In 1969 a group of Hungarian directors, screenwriters, and cinematographers signed a petition that would introduce the new direction of documentary filmmaking in the subsequent decade, marked by the increasing importance of social research in determining both the production frameworks and content of films produced at BBS.[1] Long Distance Runner can be understood as an indicator of this shift, illustrating the clear transition from the lyrical film style of the early 1960s to a more direct, probing, and critical approach that defined nonfiction filmmaking in the 1970s.

Banner stills L to R: Long Distance Runner, Four Bagatelles, and New Year's Eve, all courtesy MaNDA Archive

Long Distance Runner and New Year's Eve

Long Distance Runner (Hosszú futásodra mindig számíthatunk)

Gyula Gazdag, Hungary, 1968, 35 mm transfer to digiBeta, 13 minutes 12 seconds

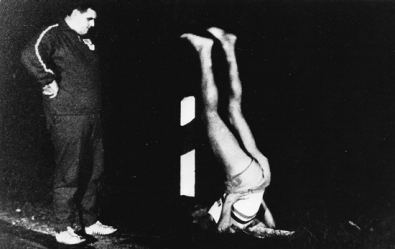

Still from Long Distance Runner, courtesy MaNDA Archive

Still from Long Distance Runner, courtesy MaNDA Archive

Considered an important early example of Hungarian cinéma vérité, this deceptively simple film focuses on György Schirilla, a cab driver who famously ran marathons in celebration of socialism in the 1960s, including a run from Budapest to Moscow that lasted 32 days. The film documents an event held in honor of the athlete in the rural town of Kenderes that culminates in an opening ceremony for a roadside café to be named after him. Despite the highly publicized event, a decree prohibiting establishments from being named after living persons forces the the naming ceremony to be downgraded to a clumsy celebration of Schirilla’s efforts and the opening of a rather unremarkable sports bisztro. While sympathetically portraying the runner as an uncomplicated, soft-spoken, and disciplined man focused on his physical performance and acts of endurance, Gyula Gazdag’s (b. 1947) camera and microphone seek out the fumbling and self-important party officials in charge of the event.[2] In this way, the clueless participants captured in the film unwittingly expose the inherent absurdities and contradictions of the rituals of state-prescribed socialist propaganda, revealing what fellow filmmaker Gábor Bódy, in discussing this film, perceptively called the “cult of pseudo-achievements.”[3] — Sonja Simonyi

With thanks to Sebestyén Kodolányi at the Balázs Béla Stúdió Archive and Dorottya Szörényi at the Hungarian National Digital Archive and Film Institute (Magyar Nemzeti Digitális Archívum és Filmintézet [MaNDA]) for their assistance with research and help in making the screening of this film possible in Washington.

New Year’s Eve (Szilveszter)

Elemér Ragályi, Hungary, 1974, 35 mm transfer to digiBeta, 15 minutes 29 seconds

Still from New Year's Eve, courtesy MaNDA Archive

Elemér Ragályi (b. 1939) is a prolific cinematographer of postwar Hungarian film who lensed the films of numerous fellow BBS members from the 1970s onward—including those of Gyula Gazdag, György Szomjas, Judit Elek, and Pál Sándor—working on a diverse list of fiction and documentary works. This experimental documentary, which Ragályi directed, keenly observes the chaotic goings-on of a wide range of people during New Year’s Eve festivities in Budapest. Presenting a satirical view of a cross-section of socialist Hungarian society and a critical look on its stale cultural output, the film shows trite forms of popular entertainment ranging from dance revues to operettas, the footage occasionally sped up to enhance the unnatural gestures and mannerisms of performers, humorously transforming their acts into slapstick comedy. These images alternate with shots of crowds of ordinary citizens caught in a drunken haze, exposing the near hysteria generated by this mass celebration and the widespread aggression lying underneath forced social conventions.

Still from New Year's Eve, courtesy MaNDA Archive

The film shifts from the city streets to numerous bars and restaurants, where people repeatedly perform for the camera (or stare self-consciously into it), and to the nearly empty streets of early morning, showing the aftermath of the celebrations. Also captured are the mediated images of TV screens broadcasting the state television’s official evening program. The juxtaposition of these elements highlights the apparent connections of the events, yet an undeniable sense of disaffection pervades the night of partying. More than a captivating take on a near-universal day of feasting, New Year’s Eve offers a rich portrait of Hungarian urban society in the mid-1970s. The experimental score enhances the film’s visual world with an intricately textured soundscape that merges the aural abstraction of electronic music with prerecorded sounds (audiences clapping, celebratory horns blaring), adding these elements disjointedly to the film’s montage of images. In addition, Ragályi incorporates fragments of popular tunes, including a German song performed by Zarah Leander, an iconic 1930s actress.[4]

Still from New Year's Eve, courtesy MaNDA Archive

Along with this creative merging of sound and image to express the theme of alienation, the film appropriates the general tropes of the city film, a genre of nonfiction cinema that emerged in the early 20th century. This is particularly evident in the film’s continuous move through Budapest’s diverse neighborhoods and social circles and progression from late evening to early morning. — Sonja Simonyi

With thanks to Sebestyén Kodolányi at the Balázs Béla Stúdió Archive and Dorottya Szörényi at the Hungarian National Digital Archive and Film Institute (Magyar Nemzeti Digitális Archívum és Filmintézet [MaNDA]) for their assistance with research and help in making the screening of this film possible in Washington.

1. “Szociológiai filmcsoportot!” [A sociological film group!], Filmkultúra 3 (1969). (back to top)

2. The original title of the film references a nonsensical poem read by one such official, who, in greeting Schirilla on his entry into Kenderes, states: “May we always count on your long running.” (back to top)

3. Gábor Bódy, “A fiatal magyar film útjai” [The roads of young Hungarian film] (1977), reprinted in Bódy Gábor: egybegyűjtött filmművészeti írások [Bódy Gábor: Collected writings on film], ed. Vince Zalán (Budapest, 2006), 113. (back to top)

4. The song in question, “Und dann tanz ich einen Czardas” (And then I dance a csardas) is a smarmy schlager that references Hungary as an exotic realm of passion, romance, and the popular dance called csárdás. Aurally evoking fascist-era popular culture, it is yet another irreverent element in the film, implicitly connecting different iterations of low-brow cultural expression across two diverging political eras. (back to top)