Alina Szapocznikow (1926–1973) was a Polish sculptor whose difficult biography profoundly informed her work.[1] As an adolescent during World War II, she was imprisoned with her Jewish family in ghettos and concentration camps. After the war, she studied sculpture in Prague and Paris, returning to Poland from France in 1951 after being diagnosed with tuberculosis. In Poland, she was widely celebrated as a sculptor, even representing the country at the Venice Biennale. Despite this, she emigrated back to France in 1963. It was there that she made her most renowned works—vulnerable mannequin-like forms and solitary misshapen figures—based on casts of her own body fashioned out of unconventional materials, such as polyester, that captured both the texture of the flesh and its fragility. In a 1971 poem, she contemplated a piece of chewing gum: “Pulling out of my mouth the strangest forms / I suddenly realized / the existence of an extraordinary collection of abstract sculptures, / passing between my teeth.”[2] In 1968, she was diagnosed with breast cancer. She died in France in 1973 at the age of 47.

Banner stills L to R: 10 Minutes Older, courtesy Riga Film Museum; Black Film, courtesy Želimir Žilnik; 235 000 000, courtesy Riga Film Museum

Trace (Ślad)

Helena Włodarczyk, Poland, 1976, digital file from 35 mm, 13 minutes

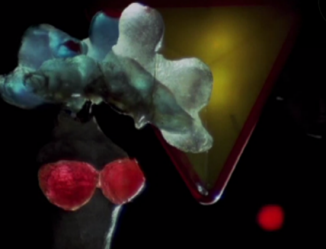

Still from Trace, courtesy Filmoteka Muzeum

Still from Trace, courtesy Filmoteka Muzeum

In 1975, Irena Kolat-Ways organized in Łódź the first posthumous exhibition of Szapocznikow’s work. Inspired by the show, Helena Włodarczyk (b. 1945), then a film student in Łódź with a previous degree in art history, made Trace based on it, with the film being produced by Film Polski in 1976 as part of the series “Contemporary Polish Sculpture” and Kolat-Ways cowriting the script.[3] Trace was, in fact, one of three Polish films about Szapocznikow’s work to be made in the 1960s and 1970s (one of the other two films can be seen here), but it was the only one that tried to echo the artist’s dedication to physicality in her work. The film animates the anthropomorphic forms so that they seem to come alive and amplifies Szpocznikow’s affinity for modern, vernacular materials by placing her sculptures in the real world outside the museum. The intense physicality of Szapocznikow’s work is evoked both literally and metaphorically throughout the film, where the artist is represented in black-and-white still photographs and archival film footage while her voice is articulated through dramatic readings of excerpts from her essays.

Yet these traditional documentary elements are only part of this cinematic portrait: Włodarczyk populates several urban streets with Szapocznikow’s works of art. She films a group of embryo-like forms overhead, swooping elegantly (via cherry picker) from on high down to street level; tracks a large white figure with gnarled hands—lips and nipples painted bright red—through arches and along the sidewalks of Old Town Łódź; and positions the heads of sculpted mannequins along lace-curtained open windows, filming them from street level. The staccato music of Jan Freda montaged with sounds of radio transmissions and static throughout these discursive scenes reveal Włodarczyk’s interest in experimentation and playfulness with her chosen medium. Freda, a member of the Workshop of the Film Form, later went on to a career as a successful sound editor. Notably, the creation of the flim was made possible by the cooperation of the Łódź museum’s director, Ryszard Stanislawski, who had been Szapocznikow’s first husband and who released the sculptures and allowed them to be paraded through the streets.[4] The filmmaker, who is now known by the name Hanka Włodarczyk, received four awards in 1976 for her debut film and went on to have a career as a director of both documentaries and feature films. — Joanna Raczynska and Ksenya Gurshtein

With thanks to Wojciech Bernacki, Wytwórnia Filmów Oświatowych (WFO), Łódź and Łukasz Mojsak, Filmoteka Muzeum, Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw, for making a screening of this film possible in Washington.

