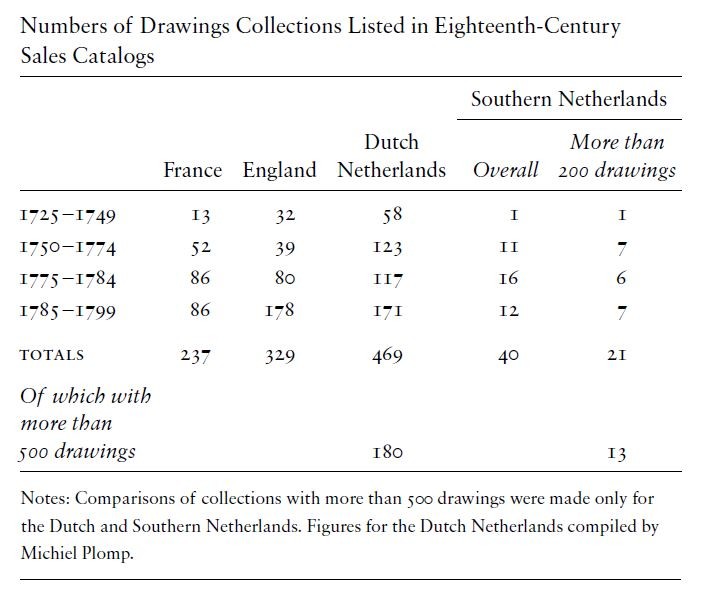

The existence, largely intact, of a collection of more than four thousand Old Master drawings formed in the 1760s is of itself a rare occurrence. That of Count Charles Cobenzl, most of which remains in the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, offers a wealth of material on different fronts. One of very few significant eighteenth-century collections of drawings in the Austrian (Southern) Netherlands, it broadens our understanding of the picture beyond the main artistic centers (for drawings, France, the Dutch Netherlands, and England). This is illustrated by a simple analysis of numbers of drawings collections listed in sales catalogs of the period (see below). Moreover, when Catherine the Great purchased Cobenzl’s collection in 1768, it became, as far as we know, the first of only a handful of drawings collections in Russia in the eighteenth century.

A mass of supplementary information further illuminates contemporary collecting practice: most of the drawings are still on their original mounts, many in the boxes made for them in Brussels, and a manuscript catalog compiled in 1768 records the drawings individually. These boxes and mounts and the notations on them tell us that Cobenzl—based both geographically and culturally between Paris and the Dutch Netherlands—similarly reflected two different traditions in collecting works on paper, moving from a loose-leaf album-based system to the use of stiff mounts and boxes. Changes in the organization of his drawings are also attested in his abundant personal correspondence, which allows us not only to assess the finished collection but also to see how it was assembled over the years. Cobenzl’s letters throw light on the status and social aspects of collecting; they set out his preferences, illustrating his own understanding of individual drawings, of his collection as a whole, and indeed of a “collection” per se. As a noted bibliophile, credited with saving the Royal Library of Burgundy (composed largely of medieval manuscripts and historic texts and formed by the dukes of Burgundy), and founding the Bibliothèque Royale in Brussels as a public institution, Cobenzl seems to have been guided by the idea of the collection as a comprehensive “dictionary” of artists.