Isolated by its rugged, mountainous terrain, Spain relied on foreign contacts to keep abreast of the most recent artistic developments. Although compositions and techniques might derive from Netherlandish or Italian sources, Spanish art retained an emotional intensity and religious fervor all its own.

The earliest Spanish paintings in the National Gallery belong to the era of Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile, whose marriage united the kingdom. Netherlandish art exerted a pervasive influence, as can be seen in The Marriage at Cana and Christ among the Doctors by an anonymous artist known as the Master of the Catholic Kings. The heraldic devices displayed in these biblical scenes most probably refer to the marriages in 1496 and 1497 of the Spanish monarch’s son and daughter (Juan and Juana of Castile) to the son and daughter (Philip the Fair and Margaret of Austria) of Maximilian I of Austria, thus forming an alliance with the Habsburgs.

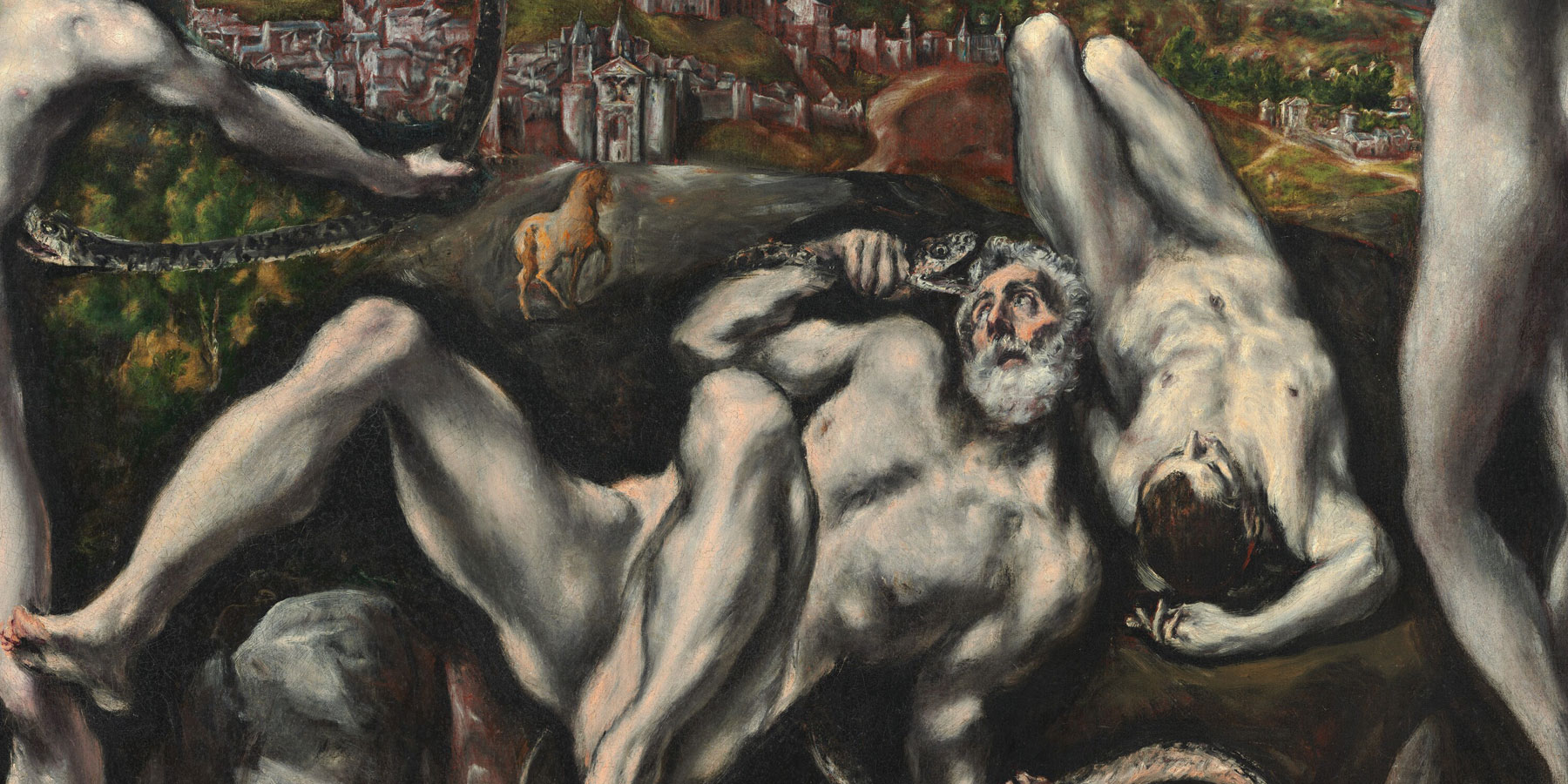

Spain’s preoccupation with spiritual matters remained largely undiluted by the new humanistic ideas of the Italian Renaissance. In the wake of the religious division caused by the 16th-century Protestant Reformation, the Catholic Church initiated the Counter-Reformation, setting strict guidelines for artists, which required that they express the church’s dogma vividly in order to stir emotions and encourage piety and devotion. Born in Greece and shaped by years spent in Venice and Rome, El Greco employed flickering brushwork and elongated figures, derived from Italian mannerism, to form an emotional, idiosyncratic style that meshed perfectly with the intensity of Spanish spirituality. This can be seen in such radiant paintings as the Madonna and Child with Saint Martina and Saint Agnes.

The 17th century’s interest in the material world fostered a new realism in painting and saw the introduction of a variety of secular subjects. Juan van der Hamen y León specialized in still life, and his Still Life with Sweets and Pottery depicts with succulent realism the sugary confections beloved by upper-class Spaniards. Bartolomé Esteban Murillo’s gifts as a storyteller are abundantly evident in The Return on the Prodigal Son, while his dramatic, theatrical style is in sharp contrast to the severe intensity of his near contemporary Francesco de Zurbarán, as seen in his Saint Lucy.

In the 18th century the Bourbons succeeded the Habsburgs on the Spanish throne. The royal family often commissioned foreign artists to decorate their palaces, among them Corrado Giaquinto and Giovanni Battista Tiepolo. Luis Meléndez was the greatest Spanish still-life artist of the century, although during his lifetime he did not gain much recognition or sustained royal support. His paintings render everyday objects with brilliant detail, marvelous effects of color and light, and subtle variations in texture. The most remarkable Spanish artist of this era was Francisco de Goya. In his early works, such as The Marquesa de Pontejos, the high-keyed pastel colors are in keeping with 18th-century taste while the shimmering brushwork owes much to the virtuoso example of his 17th-century predecessor Diego Velásquez. Goya was renowned as a portraitist, and even in his depictions of royalty there is an unflinching, typically Spanish honesty. The portraits of Bartolomé Sureda and his wife Thérèse Louise de Sureda are notable both for their dramatic presentation of personality and for their painterly bravura. Later in life Goya commemorated the Spanish resistance to the French invasion and produced a series of etchings, the Disasters of War, whose sardonic imagery resonated well into the 19th century.