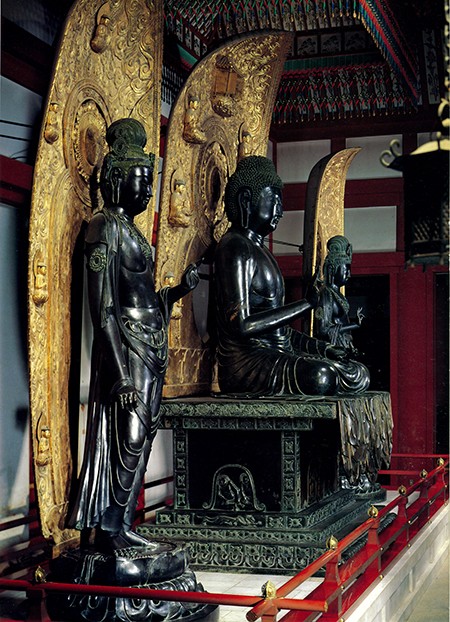

The primary icon at the eighth-century Japanese temple Yakushiji, Nara, is a bronze Buddha more than eight feet tall, seated cross-legged atop a multitiered five-foot pedestal symbolic of the sacred Mount Sumeru. However majestic and rare this colossal sculpture of the early Nara period (710–794), it is the pedestal, with its unusual combination of secular and Buddhist motifs in relief on all four sides, that is unique in Japan’s representational history. For generations of scholars it has been the subject of intense speculation regarding both its provenance and meaning.

When his main consort became sick, the ruler posthumously known

as Emperor Tenmu (r. 672–686) made a vow to build a Buddhist monastery, naming it for the Buddha of Healing, Yakushi Nyorai. Although his consort (posthumously known as Empress Jitō, r. 686–697) recovered, Tenmu himself succumbed to illness. Jitō succeeded Tenmu and completed Yakushiji in the capital, Fujiwarakyō, by around 690. That temple’s main hall housed a seated bronze icon of the Healing Buddha that may have remained in Fujiwarakyō, in this “first” Yakushiji, after the move of the capital to Nara. By 718 the temple’s name was “transferred” to a new monastery in the Nara capital, a practice not uncommon in ancient times. Scholars disagree on whether the triad of a bronze Buddha and two attendant bodhisattvas made for the earlier Yakushiji in Fujiwarakyō was physically moved to Nara or whether it was made anew for the relocated Yakushiji. The style and casting of the triad, in my opinion, indicate the latter, and documented ritual activity suggests a completion date in the 720s. On the basis of the figures and design motifs on the Yakushi Buddha pedestal, I propose that the surviving work is either a copy of the earlier Buddha pedestal made in Fujiwarakyō or newly designed for the Nara temple altar using motifs and symbols of a worldscape, a “cosmos” of rule and good that commemorates the patrons of the Fujiwarakyō temple, Tenmu and Jitō. These parallel possibilities resonate with political viewpoints expressed in eighth-century historical chronicles such as Nihon shoki (compiled in 720) in terms of Tenmu’s role in the formation of an imperial-style state.

The sutra dedicated to the Buddha of Healing makes twelve great

vows to aid sentient beings. Critical to my hypotheses is the power

of the vows of the Healing Buddha expressed through the pedestal imagery, especially with regard to how the agents of that healing are depicted or imagined. The most striking motif is twelve figures in bronze relief seated 4-2-4-2 within arched niches on the sides. The twelve are depicted in loincloths, some with fangs, all with curly hair and—most significantly—generalized physiognomic features used in Tang Chinese representations of dark-skinned foreigners (kunlun) from the South Seas; they were foreign workers, slaves, or individuals who delivered tribute to the imperial authority. They were also feared and thus became a visual trope in Buddhist imagery for converted beings.

In the sutra on the Healing Buddha, lesser beings called yaksa (Japanese yasha) are named alongside other evil beings who are ultimately converted upon hearing the name of the Healing Buddha. In this state, as the “Twelve Generals,” they carry out the twelve great vows of the Buddha. The twelve on the pedestal are archetypal yaks·a depicted in the manner of foreign kunlun. Arranged beneath the sublime, seated Buddha in niches and flanking a stout hybrid human-animal god of another creed that literally supports the seated Buddha with an upheld jeweled pillar, the twelve are converted evil forces beneath a powerful good. The figures project submissiveness and charm despite their evil (foreign) guise, while their gazes and gestures engage the viewer.