Does art “work” or have a purpose? How?

Is making art a form of work? Make your argument for why or why not.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt stated that art in America has never been the sole province of a select group or class of people. Do you agree or disagree?

Define what you think Roosevelt meant by “the democratic spirit.” How do you think art can represent democratic values?

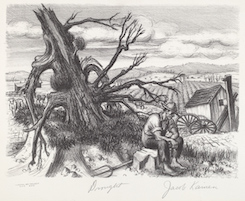

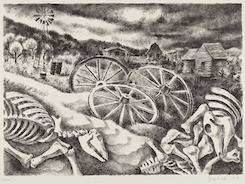

The Great Depression spanned the years 1929 to about 1939, a period of economic crisis in the United States and around the world. High stock prices out of sync with production and consumer demand for goods caused a market bubble that burst on October 24, 1929, the famous “Black Thursday” stock market crash. The severity of the market contraction affected Americans across the country. The most visible effects included widespread unemployment, homelessness, and a marked decrease in Americans’ standard of living. In addition, a severe drought produced the Dust Bowl—a series of damaging dust storms. This environmental disaster ruined many farmers during a period when the economy was largely agricultural.

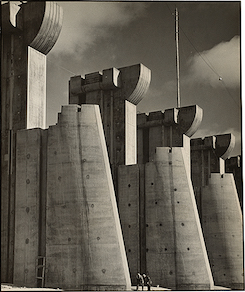

In office at the time of the crash, President Herbert Hoover (term 1929–1933) was unable to stop the free fall of the American economy. His successor, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, was elected president in a landslide in 1933 with campaign promises to fix the economy. Roosevelt acted quickly to create jobs and stimulate the economy through the creation of what he called “a New Deal for the forgotten man”—a program for people without resources to support themselves or their families. The New Deal was formalized as the federal Works Progress Administration (WPA), an umbrella agency for the many programs created to help Americans during the Depression, including infrastructure projects, jobs programs, and social services.

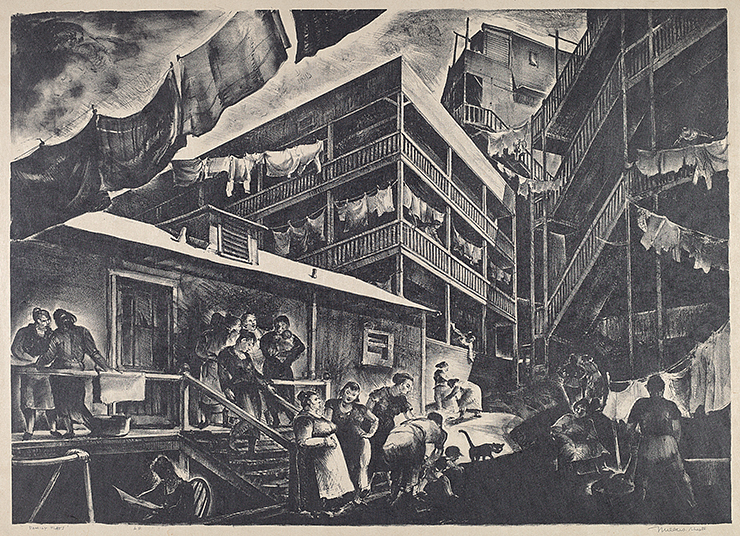

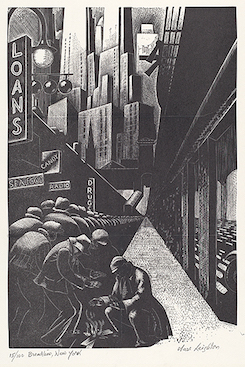

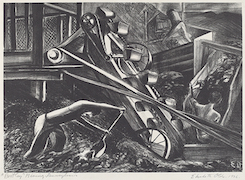

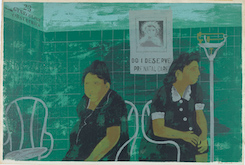

Through the WPA, artists also participated in government employment programs in every state and county in the nation. In 1935, Roosevelt created the Federal Art Project (FAP) as the agency that would administer artist employment projects, federal art commissions, and community art centers. Roosevelt saw the arts and access to them as fundamental to American life and democracy. He believed the arts fostered resilience and pride in American culture and history. The art created under the WPA offers a unique snapshot of the country, its people, and art practices of the period. There were no government-mandated requirements about the subject of the art or its style. The expectation was that the art would relate to the times, reflect the place in which it was created, and be accessible to a broad public.

Artists working in the FAP and for other WPA agencies created prints, easel paintings, drawings, and photographs. Public murals were painted for display in post offices, schools, airports, housing developments, and other government buildings. Community art centers hosted exhibitions of work made by artists employed in government programs and offered hands-on workshops, led by artists, for everyone. Illustrators made detailed drawings that cataloged the physical culture and artifacts of American daily life—clothing, tools, household items. The WPA intentionally seeded arts programs and supported artists outside of urban centers. In so doing, it introduced the arts to a much more diverse swath of Americans, many of whom had previously never seen an original painting or work of art, had not met a professional artist, nor experimented with art making.