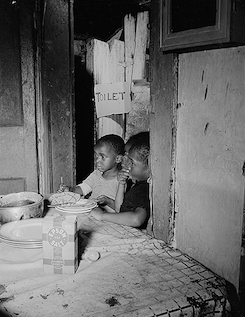

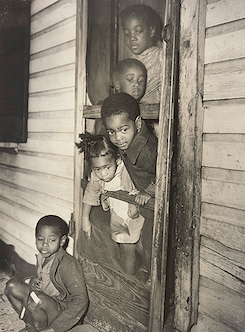

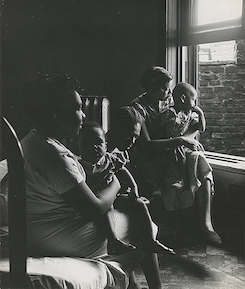

How does Gordon Parks use photography to address inequities in the United States?

How do Gordon Parks’s images capture the intersections of art, race, class, and politics across the United States?

What do photographs in general—and Gordon Parks’s photographs more specifically—tell us about the American Dream?

“A photographer can be a storyteller. Images of experience captured on film, when put together like words, can weave tales of feeling and emotion as bold as literature.… [Photographers] bring together fact and fiction, experience, imagination, and feelings in a visual dialogue that has enormous impact on how we observe and relate to the external world and our internal selves.” —Philip Brookman, “Unlocked Doors: Gordon Parks at the Crossroads,” Gordon Parks: Half Past Autumn, 1997

What did you picture while reading this quote? Consider where you encounter photographs and images in your own life. What impact do they have on you?

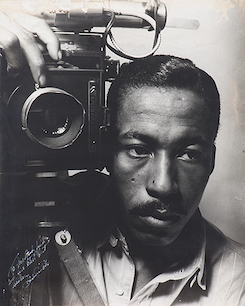

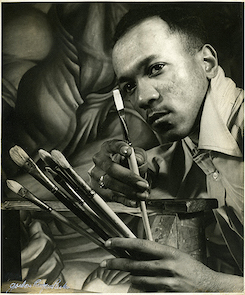

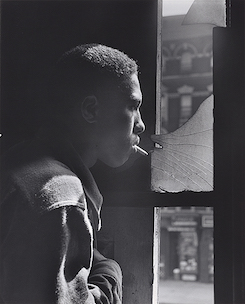

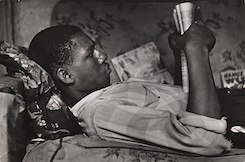

There is perhaps no individual who embodies the power of photography more than Gordon Parks. Photographer, poet, musician, storyteller, activist—Gordon Parks shaped the times in which he lived as much as he was shaped by them. Though his career as a photographer spanned six decades, it is the period from 1940 to 1950, the focus of the exhibition Gordon Parks: The New Tide, Early Work 1940–1950, that most significantly defined his point of view as an African American artist and documenter of American life at the dawn of the modern civil rights movement.