10 Minutes Older (Vecāks par 10 minūtēm / Старше на 10 минут)

Herz Frank, Latvia, 1978, 35 mm, 10 minutes

Still from 10 Minutes Older, courtesy Riga Film Museum

The idea behind 10 Minutes Older is deceptively simple: over a single 10-minute take, the widest gamut of emotions—from joy to terror—is mirrored in a face of a little child at a puppet theater show. Yet it is hardly an overstatement to say that this is one of the most influential short films ever made. An astonishing technical feat that also carries a real emotional punch, it brought together Latvia’s most talented documentary filmmakers: Herz Frank (1926–2013) wrote the script and directed the film while the cinematography was done by Juris Podnieks (1950–1992), who later directed such acclaimed documentary features as Is It Easy to Be Young? (1986) and Hello, Do You Hear Us? (1989).

The film’s subtitle is “A Tale about Good and Evil.” This description—ostensibly of the puppet play that the child is watching—also reflects the politics of artistic creation in the Soviet Union. Frank added the subtitle to circumvent omnipresent Soviet censorship, which rejected any hint of “formalism.” By implying a narrative that the censors could understand, Frank snuck past them a piece of reflexive filmmaking with a modernist agenda that also makes viewers reflect on their experience of the film.[5]

Still from 10 Minutes Older, courtesy Riga Film Museum

Herz Frank has said that shooting the film was a magnificent event during which the most crucial thing possible in documentary cinema–touching a human soul—happened by means of the rather crude instrument of a camera.[6] It is exactly such baring of the human soul that has interested Frank in his other groundbreaking work—be it a confession of a man on death row for murder (The Last Judgment, 1987) or a retrospective and provocative look at his own creative and private history in the acclaimed Flashback (2003), a film in which the director’s chest is cut open for heart surgery. Though not as “heavy” in terms of subject matter than the later films, 10 Minutes Older presents a stunningly graphic visual challenge and a powerful metaphor for Frank’s relentless drive to get profoundly close to his subjects.

Inspired by Herz Frank, 15 world-famous directors—including Werner Herzog, Jean-Luc Godard, Wim Wenders, Jim Jarmusch, Aki Kaurismäki, and Bernardo Bertolucci—created their own versions of 10 Minutes Older in Ten Minutes Older: The Trumpet / The Cello (2002). — Līva Pētersone

The series organizers would like to thank Līva Pētersone, curator at the Riga Film Museum, for her tireless assistance with our research for the series. Thanks also to Agnese Surkova and the Latvian Film Centre for help in making a screening of this film possible in Washington.

1. Additional biographical information can be found in Elena Filipovic and Joanna Mytkowska, eds., Alina Szapocznikow: Sculpture Undone, 1955–1972 (New York, 2011). (back to top)

2. Alina Szapocznikow, “One Sunday . . . ,” in Primary Documents: A Sourcebook for Eastern and Central European Art Since the 1950s, ed. Laura Hoptman and Tomáš Pospiszyl (New York, 2002), 199. (back to top)

3. Elena Filipovic and Joanna Mytkowska, eds., Alina Szapocznikow: Sculpture Undone, 1955–1972 (New York, 2011), 45, n. 24, and 135, n. 11. (back to top)

4. Elena Filipovic and Joanna Mytkowska, eds., Alina Szapocznikow: Sculpture Undone, 1955–1972 (New York, 2011), 45, n. 24. (back to top)

5. For a scholarly analysis of the subtitle and its significance, see Inga Pērkone-Redoviča, “Herz Frank and Modernism in Latvian Film,”. For Herz Frank’s account of the addition of the subtitle, see the interview with him first published in the magazine Искусство кино / Iskusstvo kino [The art of cinema], no. 2 (Moscow, 1993), reprinted in Herz Frank, Uz sliekšņa atskaties [Look back at the threshold], trans. Kristīne Matīsa (Riga, 2011). (back to top)

6. Interview with Herz Frank, first published in the magazine Искусство кино / Iskusstvo kino [The art of cinema], no. 2 (Moscow, 1993), reprinted in Herz Frank, Uz sliekšņa atskaties [Look back at the threshold], trans. Kristīne Matīsa (Riga, 2011). (back to top)