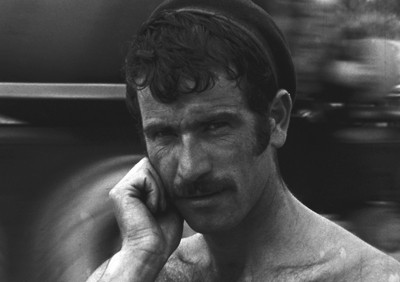

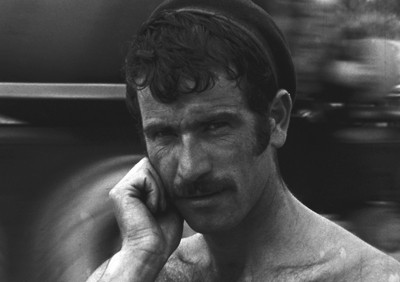

Banner stills L to R: Encounters, courtesy Croatian Film Association;

Anthony's Broken Mirror and Vowels, courtesy Alternative Film Archive, Academic Film Center, Belgrade

Still from Encounters, courtesy Croatian Film Association

In the 1960s, Yugoslavia—which had broken away from Soviet influence in 1948 and strove to remain non-aligned amid the polarization of the Cold War—became a place where artistic experimentalism took many forms, often receiving official support, though never becoming mainstream. The Croatian capital of Zagreb offers an example of a particularly vibrant cultural scene. In 1961, it hosted the first of a series of international New Tendencies exhibitions, which promoted such phenomena as concrete, neo-constructivist, kinetic, and conceptual art. The impact of these exhibitions was amplified even further through the publication between 1968 and 1973 of the multilingual journal Bit International. The first edition of the avant-garde Music Biennale Zagreb took place in 1961, introducing local audiences to contemporary music from around the world, most notably jazz. Even earlier, in 1955, the International Graphic Biennial was established in the Slovene capital of Ljubljana. Further major cultural events established in Yugoslavia in the 1960s to open up the country to international cultural trends included the BITEF international experimental theater festival and the FEST international film festival, both held in Belgrade.[1] In addition to this, the cinematheques in major cities, such as Belgrade, Zagreb, and Ljubljana, regularly screened films from influential contemporary movements, such as Italian Neorealism and the French New Wave.

Against this background, film experimentation also thrived, thanks largely to an extensive network of amateur film clubs that were established in numerous cities to allow non-professional film enthusiasts to find each other and gain access to necessary equipment. In the 1950s and 1960s, these clubs attracted many talented amateurs; some of Yugoslavia’s most acclaimed filmmakers of the era—including Dušan Makavejev, Želimir Žilnik, and Karpo Godina —became professionals after having made films as members of amateur clubs. The clubs remained a viable path into professional filmmaking until the end of the socialist era. In subsequent decades, less well known filmmakers, including Milan Šamec, Nikola Đurić, and Igor Toholj, turned their involvement with film clubs in Zagreb and Belgrade into lifelong careers lasting into the post-socialist period.

Still from Vowels, courtesy Alternative Film Archive, Academic Film Center, Belgrade

Most members of amateur film clubs, including visual artists who wanted to experiment with film, never became professionals but still produced remarkably adventurous short films. Their story, however, remains much less known. As Jurij Meden and others writing in the Journal of Film Preservation have noted, experimental cinema in Yugoslavia both flourished and, at the same time, was erased from the historical record precisely because “experimental film almost unfailingly originated in the tradition of the so-called amateur film, whose home ground was the numerous cinema clubs . . . in all the major cities of the former federation."[2] Fortunately, in recent years, several exhibitions and accompanying books have worked to recover the multifaceted history of amateur experimentalism in Yugoslavia. The 2010 edition of the Belgrade Alternative Film Festival was dedicated to The Cine-Club Era, resulting in a publication of the same name.[3] Publications that have come out since then include This Is All Film (2010–11); As Soon As I Open My Eyes I See a Film (2011); and Cinema by Other Means (2012).[4]

