris on the G.I. Bill. He returned to the United States, and between 1951 and 1954 he turned briefly to songwriting. His most acclaimed hit was "Seabreeze," co-written with Fred Norman and Laerteas (Larry) Douglas. In September of 1954 he married Nanette Rohan.

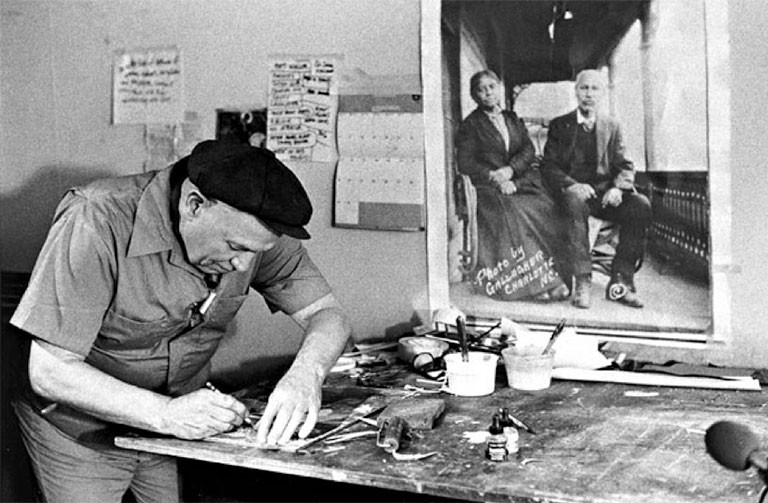

During the 1940s and 1950s Bearden explored artistic styles from social realism to abstract expressionism. But it was in the 1960s, partly out of his involvement with the artists' group Spiral, that he discovered the power of the collage technique and established his mature style. Enlarged black-and-white photostats of his collages, which he named Projections, were first exhibited in 1964 and met with critical acclaim. By 1966 his success was enough to allow him to reduce his caseworker hours, and by 1969 he retired fully from social services to dedicate himself to his art. After 1964 Bearden made no additional Projections, but during the 1970s and 1980s he added large-scale murals, tapestries, and set and costume design to his repertoire. He also produced numerous monotypes and prints in addition to his signature collages.