In what ways was the US settled and unsettled in the 19th century?

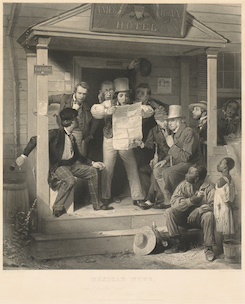

What role did artists play in shaping public understandings of the US West?

When you think about the US West, what images and stories come to mind?

A wagon train of settlers; expansive, empty lands; evidence of the concept of “progress”—these elements appear again and again in works of art and other media in the 19th century. Together these elements illustrate the idea of manifest destiny, a belief (held by some) that expansion of the US westward toward the Pacific Ocean was destined and justified. Across the Continent helped perpetuate this narrative among people who purchased and saw the print. Westward expansion was not inevitable, though, nor was it necessarily easy or pleasant for those who were impacted by the country’s rapid growth.

The United States paid $15 million to France in 1803 for lands that doubled the size of the country in what many have called the “real estate deal of the century,” the Louisiana Purchase. Yet France, and Spain before it, did not have actual legal rights to the land other than claims they asserted through colonial conquest. By purchasing rights to the territory of Louisiana—stretching from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains—from France, the United States averted fights with the Spanish or French, but precipitated conflict with the hundreds of Native nations who lived in those lands.