A key protagonist of these histories is the Genre Experimental Film Festival (GEFF), which was hosted in Zagreb four times between 1963 and 1970 and which introduced during its first iteration the influential concept of “anti-film,” discussed below in connection to its main theorist, Mihovil Pansini. Most of the films by Croatian filmmakers shown in the present program (with the notable exception of Ivan Marinac’s Acceleration) represent the concrete cinema that came to be associated with GEFF and “anti-film.” By contrast, the contemporaneous activities in the late 1950s and 1960s of filmmakers in Belgrade, which also had a sizable and active amateur filmmaker community, were focused almost exclusively on making narrative “alternative” films, often with symbolist and surrealist overtones and political messages, which shifted from covert to overt as the 1960s wore on. These are represented here by Dušan Makavejev’s early work from the 1950s, in which one can easily see the seeds of his Black Wave sensibilities.

Still from Anthony's Broken Mirror, courtesy Alternative Film Archive,

Academic Film Center, Belgrade

In the early 1970s, when Marshal Tito’s government cracked down on dissent following the political turmoil of the late 1960s, Serbian filmmakers bore the brunt of official prohibitions and persecutions, as detailed in the 2007 documentary Censored without Censorship (Zabranjeni bez zabrane).[5] Yet the crackdown had a chilling effect on culture more broadly, and the Yugoslav experimental film scene did not see such another powerful outburst of iconoclastic creativity again. The activites of amateur film clubs, however, did continue, and provocative works on film, such as Neša Paripović’s N.P. 1977 (1977) also came out of the circle of young artists artists that gathered around the Student Cultural Center, founded in Belgrade in 1971. In addition to Paripović, other members of this circle included Raša Todosijević and Marina Abramović.

In the mid-1970s, the new medium of video also attracted a different group of experimenters, many of them artists. The video works by Ivan Ladislav Galeta and Sanja Iveković screened in this program, as well as those by Dalibor Martinis and and Goran Trbuljak screened in the Medium Experiments program, represent the emergence of this first generation of Yugoslav experimental video makers, some of whom—notably Iveković and Martinis—combined a desire to produce cultural critiques with explorations of the nature of video as a medium. — Ksenya Gurshtein

1. For more on this, see Barbara Borčić, “Video Art from Conceptualism to Postmodernism,” in Impossible Histories: Historical Avant-Gardes, Neo-Avant-Gardes, and Post-Avant-Gardes in Yugoslavia, 1918–1991, ed. Dubravka Djurić and Miško Šuvaković (Cambridge, MA, 2003), 493. (back to top)

2. Lorenzo Della Rovere et al., “Behind an Experimental Film Heritage: Preservation and Restoration Protocols and Issues,” Journal of Film Preservation 89 (November 2013): 115. As the authors note, “The line separating amateur film from experimental film is . . . unclear not only because of the subjectivity of the judgment, but also because . . . the former term refers to production conditions, while the latter denotes aspirations, procedures, and effects of a specific cinematic expression.” Ibid., 116. (back to top)

3. Yet more information can be found in Nevena Daković, “The Unfilmable Scenario and Neglected Theory: Yugoslav Avant-Garde Film, 1920–1990,” and Barbara Borčić, “Video Art from Conceptualism to Postmodemism,” both in Impossible Histories: Historical Avant-Gardes, Neo-Avant-Gardes, and Post-Avant-Gardes in Yugoslavia, 1918–1991, ed. Dubravka Djurić and Miško Šuvaković (Cambridge, MA, 2003), 466–89 and 490–524. (back to top)

4. The latter was related to an exhibition, a review of which can be found here. (back to top)

5. According to Lorraine Mortimer, the turmoil of this period came as a result of the official response to antigovernment student demonstrations in 1968 in Belgrade and Ljubljana and “the Croatian nationalist-separatist crisis of 1971. Tito intervened to purge ‘top Croatian party officials who supported nationalist separatist goals,’ and, as ‘a quid pro quo, he supported the campaign in Serbia’ against dissident Marxists, . . . members of the non-Marxist humanist intelligentsia, radical students, and artists.” Lorraine Mortimer, Terror and Joy: The Films of Dušan Makavejev (Minneapolis, 2009), 12. (back to top)